Becoming a doctor remains one of the most challenging career paths one can embark upon. It requires extensive and expensive schooling followed by intensive residency training. One may go into the field of medicine anticipating that all the hard work will pay off — not only financially, but also in terms of job satisfaction. Then there’s the immeasurable personal benefits of helping people and saving lives. And in terms of respect and prestige, few occupations rank as high.

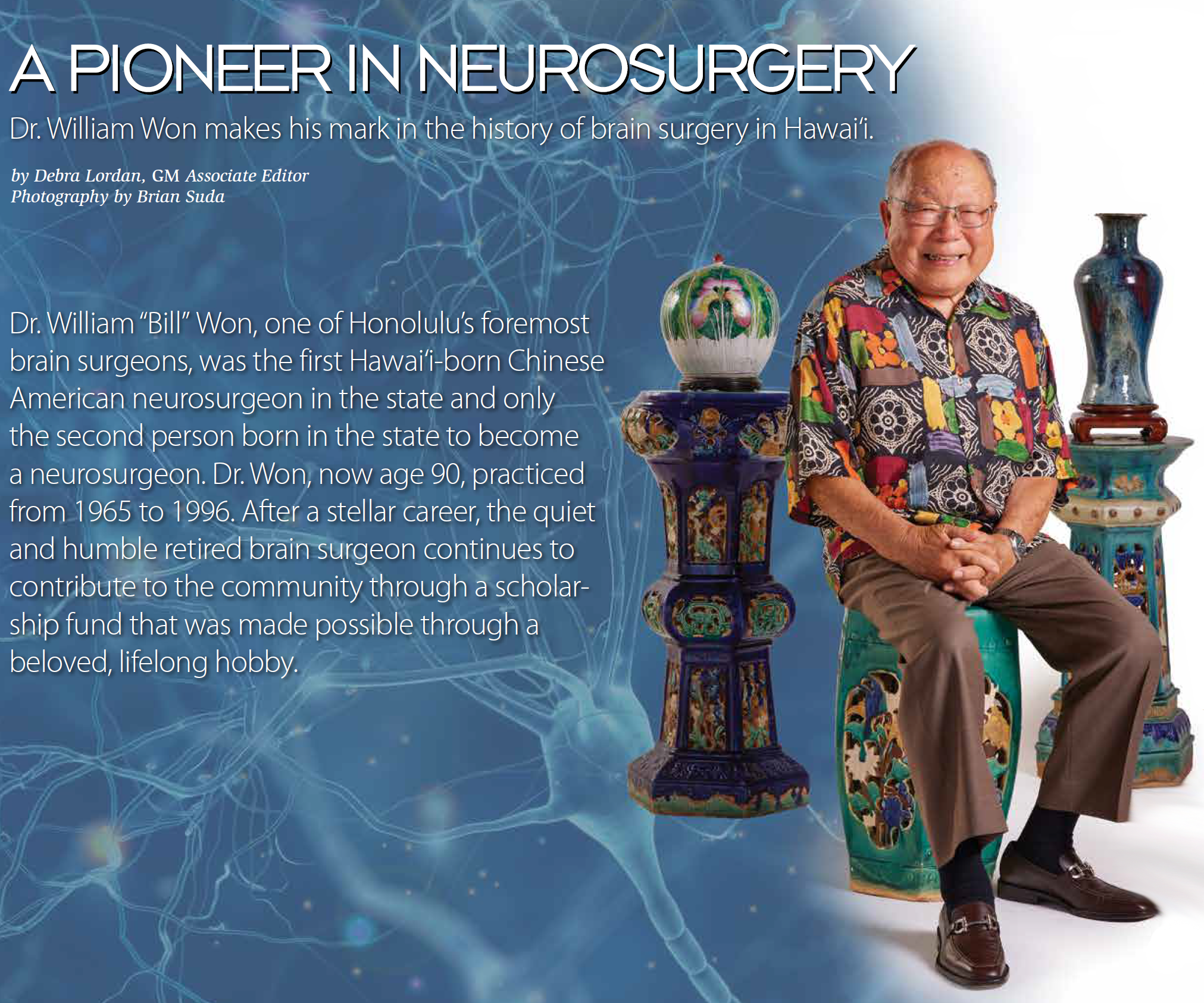

Becoming a doctor remains one of the most challenging career paths one can embark upon. It requires extensive and expensive schooling followed by intensive residency training. One may go into the field of medicine anticipating that all the hard work will pay off — not only financially, but also in terms of job satisfaction. Then there’s the immeasurable personal benefits of helping people and saving lives. And in terms of respect and prestige, few occupations rank as high.

