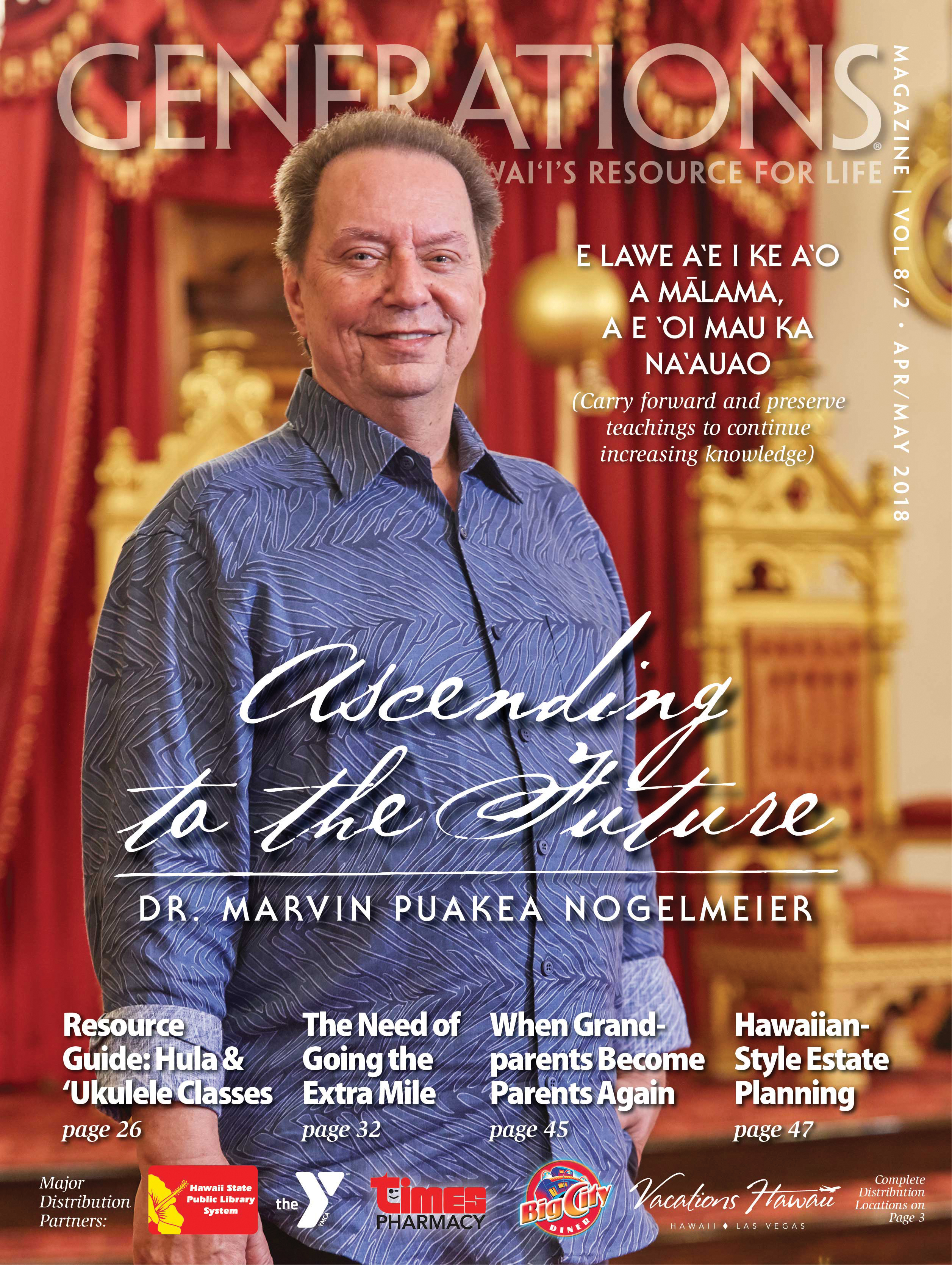

A living and vibrant culture rests on two bedrock foundations: a living language, and land that reveres places connected to the history, beliefs and hopes of its people. One of the people at the nexus of language revival in Hawai‘i is Dr. Marvin Puakea Nogelmeier, PhD, Professor of Hawaiian Language at the University of Hawai‘i, Mānoa; Po‘o/Director of The UH Institute of Hawaiian Language Research and Translation; the Director of UH Sea Grant’s Center for Integrated Science, Knowledge, and Culture; and the Executive Director of Awaiaulu. He calls himself an “unlikely” person to have become a Hawaiian cultural expert, but his works say otherwise. His life work has built mightily on the foundations that his mentors lovingly shared with him; his many students are equipped to steward the language and knowledge into the future.

