As morning dawned on December 5, 1941, a fisherman cast his net along O‘ahu’s north shore. A college student helped his father open a new business. A volunteer took kids to the beach in Waimānalo. Two University of Hawai‘i students, watching soldiers running drills nearby, talked about war preparations while they checked out the surf. It was pretty much like most other days, for most people.

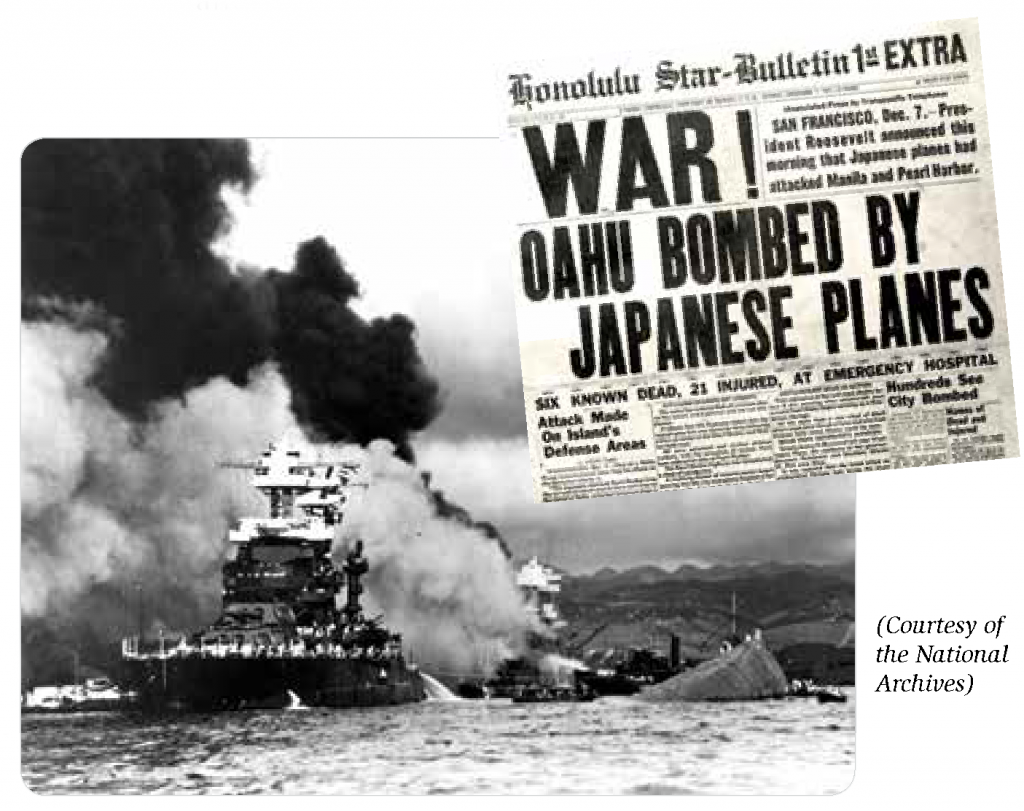

But Sunday, December 7, 1941, would become known as “a date which will live in infamy” and President Franklin D. Roosevelt would announce to the nation the next day that, early on Sunday morning, “the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan.”

The impact of that attack led to events that would change the life of every person in the U.S.— especially those living in Hawai‘i — and especially those of Japanese descent.

The bombs that dropped on Pearl Harbor exposed fears, suspicions, and distrust toward Japanese immigrants (issei) and their American-born children (nisei).

The days leading up to December 7 were idyllic for many, including Japanese American youth, most of whom had never been to Japan and whose patriotism for America ran deep.