But there are few professions that involve higher stakes or more serious responsibilities than the field of medicine. The consequences of a doctor’s decisions can be immense, leading to either remarkable or dire results — life or death. Becoming a doctor requires the discipline and determination to stay the course, and live a life true to oneself and one’s priorities.

An Ambitious Career is Born

Bill’s grandfather was part of a group of Chinese laborers who emigrated from China to California near the end of the gold rush to find a better world with greater opportunities. Since their hopes for fortune weren’t “panning out,” they headed for the Kingdom of Hawai‘i.

Bill’s parents were born here in Hawai‘i and raised their family in Kula on Maui before moving to O‘ahu. The youngest of 12 children, Bill was ambitious. Although his parents didn’t encourage him due to the Great Depression of the 1930s, he was determined to excel in the field of medicine and saw a way to become a standout by becoming a pioneer in the emerging field of neurosurgery.

Bill graduated from President Theodore Roosevelt High School in 1949, setting a course to attain his dream.

“I was always a good student,” says Dr. Won. “I had the highest grade point average in high school and also won the Harvard Prize Book as a junior. It was my ticket to Harvard, but ultimately, I chose to attend Columbia University in New York instead of Harvard in Boston.”

The Harvard Prize Book, awarded to Bill in 1948, is given to an outstanding high school student who “displays excellence in scholarship and high character, combined with achievements in other fields.” Its goal was to attract the attention of talented young students.

Although he had been given this opportunity to attend Harvard University, money for room and board would still be necessary. He had no connections or accommodations in Boston, so one of his teachers suggested Columbia. Since he had two older siblings who lived in Manhattan, he could live with them during his early college years. Other expenses that were unmet by the scholarship were covered by Dr. Won’s siblings. As the youngest, he had 11 who could help him.

He first attended the University of Hawai‘i for two years as an undergraduate, then transferred to Columbia College in Manhattan.

“I knew that neuroradiology was an emerging field but I didn’t know very much about it,” says Dr. Won. “But I wanted to make a good living as an adult. Neurosurgery was not very popular because of its long residency — seven years. Most medical residencies were three or four years after internship. Not many people went into that specialty because it was so difficult — so unknown. I had no idea just how special Neuroradiology was — but I soon found out.”

“Columbia later became the birthplace of the specialty of neuroradiology, which was non-existent at the time I started,” says Dr. Won. “Modern neuroradiology uses radiation to diagnose and treat disorders of the nervous system. But there were no X-ray scans of the brain at that time.”

After finishing his undergraduate years in 1953, he was admitted to the State University of New York Downstate College of Medicine in Brooklyn, New York, graduating in 1957.

He entered into a surgical internship at the Kings County Hospital in Brooklyn, New York, finishing in 1958. His neurosurgery residency program did not start until 1960 at the Neurological Institute of New York’s Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center, so in the interim, he was called into the US Congress’ Berry Plan military doctor draft. After completing two years of active military service in Japan as a general medical officer in the Air Force, he returned to New York City in 1960 to start his residency in neurosurgery at the Neurological Institute of the Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center in Manhattan, completing his training in 1964.

All told, he had been away from Hawai‘i for 14 years while engaged in college, medical school, internship and residency training, and active military service overseas.

He began his private neurosurgery practice in Honolulu in 1965 — one of a handful of experts in the field in the state.

The Early Days of Brain Surgery

Even a cursory outline of the history of neurosurgery in Hawai‘i would not be complete without the names of the doctors who laid its foundation here. From its humble beginnings in the early 20th century to the present day, neurosurgery has a rich and fascinating history in the state and has experienced rapid growth. This history is particularly unique, given Hawai‘i’s remote location, indigenous population and military presence. However, the information available is relatively sparse before the state’s first full time neurosurgeon settled here in the late 20th century.