Hawaiian Cultural Renaissance

By 1970, there were so few fluent speakers that the language was in danger of becoming extinct within a generation. The Hawaiian Dictionary, by Pukui and Elbert, “Hawaiian Astronomy” by Professor Rubellite Johnson, and histories by S.M. Kamakau and J.P. ʻĪʻī and others were archival reference materials. The oral tradition had been all but lost, and schools were teaching “about” the Hawaiian language.

A movement to teach children to speak Hawaiian resulted in Pūnana Leo preschools, Hawaiian Immersion Schools (K-12), and cultural reference materials like Māmaka Kaiao: A Modern Hawaiian Vocabulary, through University of Hawai‘i Press. Some of us have been fortunate to hear a kupuna mānaleo (native-speaking elder) fluently tell the story of his birthplace and recite the genealogy of his ancestors, but soon their voices will be heard only on audio tapes.

Is the revival strategy working? A couple of weeks ago, in a local restaurant, I sat next to a large table of college students celebrating a birthday. Their joyful conversation was entirely in Hawaiian, although the group was ethnically diverse. Yes, Hawaiian language is growing again! Immersion school teachers now instruct the children of their first students, who speak Hawaiian at home!

Climbing up from near extinction required bold moves by dedicated elders, linguists and teachers — with the cooperation and resolve of many students and volunteers. In 1972, 18-year-old Marvin Nogelmeier was on a walkabout trip to Japan, stopping on O‘ahu for the weekend — and 46 years later, this self-described “optimist” has built upon and freely shared the knowledge, wisdom and culture that his mentors and teachers entrusted to him. The result is the ascendancy of Hawaiian culture for all of us.

Puakea – White Flower and Fair Child

Dr. Nogelmeier is not Hawaiian, but his resonant baritone voice narrates significant documentaries about Hawaiian culture. When we ride TheBus in Honolulu, he announces every stop along the route. His fluency and clear pronunciation reach out to a broad public base, and his translation and interpretation projects are quietly moving the language renaissance to a new level.

He says that being a Haole has both disadvantage and advantage. “Sometimes I am isolated,” he says with a smile, “but with that comes a certain kind of freedom and flexibility. In a sense, I got to pick my own ‘family’ of mentors and we all get along.”

The story of his mentors and how he applied the knowledge that they shared is quite remarkable. Young Nogelmeier first found work in Wai‘anae as a goldsmith and quickly made friends among local crafters and cultural practitioners. His affinity for the arts and native curiosity led him to join Mililani Allen’s first men’s class in her hula school, Hālau Hula o Mililani.

“Hula was life-changing for me. The girls’ class was an hour long but the boys’ class lasted four to five hours. We were empty calabashes that Mililani wanted to fill with knowledge of the songs, chants and motions we performed. She opened the doorway for us to learn Hawaiian ways, including language, chant and beliefs. Mililani’s teacher, Aunty Maiki Aiu Lake, gave me one of her own names, Puakea, which means white flower and fair child,” he says.

Before long, Nogelmeier was learning to chant under the tutelage of two icons of Hawaiian Studies, Aunty Edith Kawelohea McKinzie, author of Hawaiian Genealogies and Aunty Edith Kanaka‘ole, Kumu Hula, chanter, and Nā Hōkū Hanohano award composer.

Discovering Mentorship — The Hawaiian Teaching Method

“I remember one day in the middle of chant presentation an older man came over and spoke to me in Hawaiian. When I apologized that I didn’t speak the language, he then asked, ‘You are saying the words correctly, but how do you know what you are chanting? How can you know how well you did?’

“Uncle Luka Kanaka‘ole’s compliment and question made me want to learn Hawaiian. Auntie Edith McKinzie offered to teach me and some other chant students basic language in a weekly back-porch session. Soon after, I found someone to study under. June Gutmanis, a researcher in Hawaiian culture, had Mr. Theodore Kelsey living with her, a Hawaiian speaker who helped June with her translations and interpretation of Hawaiian writings. Kelsey was born in Washington state in 1891 and his mother, hired as a teacher, brought him to Hilo in 1892. ‘Ōlelo Hawai‘i was still in common use for business, government and daily life, and as Mr. Kelsey said, ‘If you wanted to have friends, you learned to speak Hawaiian.’”