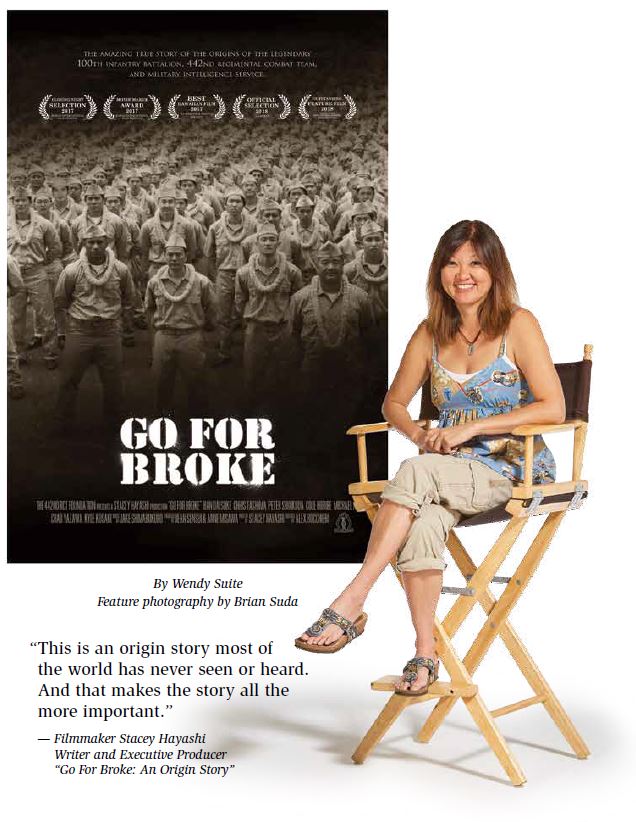

It’s against this backdrop that a new, locally produced film, “Go For Broke: An Origin Story”—written and produced by Stacey Hayashi — tells the true story of the origins of the all-Japanese American military units: the 100th Infantry

Battalion, 442nd Regimental Combat Team, and Military Intelligence Service (MIS) during World War II.

True, untold stories

Like today, most people of Japanese descent born in Hawai‘i in the early 1900s felt fully American. It was the only country they knew.

Why, then, did Japanese Americans feel a need to prove their loyalty to their country?

Why did the 442nd adopt the motto: “Go For Broke,” meaning ‘risk it all’ or ‘shoot the works’?

What compelled them to show such selfless courage on the battlefield that theirs would become the most decorated combat unit for its size and length of service in American history?

The answers to these questions can be found in the untold stories of these humble, loyal, and in many ways, ordinary Americans whose actions proved their loyalty to their country.

![Above: Varsity Victory Volunteers at work building field ice boxes in Hawai‘i. Below: VVV assembled in formal dress with gas masks. Identifiable men are Harry Sato, Yoshiyuki Hirano, Yasuhiro Fujita, James Okuda, David Fujita, Thomas Shintani, Masato Yoshimasu, Minoru Ikehara, and James Oka. [Courtesy of Ted Tsukiyama]](https://generations808.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/snapshot-25-vvv-1024x688.jpg)

The fight to fight

The first of these untold stories was the fight for the right to fight for their country. Before the nisei soldiers could display extraordinary valor against the Nazis in Europe, they faced tremendous adversity on the home front.

Few people were aware then, or even now, that 4,000 Japanese Americans were already serving in the U.S. armed forces at the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor, most of whom were in Hawai‘i, serving draft time.

Soon after the Japanese attack, Americans of Japanese Ancestry (AJAs) were reclassified 4-C: “enemy aliens,” ineligible to serve in the U.S. military — despite being U.S. citizens. AJAs already in the military were discharged and stripped of their weapons, simply because of their race.

Other AJAs, who wanted nothing more than to fight for the country of their birth, were denied that opportunity, simply because of their race.

Few people are aware that the 442nd Regimental Combat Team wasn’t organized until more than a year after the start of the war—a critical period of time when Japanese in America faced racism, discrimination, arrests by the FBI, and mass incarceration on the U.S. West Coast. Even fewer people are aware of the circumstances and actions which led to its formation—stories which form the heart of the movie “Go For Broke: An Origin Story.”

On December 7, members of the university ROTC were activated into service as the Hawai‘i Territorial Guard (HTG). They were assigned to protect ‘Iolani Palace, other government buildings, and utility and military installations — proud to serve their country and trusted to repel the impending invasion. But then the soldiers became highly discouraged when their own government called them: enemy aliens.