The field and its limited neurosurgical care became available during this period in the form of transient traveling surgeons, notably, Dr. Frederick Reichert. Dr. Reichert trained at Johns Hopkins before moving to Stanford University, where he became chief in 1926. From California, he would make annual trips to the Hawaiian Islands to provide care for the local population.

Dr. Ralph B. Cloward, Hawai‘i’s first full-time neurosurgeon, was arguably the most influential neurosurgeon in the state. The legendary physician made extensive contributions to neurosurgical clinical knowledge, pioneering multiple surgical techniques and operative instrumentation.

Dr. Ralph B. Cloward, Hawai‘i’s first full-time neurosurgeon, was arguably the most influential neurosurgeon in the state. The legendary physician made extensive contributions to neurosurgical clinical knowledge, pioneering multiple surgical techniques and operative instrumentation.

In ’38, at age 30, Dr. Cloward began to practice neurology and neurosurgery in Hawai‘i at “the Clinic” (Straub) where his father had worked. Throughout the ’40s, he provided unique contributions to the Kalaupapa community, relieving pain and returning function to leprosy patients. During the attacks on Pearl Harbor, Dr. Cloward literally worked under fire at Tripler Army Hospital at Fort Shafter, which filled with numerous head traumas within an hour of the initial bombing.

The ’40s saw the arrival of additional neurosurgeons, including Dr. Thomas Bennet and Dr. John Lowrey. Drs. Cloward, Bennet and Lowrey worked together to provide neurosurgical care on O‘ahu for the next decade. They practiced at Queen’s Hospital, St. Francis Hospital and Children’s Hospital.

The ’50s saw continued expansion of the field in Hawai‘i. Dr. Cloward continued to practice in the ’60s and beyond, developing and subsequently refining his anterior cervical spine approach. This technique, which is used for the correction of cervical disk herniation, was ultimately termed the “Cloward Procedure,” in honor of its creator.

The Doctor Returns Home

The year of Dr. Won’s return as a neurosurgeon was the same year that the new University of Hawai‘i medical school opened its doors as the John A. Burns School of Medicine (JABSOM). Early in 1965, Dr. Won went into private neurosurgical practice and his wife went to work for Kaiser Permanente–Hawai‘i as an internist practicing primary care medicine.

“In the early ’60s, all surgeons in the state had to obtain operating privileges at each separate hospital, except for Kaiser hospital, which was a fairly new kind of health maintenance organization,” says Dr. Won. Medical insurance was in its infancy. “The Queen’s Medical Center was the most important hospital in town. Once you were accepted at Queen’s, you could work at the other hospitals — St. Francis and Kuakini Medical Center — called the Japanese Charity Hospital until Pearl Harbor was attacked. We worked at all the hospitals, but we all started at Queen’s.”

“In the mid-’60s, when I started in private practice, there were no physicians’ offices at hospitals,” says Dr. Won. “We all had to have our own

“In the mid-’60s, when I started in private practice, there were no physicians’ offices at hospitals,” says Dr. Won. “We all had to have our own

private consultation offices somewhere nearby.”

There were no trained emergency room (ER) physicians in the ’60s and early ’70s in the US. Recently graduated interns and residents mainly staffed the ERs.

Dr. Won reported that he seemed to inherit the lion’s share of pediatric neurosurgical cases in Hawai‘i at that time. However, his practice included all age groups. He performed aneurysm clippings, trauma surgery, pediatric subdural taps, placings of shunts for hydrocephalous, myelomeningocele repairs, brain tumor removals and many diagnostic tests.

CAT and MRI scans were barely even in the concept stage back in 1966.

A Challenge for Doctors and Patients Alike

Before the invention of the MRI and CAT scans, it was quite challenging to diagnose brain illnesses and injuries.

