Our “can do!” island culture values resourcefulness and cooperation when faced with challenges. “We know a guy” and where to get things, and have honed skills tūtū taught us. We don’t expect anything in return for helping out. “If can, can; if no can, no can.” We put ourselves to the task.

Our “can do!” island culture values resourcefulness and cooperation when faced with challenges. “We know a guy” and where to get things, and have honed skills tūtū taught us. We don’t expect anything in return for helping out. “If can, can; if no can, no can.” We put ourselves to the task.

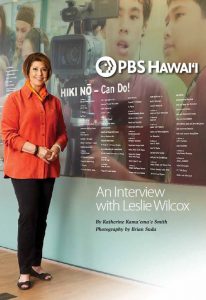

PBS Hawai‘i (KHET or KMEB call letters in your guide) is our TV station. Our donations built it and it serves us. But don’t take it for granted. Paula Kerger, president of the Corporation of Public Broadcasting national nonprofit, recently applauded our “can do!” public television station: “This is truly, I would say, the most exceptional station in our country…

it understands what it means to be a part of the fabric of our community.”

“NOVA,” “Get Caught Reading,” “HIKI NŌ,” “PBS News Hour,” “Long Story Short with Leslie Wilcox”— we are fans! But how much do we know about our TV station?

Snuggle up. We turned the tables and interviewed PBS Hawai‘i President and CEO Leslie Wilcox. Be prepared for some learning moments! And into the bargain, Leslie shares memories about growing up on O‘ahu — another reason PBS Hawai‘i expresses the heart and soul of our islands.

Generations Magazine readers watch PBS, but they may not understand how it got started.

LW: Well, Hawai‘i public television goes back to 1965, when a University of Hawai‘i professor set up closed-circuit instruction on campus. With the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967, the UH initiative became a member of the new Public Broadcasting Service [PBS]. In 1969, they introduced “Sesame Street.” It was controversial in some states, but Hawai‘i welcomed the educational program.

We were first located in a vacant lower Mānoa corner of UH near some Quonset huts. Back then, the TV station was part of the state government. Later, in 1972, the State Legislature funded a two-story building on the site. From the start, our public television station racked up a number of Hawai‘i firsts — including the first local station to provide live satellite broadcasts.

Can everyone can get PBS on an HDTV?

LW: Yes, plus via cable, satellite or online. We serve most of the Hawai‘i community free via our KHET and KMEB over-the-air broadcast signals — including financially disadvantaged communities where it’s not profitable for commercial TV stations to direct their signal. For example, we recently strengthened free service to the under-resourced, rural southern end of the Big Island. Many people do not have digital access and we care about them. That’s why we broadcast educational programming 24 hours a day on two channels — our main channel and PBS KIDS 24/7.

When state funding ended in 2000 and we became a private, nonprofit, community-supported organization, we began leasing the space we had long occupied at UH Mānoa. I joined in 2007. Years later, due to UH space needs, we lost our lease and had to move all of our operations.

When did PBS Hawai‘i make the big move?

LW: We moved in 2016, but before that, we raised $30 million to build a big new facility across town. Relocation at first seemed like bad news and a tough blow, but like many changes, it worked out for the better. We had hopes, dreams, hard work and a “can do!” attitude. As always, “the village” of Hawai‘i nei offered support. And we had a strong staff committee headed by Karen Yamamoto managing the move.

In May 2016, we settled into our beautiful, future-facing multimedia building at the corner of Nimitz Highway and Sand Island Access Road in Kalihi Kai — the PBS Hawai‘i Clarence T.C. Ching Campus. It’s the best work environment I’ve ever had — open, cheerful, welcoming, functional to the max. Thanks to our terrific unpaid board of directors and funding by Hawai‘i individuals, businesses and charitable foundations, the facility and land are debt-free .

We’re delighted to be owners, not renters of the only locally-owned, statewide broadcasting company. All others are commercial businesses owned by large companies based elsewhere.

PBS consistently provides content and services to inform, educate and enlighten our fellow islanders. We gather feedback from stakeholders, viewers and our statewide independent community advisory board.

We want to inspire lifelong learning from childhood through active retirement and elder years. The PBS Hawai‘i mission, with its pillars of education and journalism, is a great fit with my personal philosophy. Education certainly lifted my prospects in life. And journalism increases a flow of new information. For more than three decades in journalism, I felt like I was being paid to learn.