That’s when a little-known hero stepped into the story. A community leader and Executive Secretary of the Atherton YMCA, Hung Wai Ching empathized with the dejected college students and listened as they said they wanted to prove their loyalty to their country by fighting for it.

Ching encouraged them to volunteer their service as non-combat civilian laborers.

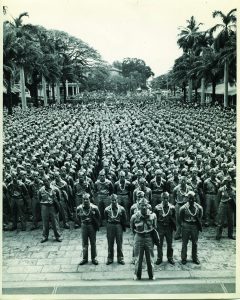

“If they don’t trust you with a gun, maybe they’ll trust you with a pick and shovel,” he said. And so began nearly a year of service for 169 university students, assisting the war effort in a military labor battalion. The former university ROTC students called themselves the Varsity Victory Volunteers (the VVV, or Triple V), and they built roads and buildings, and broke rocks — armed, not with rifles, but with picks and shovels, hammers and saws, crowbars, and sledgehammers.

In June 1942, the AJA soldiers of the 298th and 299th Infantry were segregated into the Hawai‘i Provisional Battalion, and sent out of Hawai‘i to basic training in secret. They became the 100th Infantry Battalion (Separate), an orphan unit which no one wanted, at first. But their record-breaking performance in basic training proved that AJAs would be outstanding American soldiers.

Meanwhile, at home in Hawai‘i, the dedicated and loyal VVV impressed military officials, which helped change the minds of military and political leaders — paving the way for the formation of an all-Japanese-American unit: the 442nd RCT.

The legendary 442nd RCT

In February 1943, the War Department called for 1,500 AJA recruits for the 442nd. Because of their role in effecting the creation of the 442, members of the VVV were the first to hear the news and they voted to disband so they could join the unit.

On the U.S. mainland, 1,208 recruits volunteered from inside concentration camps, where their families would remain incarcerated by President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066.