“Whenever patients with any type of head injury came in, a neurosurgeon was always called in to evaluate the injury, no matter how minor,” says Dr. Won. “Because there were no CAT or MRI scans available, we had to do specific neurological examinations and depend on what we found in physical examinations of the patient. We had to rely upon our own clinical physical exam and neurological exams that we learned to do in medical school. We had to work from scratch, because at that time, they couldn’t see through the skull. They could just take plain X-rays that only showed the outside of the skull. It was very difficult.”

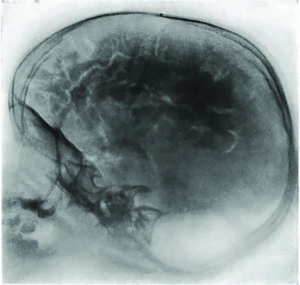

“Much of our training and residencies were spent performing diagnostic exams to find out what the problem was,” says Dr. Won. “We had to do a lot of spinal taps. In order to do a really thorough test, we drained all of the spinal fluid out of the body and replaced it with air. Air shows up on an X-ray as black, so it outlined the brain and it’s convolutions — the grooves (sulci) and the folds (gyri). The pneumoencephalogram procedure gave patients a pretty bad headache.

“Much of our training and residencies were spent performing diagnostic exams to find out what the problem was,” says Dr. Won. “We had to do a lot of spinal taps. In order to do a really thorough test, we drained all of the spinal fluid out of the body and replaced it with air. Air shows up on an X-ray as black, so it outlined the brain and it’s convolutions — the grooves (sulci) and the folds (gyri). The pneumoencephalogram procedure gave patients a pretty bad headache.

Having been trained at the Neurological Institute in New York, Dr. Won was accustomed to the use of the pneumoencephalogram chair, which could invert the patient upside down.

“Air rises, so if you wanted an image of the bottom of the brain, you had to turn the patient upside down,” says Dr. Won.

It was Dr. Won who brought the chair idea to Hawai‘i. “I was able to get the biomedical staff in St. Francis Hospital’s radiology department to build a rotating pneumoencephalogram chair adapted from an actual dental chair,” says Dr. Won. His chair was equipped to safely turn the patient upside down. “I was the only one who was able to use the chair due to my experience at Columbia. And it was quite useful, especially when doing that diagnostic test in the pediatric age group under general anesthesia.”

This was one of the best ways to study the internal anatomy of the brain and detect lesions of the nervous system before CAT and MRI scanning became available. Dr. Won’s chair was the only such device in Hawai‘i at the time.

“The chair was always in use because that was the only way to see inside the brain,” says Dr. Won. Neurosurgical residents conducted all the X-ray tests because there was no neuroradiology specialty at that time. (The angiogram or arteriogram — injecting dye into an artery — was another way of imaging the brain.)

But Dr. Won didn’t have to use the pneumoencephalogram chair very long, because the CAT scan was developed a few years later, which made diagnosis easier “and the chair immediately obsolete” adds Dr. Won. “And all the tests that we were trained to perform were eliminated.”

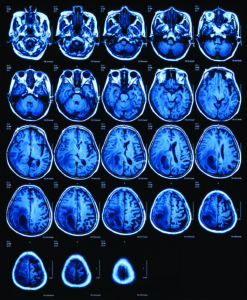

Computerized axial tomography (CAT, CT) uses a combination of X-rays and computer technology to provide comprehensive images that help detect a number of neurological conditions. The MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan, which came later, was able to reveal even more than a CAT scan could. MRI scanning, using radio waves and a strong magnetic field to provide very clear images without ionizing radiation, is best for diagnosing and monitoring many neurological conditions affecting the brain.

A Day in the Life of a Brain Surgeon

A Day in the Life of a Brain Surgeon

“Neck and back surgery was also a large part of neurosurgery practice,” says Dr. Won. “Anterior cervical fusion for cervical spine injuries and cervical disc degenerative disease was a ‘popular’ operation. Lumbar spine surgery was also more common during those days

than it is now.”

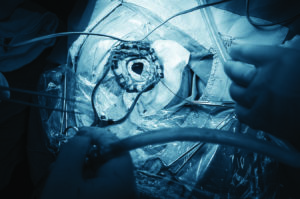

Most major procedures were craniotomies for brain tumors, aneurysms and severe brain trauma — especially posterior fossa craniectomies — a surgical procedure to make an opening in the back of the head to gain access to the brain. Special head frames with bone pins were used.