At PBS Hawai‘i, our traditional values of integrity and fairness endure, but our methods and approaches have changed repeatedly over time with waves of new technology and with shifts in societal perspectives. Sometimes, even media professionals have difficulty dealing with change. As former Sony CEO Howard Stringer said, “We all have to remember not to hang on to the status quo long after the status has lost its quo.”

Also, PBS values adaptability and versatility. Our lean, dedicated staff has the energy, creativity and know-how to produce a significant amount of local content — weekly TV programs and frequent online offerings. We are “can do!” people.

Is it true that you are not funded by the state?

LW: Yes. We’re Hawai‘i’s sole member of the trusted private nonprofit Public Broadcasting Service. A related national entity is the private nonprofit Corporation for Public Broadcasting. It distributes federal funding to some 350 public TV and radio stations. These funds only make up 15 percent of our annual budget. We leverage PBS federal grant monies into many more private dollars, thanks to generous individual, business and foundation donors. For a number of reasons, it’s good to have different kinds of revenue streams. For example, if a funder seeks to control our editorial content, we need to stand strong — and we can, with other sources of funding.

We remember you reporting news on the air at KGMB-TV and KHON2. Did journalism bring you to Hawai‘i?

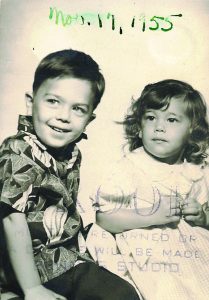

LW: Actually, I was born and raised on O‘ahu. My Portuguese forebears, Joao and Faustina Fraga Silveira, sailed here while Hawai‘i was still a monarchy. They had actually met on the ship, settled in Kalihi and had 16 children, 13 of whom survived childhood. One of the grandchildren was my mother, Blanche. During World War II, she met Paul Wilcox, a soldier stationed here. He fell in love with my mother and Hawai‘i. Dad had a great broadcast voice and became one of Hawai‘i’s early radio disc jockeys with a late-night show called the “Midnight Owl.” He later worked in radio sales. I’m in the middle of five siblings. I attended Holy Nativity School, Āina Haina Elementary, Niu Valley Intermediate and Kalani High before going to college.

Small-kid times were spent in what were once jokingly called “the boonies,” meaning Kuli‘ou‘ou Valley, with Quonset huts here and there, a farm market, and backyards where families grew veggies and flowers. Kuli‘ou‘ou was the last residential valley in East Honolulu. As a kid, I remember pink bulldozers tracking down Kalanianaole Highway to build Henry Kaiser’s huge new Hawaii Kai marina community around the ancient Hawaiian fishpond, Kuapā. Pink was Mrs. Kaiser’s favorite color. I can still remember the sparsely settled lands, dotted here and there with small farms.

Small-kid times were spent in what were once jokingly called “the boonies,” meaning Kuli‘ou‘ou Valley, with Quonset huts here and there, a farm market, and backyards where families grew veggies and flowers. Kuli‘ou‘ou was the last residential valley in East Honolulu. As a kid, I remember pink bulldozers tracking down Kalanianaole Highway to build Henry Kaiser’s huge new Hawaii Kai marina community around the ancient Hawaiian fishpond, Kuapā. Pink was Mrs. Kaiser’s favorite color. I can still remember the sparsely settled lands, dotted here and there with small farms.

My older brother Pat and I would walk across the highway, wade out to a little islet and pretend to be island castaways.

When fishermen abandoned fresh aku heads there, we’d stage aku-head swordfights. And we played with sea cucumbers, which squirted seawater. Dumb kids. I wouldn’t do this today.

In high surf, waves rolled across the road into the fishpond. The backwash left mullet stranded on the land. We kids were there to pick them up and proudly take a “fresh catch” home for dinner!

Freedom and make-believe are treasures of a post-war Hawai‘i childhood.

LW: The world was certainly a safer place; baby boom children kept themselves occupied and were allowed to roam. On Saturdays, our mothers might say, “Just make sure you come home before dark. And don’t bother anyone or get into trouble.” No cellphones or bottles of water required.

When I was still in grade school, my family moved into the new Niu Valley subdivision, then considered a middle-class community. I was older and now our keiki explorations involved crawling around in mountain lava tubes, reef diving to look for eel holes and lots of skateboarding down steep streets. I have the scars to prove it.

I learned to surf with my friend David’s old homemade board and reveled in the freedom. We also surfed Kawaikui Beach. When we got thirsty, we dove down and drank fresh water flowing through pockets in the sand. Highway work

stopped the flow of artesian water. Niu pier is long gone, too. Great memories.