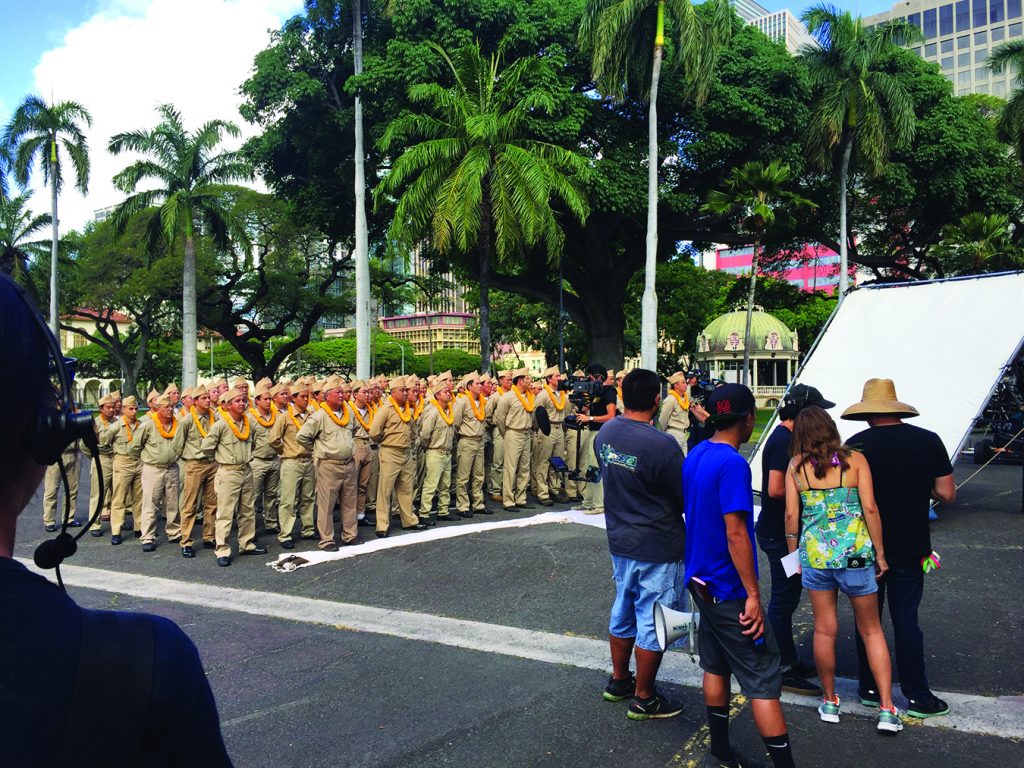

In Hawai‘i, almost 10,000 volunteered. And on March 28, 1943, 2,686 members of the newly-formed 442nd Regimental Combat Team marched down King Street, lined up at ‘Iolani Palace, and then headed off to basic training on the U.S. mainland and onward to European battlefields.

In just two years of combat, 14,000 men served in the 442nd, with a well-documented record of bravery that is unequaled to this day.

In just two years of combat, 14,000 men served in the 442nd, with a well-documented record of bravery that is unequaled to this day.

Much less is known about the vital roles and great danger faced by thousands of nisei linguists who served in the Military Intelligence Service (MIS). Their work as interpreters, interrogators, and translators was strictly classified during the war and for decades beyond.

A record of heroism and sacrifice

The 100th/442nd RCT is the most highly decorated unit in U.S. military history for its size and time in combat. Its 18,143 individual and unit decorations include: 9,486 Purple Hearts, eight Presidential Unit Citations, 21 Medals of Honor, 33 Distinguished Service Crosses, one Distinguished Service Medal, 559 Silver Stars, 22 Legion of Merit Medals, 4,000 Bronze Stars, 15 Soldier’s Medals, 12 French Croix de Guerre, two Italian Medals for Military Valor, and a great many more.

In 2010, the Congressional Gold Medal was awarded to members of the 100th/442nd and MIS. And surviving 442nd members have been honored with France’s highest and oldest award, created by Napoleon himself: “Chevalier dans l’Ordre National de la Légion d’Honneur” (Knight in the National Order of the French Legion of Honor) for their key participation in the liberation of France during WWII.

On July 15, 1946, President Harry S. Truman welcomed members of the 442nd to the White House. Acknowledging the challenges they faced at home and abroad, he said: “You fought not only the enemy but you fought prejudice, and you have won.”

A local girl needing to tell a local story

“The untold story is the adversity these young men faced, the character they showed, for the 442 to be created in the first place.”