“Head trauma made up the bulk of my neurosurgery work in those early days,” says Dr. Won. “I worked 24/7, until the hospitals began to staff ERs with specialists who were fully trained MDs. Also, the availability of CAT and MRI scans replaced the necessity of having to do emergency carotid angiograms in the middle of the night. That was a great relief!”

“I did much of the pediatric work, for example, subdural punctures via anterior fontanelle, ventriculoperitoneal shunts for hydrocephalus; repair of myelomeningoceles; and rarely, posterior fossa tumors. With the now current knowledge of the important role of folic acid in the prenatal period, the occurrence of many of these pediatric abnormalities has subsided.”

“I did much of the pediatric work, for example, subdural punctures via anterior fontanelle, ventriculoperitoneal shunts for hydrocephalus; repair of myelomeningoceles; and rarely, posterior fossa tumors. With the now current knowledge of the important role of folic acid in the prenatal period, the occurrence of many of these pediatric abnormalities has subsided.”

In the late ’80s, Dr. Won moved from his St. Francis Hospital campus office to Queen’s, where he practiced until he retired.

Neuroradiology: The Evolution of Brain Surgery

Neurosurgery was still in a relatively primitive state in the ’60s and early ’70s, until the CAT scan became clinically available.

The first CAT scan machine was installed at Queen’s in the mid-’70s. It radically changed all of neurosurgical practice and firmly established the specialty of neuroradiology.

“The surgical microscope for neurosurgery was not available at St. Francis Hospital, where I did the major portion of my hospital practice in the early ’60s,” says Dr. Won. “It was not until the ’70s that we were able to get some training for its use in treating aneurysms and skull base tumors. Individual neurosurgeons in private practice had to get special training in new procedures while attending our annual American Association of Neurological Surgeons and the Congress of Neurological Surgeons meetings on the mainland.”

“In cases of extremely rare tumors or arteriovenous malformations, and in skull base and midline tumors, I would refer patients to the major medical centers on the mainland or to my neurosurgery training program in New York.”

In 1981, Dr. Won became a reluctant expert witness in an infamous court case that became a major media sensation. A circuit court judge was the target of a large public protest and was criticized by state officials when he overturned a 1979 jury verdict that found a drug dealer guilty of killing and then dismembering another drug dealer, saying discrepancies in testimony by key prosecution witnesses raised serious doubts. The judge said the jury was wrong and the verdict was wrong.

Many attorneys thought the judge was correct, according to Dr. Won.

The following day, the judge was found semiconscious from a head injury. Police said he had tried to commit suicide by falling or jumping off a table.

Although Dr. Won hoped not to be involved, the case came to St. Francis Hospital where he worked because the facility had the new CAT scanner. A CAT scan revealed bilateral skull fractures and a subdural hematoma. Bilateral skull fractures usually occur from two direct impact sites. The eyes and neck were also bruised and one of his collarbones was broken.

“If you fall down on one side, it will only fracture one side of the head, because of the big suture in the middle of the skull (fibrous tissue connects the bones of the skull),” says Dr. Won. “A fall on one side won’t affect the other side. But the judge had a fracture on both sides of his skull, so he couldn’t have just fallen. It was my opinion that the patient received several blows to the head while he was asleep.”

Dr. Won performed emergency lifesaving surgery on the judge and was called to testify in court regarding his opinion of the cause of the judge’s suspicious head injury. “But the police department was not interested in my opinion regarding the judge’s head injuries,” he recalls.

The court case gave Dr. Won much more than 15-minutes of fame — including articles in The New York Times. “It was a very sensational case.”

Current State of Neurosurgery in Hawai‘i

Current State of Neurosurgery in Hawai‘i

A hundred years ago, the only way to positively diagnose many neurological disorders was through an autopsy. Today, modern medical imaging has allowed physicians and scientists to see the structure of the brain and changes in brain activity as they occur. Some of the most significant improvements in imaging have occurred over the past 20 years, providing sharper images and more detailed functional information.

