Cover & Feature Story Photography by Brian Suda

“We believe that the future of HUOA is dependent upon our youth.” — Jane Serikaku

Norman Nakasone, HUOA President

When we first meet someone new in Hawai‘i, we often ask, “Where you wen’ grad?”, as it gives us an idea of where they grew up and a lot of times we know someone in common.

Likewise, Okinawans ask, “Are you Uchinanchu”? If yes, then the next question is, “What club do you belong to?”

Today, there are 49 active Okinawan clubs that make up The Hawai‘i United Okinawa Association (HUOA), a non-profit organization whose mission is to promote, perpetuate and preserve Okinawan culture. Its combined membership exceeds 40,000 people. The club to which someone belongs is often based on from which Okinawan city, town or village his/her family originated. Okinawan immigrants who settled in Hawai‘i recreated their village communities using names like shi (city), cho (town), son (village) and aza (ward/neighborhood). Today the clubs are known more by Shijinkai, Chojinkai, Sonjinkai and Azajinkai. The term jinkai literally means “peoples club or organization.”

Okinawans started immigrating to Hawai‘i in 1899. The then governor, Shigeru Narahara, allowed civil rights leader Kyuzo Toyama to recruit 26 men to work on Hawai‘i’s ‘Ewa plantations.

From 1900 –1907, open immigration brought thousands of workers who were hoping for a better life to the plantations. Plantation work was hard and demeaning — 10-hour days, 6 days a week under the brutal sun. Okinawans also endured double discrimination from both the local population and their fellow Japanese workers who treated them as second-class citizens. At the peak, some 1,700 Okinawan immigrants had settled in Hawai‘i.

Chimu’ubii, or remembrance, is an important value within the Okinawan community. With each passing decade, the paths on which Okinawans in Hawai‘i traveled become increasingly distant. The homeland and villages are far away. And many customs and traditions have faded. Yet, these are the cultural traits that helped the Okinawan’s adopt Hawai‘i as home, assimi-late to American society and provide for their families. Hawai‘i’s vibrant Okinawan clubs play an important role in preserving Okinawan culture and its unique attributes.

In 1951, the clubs united to form the Hawai‘i Okinawa-Jin Rengo-Kai (United Okinawan Association of Hawai‘i) in order to provide relief for Okinawa after WWII. Through this local community effort, HUOA (name changed in 1995) became a major partner in the local Okinawan community. It focused on improvements in agriculture, public health, medical services, education and leadership training.

Nearly 30 years later, the HUOA built the Hawai‘i Okinawa Center in honor of its hard-working Issei (first generation forefathers), who persevered for the sake of future generations. The Center perpetuates the “Uchinanchu spirit.” It hosts regular performing art events and various cultural classes. But perhaps most importantly, it provides children and young adults opportunities to learn about their culture and to be part of the Okinawan community.

“We believe that the future of HUOA is dependent upon our youth,” says Jane Serikaku, HUOA Executive Director. As a retired educator of 30 years, she wanted to give young adults the chance to become totally immersed in the Okinawan culture, history and its people. As such, she created a Young Leadership Study Tour to Okinawa, which was patterned after the 1980 Leadership Tour offered by the Okinawan Government. Many participants returned excited and became leaders of their own club and/or became leaders of HUOA.

Jane has also been the HUOA coordinator for the Okinawa-Hawai‘i High School Student Exchange program for the past 21 years. “In the Exchange Program, 25 Okinawan students arrive in Hawai‘i in March and experience a two-week home stay with families and attend school with our students,” Jane explains. “In exchange, our Hawai‘i students engage in a two-week home stay experience in Okinawa in June.”

As a nonprofit, the Hawai‘i Okinawa Center has a very small staff. Its activities, events and services are mostly supported by volunteers.“We are extremely appreciative of the many volunteers who spend their days at our Center working to keep our Takakura Garden and Issei Garden well manicured and beautiful,” Jane says.

She notes that additional volunteers maintain the library of treasured books, offer translation services, help with family history research, assist in the office or fundraise at craft fairs. “We hope that this love for the Hawai‘i Okinawa Center will continue in the years to come,” Jane says, “and that more people will volunteer to take good care of their ‘home away from home.’”

In the near future, the HUOA is looking to expand. “We have our eyes set on the land just across the street,” Jane says. “We’d like to build a Hawai‘i Okinawa Plaza as a means of financially supporting the Hawai‘i Okinawa Center for future generations.”

Special thanks HUOA member club Hui O Laulima for use of its book, Chimugukuru, as reference source for this article.