— Stacey Hayashi

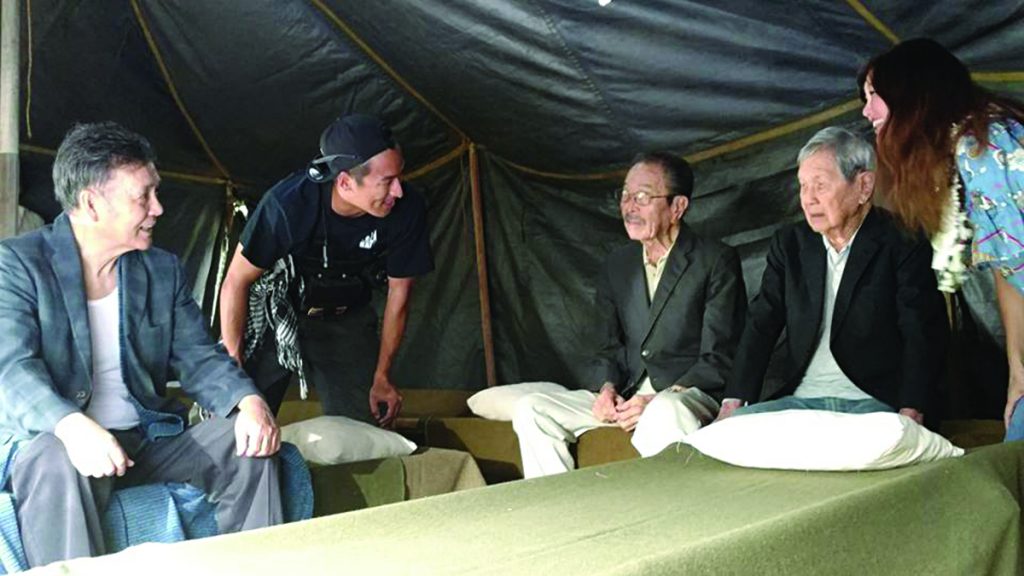

It’s taken local girl Stacey Hayashi more than 15 years to bring this story of the 100th/442nd and MIS to the big screen. Her dream — to perpetuate stories like this for today’s youth and for future generations — took perseverance and sacrifice, like that of the veterans she passionately honors with this film.

To make her dream come true, the software engineer had to become a filmmaker. She had to become a fundraiser. She had to gather resources, conduct interviews, and write the screenplay. There was a lot to learn. But the resourceful serial entrepreneur, writer, and designer was determined that somehow, the stories of veterans who became her dear friends and family would be told.

“People know about the 100th/442 and the bravery they showed, fighting the enemy in Europe, liberating towns in Italy and France,” she said. “But most people don’t know what had to happen for the 100th or 442nd to even be formed,” she added, referring to the racial discrimination faced by Japanese in Hawai‘i and the U.S. West Coast before and after December 7.

Stacey believes that “films can be powerful tools in bringing stories to light and keeping them alive, as well as a source of healing.”

“Sharing stories or seeing them told can be cathartic for survivors. Hopefully, it will also open up dialogue between survivors and their families,” she said. “Though we couldn’t tell every story, I tried to include as many as we could. I hoped to capture the spirit of who they were and are, their happy-go-lucky attitudes and kolohe natures, even in the face of such great adversity.”

She wished all her veteran friends would see the film and know that they were remembered and appreciated. Sadly, Assoc. Producer Eddie Yamasaki of the 442nd RCT I Company, who helped champion the movie for 15 years, died a few months before its release. Also, Congressman K. Mark Takai, a steadfast advocate, succumbed to cancer in 2016. The film is dedicated to his memory.

Journey of Heroes

Stacey didn’t just become a filmmaker in her quest to share what she calls “the inspiring true story you’ve never heard, about heroes you didn’t know existed.” She also became a rising star in the world of comic books and Japanese anime and manga, writing and self-publishing a comic book, “Journey of Heroes: The Story of the 100th Infantry Battalion and 442nd Regimental Combat Team.” The historically accurate graphic novel, illustrated by Damon Wong, features cute characters that look a lot like the veterans they represent.

Thousands of the comic books have been donated to schools across Hawai‘i and the United States, introducing real-life heroes and perpetuating their stories for today’s youth and generations to come.

The great legacy of the greatest generation

Almost all of our WWII veterans are gone now, including Stacey’s great-uncles who served in the original 100th Battalion and the 442.

And through this film, Stacey is doing her part to keep alive the great legacy of the nisei veterans — a small part of the greatest generation.

“Fear and racism are not good for anyone or any country, especially America, a nation of immigrants.” — Stacey Hayashi

Timeline: 1940 – 1946

100th Battalion/442nd RCT

Oct. 15, 1940 :: 298th and 299th Infantry Regiments of the Hawai‘i National Guard (HNG) are activated and integrated into the U.S. Army.

[In the 12 months preceding the attack on Pearl Harbor, approximately half of the 3,000 men in Hawai‘i who are either drafted or volunteer for service in the U.S. Army are Americans of Japanese Ancestry (AJA). Most are assigned to the 298th or 299th with some assigned to engineer units. Basic training is at Schofield Barracks on O‘ahu.]

Dec. 7, 1941 :: Japan launches a surprise attack on the Pearl Harbor naval base, home of the U.S. Pacific Fleet. Members of the 2nd Battalion of the 298th guard the windward coastline of O‘ahu, while the 1st Battalion is stationed at Schofield Barracks. Martial law is declared.

Dec. 8, 1941 :: United States declares war on Japan. FBI agents and police begin arresting Japanese community leaders in Hawai‘i, eventually detaining about 1,400 individuals who are classified as “dangerous enemy aliens.”

