Before retiring in 2010, Moon—an attorney for 16 years and judge for 28— put the “law of the land” to work for more than 40 years. As judge, he says he was proud to support the interests of his state and country, and witness hundreds of citizens perform their civic duty as jury members within the court system. He notes that jury duty is one of the key ways citizens can engage in civics and participate in the democracy of which we all depend on.

As this issue of Generations coincides with the Fourth of July, we sat down with Moon and asked him to reflect on what it means to be an American — as a retired chief justice, Korean-American and private citizen.

From the Plantation to the Judiciary

As a third generation Korean-American, Moon doesn’t take our democracy, freedom or rights for granted.

Moon’s grandparents on both sides came to Hawai’i in the first wave of Korean immigration, between 1903 and 1905. The family lived in Wahiawa. After leaving the plantation, Moon’s paternal grandfather opened a tailor shop in Wahiawa that served as the family business for two generations. The Moon family (parents Duke and Mary, Moon and his three younger siblings) lived above the store.

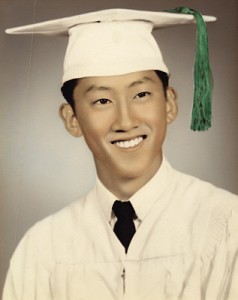

Academics were impressed upon Moon by his parents (his father wasn’t educated beyond high school due to lack of finances; his mother attended vocational business school), who believed that education was necessary if one was to be productive in life. Yet, Moon admits that he wasn’t the best student. He attended Leilehua High School and town high schools. He says that it wasn’t until he was admitted to Mid-Pacific Institute (MPI) that his parents’ advice sunk in.

“The school gave me the guidance, supervision and motivation that I needed,” Moon says. “It was difficult for my teachers and counselors, specifically the Dean of Boys and my American History teacher, Lester Cingcade.” Cingcade was instrumental in seeing that Moon, “Stop being a kid and grow up!”

At MPI in the late ‘50s, during Moon’s junior and senior years, there were “rules upon rules” for which any violation of them would result in a “charge” that would send students to the Senate Court (school’s student court). Cingcade was the advisor and honor students were the judges.

During Moon’s first year at MPI, he was in Senate Court on nearly a weekly basis for violating rules, ranging from disrupting class and holding a girl’s hand on campus to his hair touching his ears and dust on his dorm room’s window sill, etc. Punishment included “hard labor” such as pulling weeds, collecting garbage from the cafeterias, or not being able to go home on weekends.

“I believe that being a defendant in Senate Court convinced me that I would very much appreciate one day being on the “other side” of the courtroom,” Moon says.

In fact, in his senior year at MPI, Moon got the opportunity to “defend” one of his good friends. Moon explains that his classmate got caught plagiarizing. Instead of writing a report on the American classic, Moby Dick, he used the comic book edition. The senior English instructor recommended to the school that he be expelled. “This meant that after four years of attending MPI and living away from home, my friend wouldn’t graduate,” Moon says. “I knew that his parents — a schoolteacher and service station owner — were not wealthy people. Private schools are so competitive and they sacrificed to pay for their son’s way through boarding school. It didn’t seem right that he’d be kicked out in our senior year.”

With Cingcade’s voice drumming in his head “to stop being a kid and to grow up,” Moon decided to secretly visit the teacher and make a case on his friend’s behalf. As a result, Moon’s friend was allowed to stay on campus and graduate. (Later, he became a very successful businessman, and he and Moon are still very good friends to this day.)

“That experience gave me an awareness that I enjoyed helping people,” Moon recalls.

College Conundrum

Although Moon started to find focus at MPI, he didn’t graduate with college ambitions. Rather, he attempted to persuade his father to allow him to take care of the family business. “My father, however, wasn’t going to have anything to do with me unless I went to college. If I was going to skip college, then he wanted me out of the house and living on my own … I was not to rely on the mom-and-pop shop. It was just that way,” Moon recalls.

To determine Moon’s future, the family visited the well-connected and educated reverend at the Wahiawa Korean Christian Church, where they were very involved in the parish activities.

“If you had a question, it was customary to visit the reverend for guidance,” Moon explains. “The reverend stated that I would go to Iowa, as he knew of a very good school [University of Dubuque] that has a seminary … and that I was going to be a good minister one day.”