When Nogelmeier asked Mr. Kelsey to teach him Hawaiian, Kelsey replied, “No; I am not a teacher.” His main interest was to translate and interpret the “Kumu Lipo,” an expansive Hawaiian creation and genealogy chant that takes many hours to recite.

The next week at June’s house, Nogelmeier greeted Mr. Kelsey properly with, “Aloha kāua,” and Kelsey responded with some long sentences in Hawaiian.

“I didn’t get it all, but answered what I could,” says Nogelmeier. “For Hawaiians, protocol and how things are approached are as important as the message. By simply attempting to ‘talk story,’ I had demonstrated my intention to learn and opened the door to a mentoring relationship that lasted nearly a decade.”

Nogelmeier calls all his teachers “mentors,” because this one-on-one coaching method is the Hawaiian model for teaching. Learning and teaching depend on social relevancy and “chemistry” that encourage a flow of knowledge and insight. When teacher and student find one another through a shared interest or goal, the outcome is positive.

Nogelmeier attributes his deep interest and skills as a translator to Theodore Kelsey, whom he describes as a Victorian gentleman.

“He would not translate for June any passages that he considered sexual, political or vulgar, but he would go through them with me. I would then share them with June for her research. It was a working triangle that preserved the literature as it was written. Mr. Kelsey was also a fine photographer who documented Lili‘uokalani’s funeral in 1917. His love for language and history led him to dedicate his life to preserving important Hawaiian literature — documenting, translating and interpreting became his life mission,” says Nogelmeier.

Becoming a Kumu ‘Ōlelo Hawai‘i (Hawaiian Language Teacher)

In 1978, Nogelmeier was 25 years old and learning Hawaiian from one of the then-rare fluent speakers. His friends could not understand his interest in Hawaiian culture, but he pursued a degree at Leeward Community College, where he studied under Noelani Loesch. She strongly encouraged his work with Mr. Kelsey, linking it into the university classroom.

“There were so many who taught me along the way, but the discipline learned under Theodore Kelsey’s tutelage allows me to do my work today. We would spend the first hour translating a passage of chant, but many more hours researching all the places names, mythical references, connotations of words and phrases, and the personal aspects of author style and story line. For Mr. Kelsey, a complete interpretation required deep analysis.”

Puakea excelled at language and for three and a half decades, he has been teaching the Hawaiian language at the university level. Many of the Hawaiian Immersion teachers who trained under him are now training new teachers.

Unlocking the Gate to Hawaiian History

A revived Hawaiian language began to grow in the university and in charter schools throughout Hawai‘i. Words for modern developments were coined, like lolo uila (electric brain) for “computer” and leka uila (electric letter) for email. But all the Hawaiian literature written in the 1800s by authors who knew the stories of the great chiefs was difficult to access, even by Hawaiian speakers. Less than 3 percent had been translated into English, and there were only a few Hawaiian trained translators. While language teachers were fluent in modern classroom language, they had never been encouraged to develop the skills to translate old writings. And translation is a full-time job that requires intense focus.

“The other issue is that Hawaiian language we use today in the university setting is different from the language written down 150 years ago. We do not speak English the way our grandparents did. Hawaiian is the same,” says Nogelmeier.

The Hawaiian Newspaper Initiative

In 2001, the Hawaiian Newspaper Initiative was born. Although the Hawaiian language was an oral tradition before 1820, the Sandwich Isles Missionaries worked with Hawaiians to codify the Hawaiian alphabet, learned the language, and joined in teaching Hawaiians to read and write. By mid-century, Hawai‘i was one of the most literate nations on earth. Between 1834 and 1948, 100 different Hawaiian-language newspapers published over 125,000 pages, 76,000 of which were preserved, archived and indexed on microfilm. The deteriorating microfilm could not be searched by keyword. Therefore, the newspaper initiative sought to transcribe all the newspaper stories and ads into searchable Hawaiian-language digital print files. The body of literature was immense — equivalent to more than 1 million letter-sized pages of copy. The transcription process of typing each page was slow going.

In 2011, a huge public awareness campaign called “‘Ike Kū‘oko‘a: Liberating Knowledge,” recruited 7,500 volunteers in 12 countries to transcribe newspaper pages. The Office of Hawaiian Affairs also provided funds to have newspapers electronically scanned, so by the end of 2012, all the extant newspaper archives were digitized and searchable, by Hawaiian keyword. Nevertheless, only a few Hawaiian-speaking researchers were able to read and understand primary source records like these. Others were relying on poor English translations because that was all they had.