Dec. 11, 1941 :: U.S. declares war on Germany and Italy.

Jan. 5, 1942 :: War Department classifies AJA men of draft

age 4-C, “enemy aliens,” ineligible for military service.

Jan. 19, 1942 :: 317 AJA reservists with the Hawai’i Territorial Guard (HTG) — many had been members of the University ROTC — are classified 4-C and discharged without explanation.

Feb. 9, 1942 :: War Department orders General Delos C.

Emmons, Commanding General of the Army Air Force in Hawai‘i, to suspend employment of all ethnic Japanese

civilians in the Army.

Feb. 19, 1942 :: President Franklin D. Roosevelt signs Executive Order 9066, leading to the incarceration of more than 110,000 residents of Japanese ancestry in internment camps throughout the United States.

Feb. 23, 1942 :: Having been discharged from the HTG, AJA men band together to form the Varsity Victory Volunteers (VVV), a labor unit under the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

May 26, 1942 :: General George C. Marshall, Army Chief of Staff, establishes the Hawaiian Provisional Infantry Battalion, to be made up of AJAs from the Hawai‘i National Guard’s 298th and 299th Infantry and other units.

May 28, 1942 :: 1,432 men gather at Schofield Barracks to join the new Hawaiian Provisional Infantry Battalion. The unit is led by Lieutenant Colonel Farrant Turner; second in command is executive officer James Lovell.

Jun. 5, 1942 :: Hawaiian Provisional Infantry Battalion boards the transport ship, S.S. Maui, and departs Honolulu.

Jun. 12, 1942 :: Battalion arrives in Oakland and is officially activated as the 100th Infantry Battalion (Separate). The “Separate” status indicates the battalion is not assigned to a parent unit. Soldiers start calling their battalion One Puka Puka (Hawaiian word meaning hole).

Jun. 16, 1942 :: 100th arrives at Camp McCoy, Wisconsin, where they undergo training until the end of Dec. The battalion quickly earns a reputation for superior performance in the field.

Jun. 26, 1942 :: Army Chief of Staff recommends the formation of a Board of Military Utilization of U.S. Citizens of Japanese Ancestry to determine whether a Japanese American unit should be sent to fight in Europe.

Oct. 2, 1942 :: Elmer Davis, Director of the Office of War Information, recommends to President Roosevelt that Japanese Americans be allowed to enlist for military service.

Nov. 3, 1942 :: Twenty-five men from the 100th (Company B, Third Platoon) plus three officers and a cook depart Camp McCoy for Ship and Cat Islands off the Mississippi Gulf Coast where they will be used to train dogs to recognize and attack Japanese soldiers based on their supposedly unique scent.

Nov.– Dec. 1942 :: Sixty-seven men from the 100th are recruited for the Military Intelligence Service (MIS) because they had gone to school in Japan or were familiar with the Japanese language. They are sent to Camp Savage, Minnesota, for training.

Jan. 6, 1943 :: 100th leaves Camp McCoy for further training at Camp Shelby, Mississippi; then four months later, to Camp Claiborne in Louisiana for field maneuvers until June.

Jan. 28, 1943 :: Impressed by the outstanding performance of the 100th, the War Dept. announces plans to organize an all-Japanese American combat unit. The call goes out for 1,500 volunteers from Hawai‘i; nearly 10,000 respond. A quota of 3,000 is established on the mainland, but the response is 1,200 — mostly from internment camps.

Jan. 31, 1943 :: Varsity Victory Volunteers in Hawai‘i request the deactivation of their unit so its members can enlist in the new 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

Feb. 1, 1943 :: 442nd Regimental Combat Team is activated by President Roosevelt.

Mar. 28, 1943 :: Honolulu Chamber of Commerce sponsors

a farewell ceremony at ‘Iolani Palace for the initial 2,686 AJA volunteers of the 442nd RCT.