Using X-ray, MRI and CAT technologies, radiology has become an important part of the diagnostic process within neuroscience. Modern neuroradiologists focus on interpreting scans of the central nervous system, which includes the brain, spine and spinal cord, face and neck, and peripheral nerves.

Neurosurgery has continued to develop in Hawai‘i. JABSOM has a Division of Neurosurgery consisting of seven clinical faculty. The faculty operate at hospitals throughout Hawai‘i and the Pacific, including Queen’s and Straub. The faculty teach residents in the general surgery and orthopedic surgery residency programs, as well as medical students. Several from the latter group have gone on to neurosurgical residencies.

There are typically 13 to 14 neurosurgeons at any given time based at nine hospitals in Hawai‘i. The majority of neurosurgical care is provided in Honolulu. However, neurosurgical services have also been available on Maui for the past several years. The most complex procedures are performed at Queen’s, which has been home to a neuroscience institute since 1996, participating in numerous clinical trials and research projects.

Neurosurgeons are able to function with relative independence from mainland institutions. However, collaborations do exist. A recent partnership between Queen’s and the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Texas has sought to expand the scope and quality of care available in the Pacific.

Neurosurgery has continued to grow at UH and its associated training sites, making the state one of the Pacific’s premier destinations for such services.

Nurturing a New Generation

Dr. Won’s interest in collecting Chinese antiquities began during his college and medical school days. He is a longtime member of the Society of Asian Art of Hawai‘i. During his free time at neurosurgical conferences, he visited antique shops. Over the years, he acquired a collection of Chinese antiques, which he later auctioned off. That auction was an important milestone for the Wons, enabling them to create a financial aid fund for Punahou students in need of tuition assistance.

“We know the importance of education,” said Dr. Won. “Now we can offer some help to others.”

Punahou has served as a pillar in the Won family foundation since their only son started kindergarten there more than 40 years ago. He graduated in 1984; all of his children also attended. “We come from humble beginnings,” said Dr. Margaret Lai, Dr. Won’s wife, “and we realize a lot of people need financial aid, so it’s wonderful to be able to offer that.”

After he retired in 1996, Dr. Won continued to serve as the physician member of Hawai‘i’s Medical Claims Conciliation Panel (MCCP) — now known as the Medical Inquiry and Conciliation Panel.

In 2006, the Won’s son and his wife and two daughters moved back to live with them.

“Because they are busy working parents — our son is a professor of accounting at the UH Department of Business and our daughter-in-law is a professor of geriatrics at JABSOM — we were very busy grandparenting,” say the Wons.

Up to a few years ago, “Yeh-Yeh,” as his grandchildren call him, was on the Punahou campus daily, providing afternoon chauffeuring, picking them up and delivering them to a variety of afterschool activities. Margaret — “Nai-Nai” — cooked dinner for their extended family of eight, then six, when both granddaughters left for college. Now, their son and daughter-in-law have taken charge of nearly all of these activities.

After retirement, Bill and Margaret helped make deliveries for Hawai‘i Meals on Wheels for over 15 years. The Wons also attend Kaimuki Christian Church and Bible studies, and contribute to Christian organizations and missionary doctors. They enjoy gardening. and meals with friends and family, and enjoy a regular walking routine.

“We give glory and thanks to God for all His blessings,” they say.

Just Listen…

Dr. Won and Dr. Lai offer this simple guidance for future and current doctors: “Really listen to your patients and their families. Their descriptions of symptoms are an invaluable tool. When you listen carefully, patients know you care.”

_______________________________

History of Hawaii Neurosurgery, Robinson M.D., Bernard (www.amazon.com)

SOURCES

Columbia Neurosurgery History:

https://www.neurosurgery.columbia.edu

The Development of Neurosurgery in the State of Hawaii: 2021meeting.cns.org

Swinney C, Obana W, The History of Neurosurgery in the Hawaiian Islands, World Neurosurgery (2017), doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.10.065:

https://iranarze.ir/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/E9610-IranArze.pdf

WHAT IS NEURORADIOLOGY:

https://www.radiology.ca/article/what-neuroradiology

Leave a Reply