The Local Okinawa Families That Built Hawai‘i

From Kaua‘i to the Court House

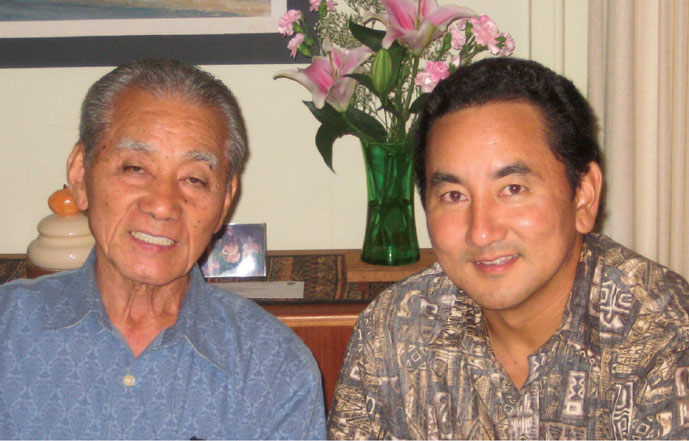

Choyu Shimabukuro grew up in Haneji, Okinawa, an area outside of Nago. He later immigrated to Wahiawa¯, Kaua‘i. Choyu, which means long courage, passed on the Okinawan values of hard work to his son Herbert. As such, Herbert moved to O‘ahu and attended Farrington High School and The University of Hawai‘i. He later attended law school at George Washington University in Washington D.C. His career in law and as a judge spanned some 40-plus years.

Herbert’s belonged to the Haneji Club for more than 50 years. He served as President for one year in 1987 and then for a second term from 2001-2010. Over the years, the club has offered Herbert and his family wonderful fellowship.

His son, Chris, has fond memories of attending many of the club’s activities, including the Annual Picnic, volunteering at the Okinawan festival, and playing on softball and volleyball leagues. Chris says that he appreciates how the club has given him a sense of identity.

Chris is now a Vice President of the HUOA and has chaired the organization’s homeless Community Outreach Picnic and co-chaired the Aloha Aina Earth Day recycling event. He is also the Development Director at ‘Iolani School, one of the finest private institutions in the nation.

From Hilo to Kalihi

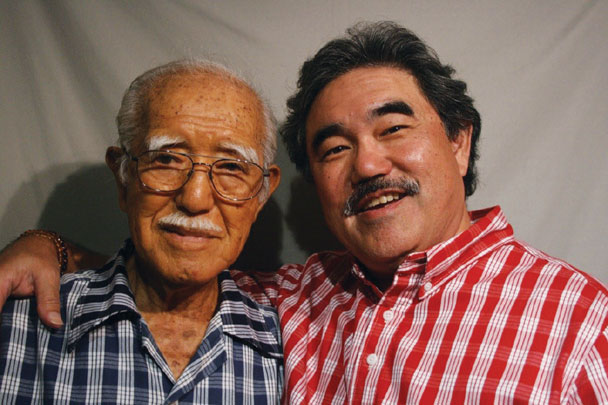

In 1941, immigrants Chogen and Yoshiko Tamashiro opened the first Tamashiro Market in Hilo, Hawai‘i. It was a small store specializing in fresh pork from livestock farmed by the Tamashiro family. On April 1, 1946, a tsunami struck and demolished most of Hilo’s business district, including the family’s store. Chogen move the business to O‘ahu to its current location on North King Street.

The Tamashiro’s older son, Walter Hajime, took over the operation in 1954. He built the business by specializing in seafood. He started with a few pieces of ‘opelu, then a whole aku (skipjack tuna). The few pieces of fish grew to tubs of fish, larger fish and dozens of varieties. Brother Johnny Tamashiro and brother-in-law Larry Konishi joined Walter in 1962, and together they expanded the Market’s reputation as the home of the finest seafood. In fact, Tamashiro Market was one of the first retailers to sell poke on a large scale and has offered more than 30 preparations since the 1970s. Today, Walter’s sons Cyrus, Guy and Sean continue the family business.

The Tamashiro family has been involved with their Okinawan Nago Club many years, as well as fundraising of the Okinawan Cultural Center. In 2012, Cyrus will become the President of the Hawai‘i United Okinawan Association.

Arakawa Store

In 1904, Goro Arakawa was one of the earliest plantation workers’ to work on Hawai‘i’s Ewa plain. During The Great Strike of 1909, he empathized with the workers demands for higher wages and better standard of living. To help the community, he partnered with Mr. Tamanaha to open the Arakawa Store in 1912.

Goro was one of 9 children—5 boys and 4 girls—who worked at the family store. Goro was chosen to attend New York University to study retailing and marketing. Seeing that his siblings worked long, hard hours at the store, he was pressed to study hard for the family. When Goro returned to Hawai‘i, he made the Arakawa Store one of the first retailers to accept credit cards in the state of Hawai‘i.

In the late 1980s, Goro became involved with the Hawai‘i United Okinawan Association when the Arakawa family was approached about fundraising for the Okinawan Cultural Center.

Goro was also the spark plug for the founding of the Waipahu Plantation Village, an outdoor replica of a Hawai‘i sugar plantation village.

Goro’s son, David, carries on the family Okinawan tradition of giving back to the community. As a past HUOA President and former Prosecuting Attorney, David is now the President of the United Japanese Society of Hawai‘i, the umbrella of all the Japanese associations.

Leave a Reply