May 1943 :: 442nd RCT begins training at Camp Shelby, Mississippi, where they’ll meet up with the 100th for the first time in June after the 100th returns from maneuvers in Louisiana.

Jul. 20, 1943 :: 100th receives its battalion colors and motto, “Remember Pearl Harbor,” as requested by the unit. The battalion leaves Camp Shelby on Aug. 11 for Camp Kilmer, New Jersey; then to Staten Island and they board the SS James Parker, departing on August 21.

Sept. 2, 1943 :: Battalion lands at Oran, Algeria in North

Africa. Fifth Army command wants the 100th to guard supply trains, but Colonel Turner insists they be committed to combat duty. The 100th is assigned to 34th “Red Bull” Division, which has more battle experience than any other American Army unit at that time.

Sept. 19 – 22, 1943 :: 100th ships out with the 133rd Infantry Regiment, 34th Infantry Division. They land on the beaches at Salerno, Italy on September 22.

Sept. 29, 1943 :: On the first day of combat, Shigeo “Joe” Takata is the first member of the 100th to be killed in action and the first to receive the Distinguished Service Cross.

Oct.– Nov. 1943 :: 133rd Infantry Regiment, including 100th, fights a series of battles in several Italian towns and launches attacks on German forces, crossing the Volturno River three times. Major James L. Gillespie replaces Lt. Col. Turner.

Mid Jan. 1944 :: Battle of Monte Cassino begins. It takes four major assaults and four months to defeat German forces. By some estimates, the battle leaves 250,000 people dead or wounded. The 100th fights in the first two assaults before it is relieved on Feb. 15. Having suffered heavy casualties during its months in combat, the unit becomes known as “The Purple Heart Battalion.” After Cassino, the first group of officers and enlisted men from the 442nd arrives to replenish the depleted battalion.

Jan. 29, 1944 :: Major James Lovell assumes command of the battalion after being released from the hospital, replacing Major Caspar Clough. He is soon badly wounded and does not return to combat. By the end of war, the 100th has 13 changes of battalion commanders.

Mar. 26, 1944 :: 100th lands at Anzio, the second front between the German’s Gustav Line of defense and Rome and is assigned a section in the Anzio beachhead in April.

May 1, 1944 :: 442nd RCT leaves Virginia for Europe.

May 11, 1944 :: British, French and U.S. forces push to Rome.

Jun. 2, 1944 :: 100th participates in the breakout to Rome by attacking and capturing Lanuvio. Rome falls three days later.

Jun. 11, 1944 :: 100th meets up with 442nd Regimental Combat Team in Civitavecchia, northwest of Rome. At this time, the Regiment consists of the 3rd Battalion, 522nd Field Artillery Battalion and 232nd Engineer Company. The 2nd Battalion will arrive six days later. The 1st Battalion, which has been depleted from sending replacements to the 100th, is left at Camp Shelby to train new arrivals.

Jun. 22, 1944 :: President Roosevelt signs into law the Service members’ Readjustment Act of 1944, commonly known as the G.I. Bill of Rights. By the time the original G.I. Bill ends in July 1956, 7.8 million World War II veterans will have participated in an education or training program and 2.4 million veterans will have home loans backed by the Veterans Administration.

Jun. 26, 1944 :: 442nd RCT is assigned to the Fifth Army and, in turn, is attached to the 34th “Red Bull” Division. The battle-tested 100th Infantry Battalion is attached to the 442nd RCT, becoming the 1st Battalion of 442nd, but retains its name, 100th Infantry Battalion, because of its outstanding combat record. By this time,

the battalion of 1,300 has suffered more than 900 casualties. The 100th/442nd RCT goes into combat near Belvedere, Italy.

Jul. 7, 1944 :: 100th/442nd RCT takes Hill 140 in Italy after a bitter battle.

Jul. 9, 1944 :: 100th occupies Leghorn (Livorno) and is directly under the command of Fifth Army in Rome.