Moon attended the University of Dubuque and then transferred to Coe College, where he studied toward becoming a social worker.

A older cousin, James Choi, who was studying at the University of Iowa Law School encouraged Moon to submit his application.

“He advised me that in order to get a good job in social work, I’d probably need to earn a doctorate degree. He suggested that I try to become a lawyer … that way, as a social worker, I could understand the law and better help people,” Moon says.

In 1965 Moon graduated from the University of Iowa Law School and obtained his doctorate of jurisprudence.

After school, Moon returned to Honolulu. “It was the right thing to do to come home in ’65. At the time, memories of the war with Japan and the Korean War were still fresh in America’s mind. I didn’t feel very comfortable in a nearly all-White community. If you looked Asian, you reminded them of the enemy.”

Once Moon returned to the Islands, he became law clerk to United States District Court Judge Martin Pence. He served under Pence for one year.

In 1966, he joined the staff of the Prosecuting Attorney of Honolulu where he was deputy prosecutor. Later, Moon left public service to become a partner in the law firm of Libkuman, Ventura, Moon and Ayabe until Gov. George Ariyoshi appointed him to the Hawai’i State Judiciary as a circuit court judge.

Then, Gov. John Waihe‘e elevated Moon to the office of Associate Justice of the Hawai’i State Supreme Court in 1990. In 1993, Moon was promoted to chief justice.

No Injustice in Judgment

Judge Pence, from the U.S. District Court, had a great influence on the development of Moon’s judging philosophy that revolved around two key points — judicial independence and treating all who appeared before the judge with respect.

“Pence essentially taught me judging,” Moon says. He educated Moon on how to review cases and how to remain objective despite outside pressures, such as the media, politicians, big-business, special interest groups, and even protests outside of the courthouse.

“Pence insisted that judging always comes down to the facts of the case from evidence only admitted in court. Once determining the facts, you then apply the applicable law to those facts,” Moon says. “You don’t let the outside influence your decisions. That is what judicial independence is all about. That’s what I tried to do throughout my career.”

Moon continues to promote judicial independence in Hawai’i, and is averse to the fact that judges in many other states are elected rather than selected under a system like Hawaii’s that utilizes citizens and lawyers in the selection process. “When judges are elected — and they need to waves signs, ask for donations, gain votes — they become politicians,” he says.

To get votes, you have to be popular, Moon notes. “When a big issue comes up and you make a ruling … and it’s not a popular decision … You lose votes and perhaps lose your job. Judges can’t be placed in that kind of situation.”

Moon’s second guiding principle — to treat people with respect, courtesy and civility — stems from the overarching ideologies of his father, Cingcade and Pence.

“I told the judges who I supervised that they should not scold, admonish or belittle people, like ‘Judge Judy’ on TV,” Moon says. “They shouldn’t exhibit condescending behavior toward the people that come before them.”

Democracy On Trial

After spending four decades in the legal system, Moon has witnessed the pros and cons of the legal system. One of the greatest weaknesses, he fears, is our lack of civic knowledge. And he questions whether it poses a threat to American democracy.

“The kind of ignorance that I’m talking about is illiteracy in civics — understanding government, its makeup and how it works … being able to name the vice president, your state’s senators or the three branches of government — executive, legislative, judiciary,” Moon explains. “Our inability to do so disappoints me a great deal.”

Moon sites a recent study by the Center for the Study of the American Dream at Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio, which reveals that one-third of native-born citizens fail the civics portion of the naturalization test, in stark contrast to the 97.5 percent pass rate among immigrants applying for citizenship.

“Some people may argue that immigrants had time to study,” Moon says, “but I contend that native-born citizens have lived here all their lives, spend 12 to 18 years in school, have access to unlimited media and resources … yet they can’t name the governor of their own state or identify the law of the land, such as The Constitution? It’s just amazing and depressing!”

Moon explains, “It’s because of these kinds of reports year after year when I was serving in the judiciary, especially as a chief justice, that I understood clearly why nearly 25 percent of people don’t show up for jury duty in Hawai’i (and up to 75 percent in other states such as Florida), and why voting is at an all-time low. People are oblivious to their civic responsibilities.”