Preserving Knowledge

In 2003, while finishing his Ph.D., “Mai Pa‘a i Ka Leo,” (don’t restrict the historical voice) Nogelmeier was asked a profound question by his former student Dwayne Nakila Steele, owner of Grace Pacific Corporation: “Are we preserving language or preserving knowledge?” Obviously, the two are connected. Language expresses knowledge, and knowledge is the basis for the ideas language expresses. Nakila was really asking, “Does preserving the language do enough? Don’t we have to preserve the historical ideas and knowledge so that the modern language has a cultural foundation to rest upon?”

Puakea Nogelmeier approaches challenges in much the same way ancient Hawaiians did: Problem-solving is an intellectual sport — melding tried and true methods with creative alternatives to produce a practical outcome. He looks for simple answers, never takes his eye off the goal, and delights in the process along the way. This time, he applied Hawaiian mentoring to the problem of developing a large team of translators.

Nakila’s Dream: Awaiaulu: Hawaiian Literature Project

In 2004, Puakea and Nakila collaborated to create a stable of skilled Hawaiian translators who could, over time, confidently translate nearly all the Hawaiian newspaper body of literature.

Mentoring takes an extraordinary commitment by both mentor and student. Puakea created the program as a stand-alone nonprofit organization and began mentoring two interns, who would learn a method of translation and interpretation he distilled from Kelsey and others like Sarah Nākoa and Kamuela Kumukahi. Nakila funded the interns for two years. Candidates had excellent language skills with demonstrated work in the Hawaiian language. Their training now focused on the process of translation and interpretation of small chunks of the huge literature archive. Interns graduated to became “resource people,” qualified to both translate and also mentor more interns.

Four years ago, Kalei Kawa‘a of Moloka‘i Hawaiian Immersion School and Kamuela Yim, a teacher who is now with the DOE’s Office of Hawaiian Education, became translator trainees for Awaiaulu.

“When they tackle a story, trainees may spend one hour drafting a line-by-line translation of a selection written by Samuel Manaiakalani Kamakau, and then work four more hours smoothing and contextualizing the story,” says Nogelmeier.

Although Hawaiian vocabulary is quite precise, words may have different connotations or meanings depending on how they are used within a sentence pattern. Translation relies heavily on context. Analyzing word choice, sentence construction and references to places, nature, persons, practices and legends are critical. To add to the complexity, Hawaiians prized authors who crafted double meanings, wordplay and poetic references. Translators must explore all levels of meaning and note them for the reader. When you read a Hawaiian story, always read the editor’s notes.

“From these small beginnings we now have 18 people mentoring trainers, training translators or learning how to be a translator,” says Nogelmeier.

A Legacy of Knowledge and Language

Now, the number of translators and persons skilled at presenting newly-translated Hawaiian literature is increasing exponentially. Many famous stories about pre-contact Hawai‘i were published in Hawaiian newspapers as weekly or monthly columns. When a full story is translated, Awaiaulu publishes it as a book, available to the public. Nogelmeier’s translation of Ka Mo’olelo O Hi’iakaikapoliopele: As Told by Ho’oulumahiehie was published in 2013 and earned several literary awards. See all their publications at www.Awaiaulu.org.

The successful mentoring program at Awaialua is preserving Hawaiian literature and knowledge for our entire community.

Dr. Nogelmeier recalls the time when Mr. Kelsey, then 89 years of age, said to June Gutmanis, ‘I think Puakea will carry on my work.’”

If Samuel Kamakau, prolific author of 19th century Hawaiian nūpepa articles, were alive he might close this story this way:

Oh reader, whether you interpret the great translator’s statement as wishful thinking, a sideways request or a prophetical vision, the outcome and manifestation are clear. No more will the stories, legends and myths — nay, the stories of our great chiefs that thrilled our great-grandparents’ hearts — be hidden away. Our children will delight in the celebrations, political intrigue, dirges and simple stories of farmers and fishers who loved this ‘āina before them.

Pīpī holo ka‘ao. (So the story goes)

2018: Year of the Hawaiian

This year is a good time to read a Hawaiian story, or learn Hawaiian language. Ask your local immersion school about community adult classes, or inquire at your local senior center. It’s a fun mental exercise for brain health, and a way to learn the history and culture of the land we love.

Leave a Reply