The measures that came into effect in wartime Hawai‘i were described by one man who helped create them, Maj. Gen. Thomas H. Green, as “a new experiment in government — a joint operation of the military, civilian business and the general public.”

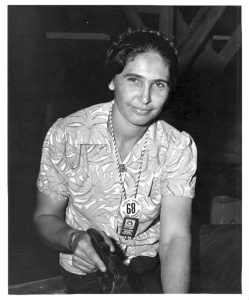

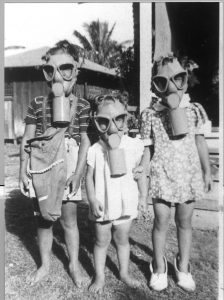

A great number of the general public were, of course, women and they played many roles on the home front. Bella Fernandez is noted as a “rated woman boat builder at the Pearl Harbor Navy Yard” on the back of a U.S. Navy photograph in the University of Hawai‘i Archives. Others did piecework at home for the armed services, some creating the camouflage netting that was put over the helmets U.S. soldiers wore, as Rosaline Ventura did. Her oral history in the UH Center for Oral History’s project “An Era of Change” also tells of day-to-day life under martial law for this mother of three young children — including toting a heavy gas mask with her wherever she went and making sure the keiki had theirs.

Many women already worked in professions that could immediately make a useful contribution to the war effort. In the immediate aftermath of the bombing, all schools were closed for a time, but teachers were reassigned to assist in registering the entire population for ID cards. For public health reasons, everyone had to be immunized against typhoid, and nurses played their part in getting that done. Office workers formed a Women’s Volunteer Army Corps, many of its members working long hours in the offices of military staff.

“Society women,” whose household and family obligations were taken care of by paid staff, volunteered for a myriad of roles. The Red Cross Motor Corps, composed of a group of about 38 women, operated a 24-hour ambulance service as part of Civil Defense. Others volunteered their time on the many committees that gave support to agencies created to deal with specific wartime needs, including the Evacuee Assignment Office.

In total, 13,000 women and children were evacuated to the mainland, most of them dependents of military personnel. Hawai‘i’s Military Governor, Lt. Gen. Delos C. Emmons, resisted any mass evacuation of civilians of Japanese ancestry believing it would be illegal and would adversely affect the war effort. The military did, however, force many families from their homes and land. In her oral history, Ruth Yamaguchi tells how their home at Pu‘uloa was commandeered to house soldiers. Her father found work at Pearl Harbor and she herself left school before graduation to work at the Hawaiian Army Exchange.

Find out more:

• Hawai‘i Goes to War, by DeSoto Brown

Has many photographs and is in your public library.

• Hawaii War Records Depository Photos (UH Archives)

• “An Era of Change: Oral Histories of Civilians in World War II in Hawaii”

• Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai’i

• Martial Law in Hawaii, by Maj. Gen. Thomas H. Green USA (Ret.)

Leave a Reply