Jul. 27, 1944 :: General Mark Clark presents the Presidential Unit Citation, the highest honor in the Army for a military unit, to the 100th at Vada, Italy, for action at Belvedere. By this time, soldiers of the battalion have been awarded 9 Distinguished Service Crosses, 44 Silver Stars, 31 Bronze Stars, 3 Legion of Merits, 15 battlefield commissions, and more than 1,000 Purple Hearts.

Aug. 14, 1944 :: 100th is formally attached to the 442nd RCT.

Aug. 31, 1944 :: 442nd, minus the 100th, reaches the Arno River near Florence, Italy. The 100th spearheads the crossing of the Arno River and captures Pisa.

Sept. 1944 :: While the 100th waits in Naples for the movement into France, representatives from each company meet to approve a set of bylaws for Club 100. They elect Katsumi “Doc” Kometani

as president, Sakae Takahashi as vice president, Andrew Okamura

as secretary, and Hideo Yamashita as treasurer. Leslie Deacon, Joseph Farrington, and Charles Hemenway are named honorary members.

Sept. 27, 1944 :: 100th/442nd RCT leaves Naples for France.

Sept. 30, 1944 :: 100th/442nd RCT is attached to the 36th Division, also known as the Texas Division, of the Seventh Army.

Oct. 15, 1944 :: 100th/442nd RCT enters the battle of Bruyeres in the Vosges Mountains, located in northeast France. After three days of fighting, the 100th takes Hill A and the 2nd Battalion takes Hill B and enters the town. Two days later, the 100th captures Hill C.

Oct. 25, 1944 :: 100th/442nd RCT captures Biffontaine.

Oct. 26 – 31, 1944 :: After five days of fighting, the100th/442nd RCT rescues 211 members of the Texas “Lost Battalion,” 141st Regiment, 36th Infantry Division, which was cut off and surrounded by Germans. The 100th/442nd suffers more than 800 casualties, including 184 killed in action. 100th earns its second Presidential Unit Citation for actions at Biffontaine and Lost Battalion rescue. Presidential Unit Citations are also awarded to the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, the 232nd Engineer Combat Company, and F and L Companies of the 442nd.

Nov. 13, 1944 – Mar. 1945 :: Soldiers of the 100th/442nd RCT head south to the French Riviera, where so many were lost that it can’t be used as a regiment-sized force. Nearly 2,000 are wounded and in hospitals in Italy, France, England and the United States. The unit guards a 12-mile stretch of the French-Italian border. The men call this time “the Champagne Campaign.”

Mar. 20, 1945 :: The 100th /442nd RCT, minus the 522nd Field Artillery Battalion, leaves to join the African-American 92nd Infantry Division.

Apr. 5 – 6, 1945 :: 100th/442nd RCT makes a surprise attack on Nazi mountainside positions in Italy, breaking through the German Gothic Line in one day. The regiment receives the Presidential Unit Citation.

Apr. 6 – 30, 1945 :: 100th/442nd RCT drives the enemy up the Italian coast to Genoa and Turin.

May 2, 1945 :: German army surrenders. The war in Italy is over. Six days later, on May 8, with Germany’s unconditional surrender, the war in Europe is officially over.

Aug. 6, 1945 :: U.S. drops atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan. Three days later, an atomic bomb is dropped on Nagasaki.

Aug. 15, 1945 :: Victory in Japan Day, signaling end of WWII.

Sept. 2, 1945 :: Japan signs the formal Instrument of Surrender.

Jul. 4, 1946 :: Members of the 100th /442nd RCT sail into New York Harbor aboard the SS Wilson Victory and are greeted by cheering crowds.

Jul. 15, 1946 :: A parade and review is held in Washington, D.C. President Harry Truman pins the Presidential Unit Citation on the 100th/442nd RCT colors. “You fought not only the enemy,” he says, “but you fought prejudice — and you have won.”

Aug. 15, 1946 :: The colors of the 100th Infantry Battalion are officially turned over to the Territory of Hawai‘i during a ceremony in Honolulu for returning war veterans. With that act, the battalion is deactivated.

Content used by permission of the 100th Infantry Battalion Veterans Education Center

808-946-0272 | www.100thbattalion.org

Leave a Reply