Our country is like a family: Everyone has to pitch in or it doesn’t work. As citizens of the American “family,” we all have certain responsibilities, like going to school, voting, obeying the law… and jury duty.

Any jury pool assembled to try a criminal or a civil case is supposed to be drawn from all socioeconomic classes of the general population. When a quarter or more of the people summoned don’t show up, the person who is in trial is potentially robbed of the opportunity to be fairly judged by his/her peers.

Moon explains that he understands that jury duty is not an attractive thing to most people. In fact, he’s heard “every excuse in the book” to get out of it. Moon says, “But I always ask people who try to skip jury duty to imagine a situation where their friend, family member, spouse, or themselves is charged with a crime and a jury trial is set to determine their guilt or innocence. Wouldn’t they want a good, fair and well-balanced jury? Wouldn’t they want a peer to represent them in the jury? Would they want a reluctant jury member who doesn’t want to give service — or doesn’t believe in the jury system — sitting in judgement of them?”

Use Your Voting Voice

“Civic literacy is important so everyone can understand democracy and see how things are done in government,” Moon says.

Moon points out that the first general election in 1960 after Hawai’i became a state, voter turnout was 94.6 percent. Since then, the rate has been gradually slipping. In disbelief, Moon says that in 2008, “even when we had a local boy running for president, Hawai’i was last of all the states with a 43.6 percent voting rate.”

To vote is to respect the history that granted us that privilege. To vote is to help your state and country choose positive leaders. Whether or not your candidate wins, the point is that you used the voice and power that was given you.

Retiring From The Bench

After Moon’s first term as chief justice ended, he considered retiring. He knew his wife Stella would like to spend more time with him, but she also encouraged him to go for a second term — he says, “as long as I thought I’d enjoy myself.”

Moon decided to apply, and in 2003 he was retained to serve a second term as Chief Justice of the Hawai’i State Supreme Court. He retired in September 2010 — three years shy of completing the term because under Hawai’i law all judges must retire at age 70.

“I feel that for me, the age limit was very appropriate. I had 40-plus years in the legal field — nearly 18 of which were as chief justice — the longest serving chief justice since statehood. I was ready to go!”

“I’m indebted to Stella, my biological and adopted children, my parents and grandparents for the tremendous support and love they’ve extended to me in my pursuit of love, peace and joy in my career throughout the years,” he says.

Going Out On Top

To cap his career, the West O‘ahu court complex in Kapolei was named the Ronald T. Y. Moon Judiciary Complex just days before his retirement. It currently serves as the new home of family court for the 1st Judicial Circuit.

“I was very flattered and honored that it was named after me,” Moon says. He notes that his predecessor Chief Justice Herman Lum had the original idea 20 years earlier and spent a lot of time trying to convince the legislature to build a one-stop shop family court center.

“When Lum retired and I took his place, the family court was still a very good concept. Luckily at the time, Kapolei was new and the ‘second city’ was looking for community foundations, such as a courthouse,” he says.

In retirement, Moon continues his lifetime civil service by offering dispute resolutions, such as mediation and arbitration. He also aids high-risk teens in Waipahu at Kick Start Karate, founded by former Honolulu Police Chief Lee Donohue. In addition, Moon sits on several boards, including Mid-Pacific Institute, St. Louis School, Wahiawa United Church of Christ and Ohana Pacific Bank.

“I have the opportunity to learn new things and read material that isn’t strictly law… it’s so refreshing,” Moon laughs. “Retirement, which is your last phase of life… is ultimately the best. I just love it. Maybe I should have retired earlier!”

Whether working or retired, Moon encourages everyone to get involved in civics in whatever way best suits them. “I understand that everyone is busy trying to make a living, but we should all do what we can to get involved in the community — PTA, Lions or Rotary Club, team coach, tutoring and so forth,” Moon says. “We fulfill our civic duties by investing in our communities and country … thereby enjoying, strengthening and preserving our rights and freedoms.”

It was a family affair at the Kapolei Judiciary Complex ceremony and Chief Justice Ronald Moon’s retirement celebration. From left to right: Moon’s wife Stella; mother Mary; daughter Julie and sons Scott and Ronald Jr. (not pictured); and step-daughters Jan and Jill; and step-son Herb (not pictured).

Leave a Reply