What was your first job after high school?

LW: Waitressing at the old Snack Shop on the grounds of the Royal Hawaiian Hotel. My pink uniform had a big bow in the back ironed with starch from Chinatown; it was hard as a board.

I won a journalism scholarship to USC, but just before high school graduation, my parents divorced and bankruptcy followed. I stayed home to help support the family. Fortunately, I was able to pay for and attend UH Mānoa after the Honolulu Star-Bulletin, then the largest newspaper in Hawai‘i, gave me an errand-person job. Amazingly, it turned into a full-time reporting position when I was barely 19. I’m forever grateful to my former Star-Bull colleagues, who at times teased but also generously helped an awkward rookie.

Were there other mentors along the way?

LW: I’ve had too many guides and mentors to mention, and they remain in my heart. Some offered guidance, others taught by example in a critical moment. I learned from “the village” that I came to know as a journalist — at many locations across the state and under stressful, sorrowful or even dangerous circumstances.

Also I learned from reading. Books open up history, context, new ideas, other worlds, flights of fancy and knowledge of how things work. I didn’t travel outside Hawai‘i until I was 16 (for a journalism competition), but through reading, I had already crossed continents, gone back in time and seen the future. Reading continues to inform my writing and expand my understanding.

Also, my extended family members are observant and curious. “I wonder why…” was a common beginning to a sentence. It wasn’t a gossipy or nosy interest. The question connects things to history, science or community. This curiosity cultivated my sense of wonder, too. When I was 15, I researched the purchase of a big parcel of land in our neighborhood — I wondered who bought it and how it might affect life in the area. Come to think of it, that was pretty niele [nosy]!

Sounds like you were cut out to be a reporter. How was the transition to television?

Sounds like you were cut out to be a reporter. How was the transition to television?

LW: The first thing I learned in TV is that perception is reality. My newspaper background taught me how to gather and write news. But I was pitiful presenting news on camera. If you report with a quivering voice, your viewers are going to think something is shaky about your report, too!

KGMB-TV news director and icon Bob Sevey had recruited me, knowing I had no television experience. I told him that my own mother thought I looked and sounded goofy and unsure, and asked him for his professional advice. His candid,

old-school response: “Wilcox, you’ll get there. You’d better — this is a sink-or-swim business.”

I didn’t grow up watching women role models on television news. Men dominated the business. Fortunately, three talented women were successfully navigating the newsroom — Linda Coble, Bambi Weil (who later became Judge Eden Hifo) and Carolyn Tanaka. Finally, I got it together by deciding simply to be myself. I pictured my dear no-nonsense auntie and my favorite math teacher, Mr. Charles Hirashiki, watching at home — and I delivered the news to them. It worked.

After mastering broadcasting, what spurred you to take the helm of PBS in 2007?

LW: The magnetic pull of PBS Hawai‘i was and is still this: it is locally owned and locally managed to serve fellow islanders. We enrich others by telling authentic Pacific stories and opening windows to the world. I wanted to be a part of this mission.

One misconception about public media is that the “public” stands for government. It actually stands for you and me, and our whole community. After 13 years, still I am amazed and inspired by people who send us money to keep doing what we’re doing.

I like working for a local organization with strong national and international alliances through public broadcasting. Yet, our volunteer board members and professional staff live in the islands. We are approachable and accountable.

I like working for a local organization with strong national and international alliances through public broadcasting. Yet, our volunteer board members and professional staff live in the islands. We are approachable and accountable.

Some of our sponsors choose to share with others something they deeply value. Your readers may not know that Maui grandparents Jim and Susan Bendon of Sprecklesville sponsor the lessons of Daniel Tiger [“Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood”] for all of Hawai‘i’s children. Retired UH professor Belinda Aquino still provides education for all of us by underwriting broadcasts of “Nature” and “NOVA.” Rick Nakashima of Ruby Tuesday restaurants supports the “Get Caught Reading” literacy initiative. I can’t imagine a better job.

What were the most important changes you brought to PBS when you started?

LW: I came with a deep respect for what this station had already achieved, but media technology and capabilities were changing rapidly, so I encouraged a corporate culture that welcomed new skill sets. Then you need to react and respond quickly in these fast-changing times, so I adopted a “flat” organizational structure that allows information from different sources to move quickly through the organization.

That brings us to “Long Story Short with Leslie Wilcox.” How do you get your guests to reveal so much new information?

LW: When people know that you earnestly want to know them and their views, it’s usually easier for them to relax and express themselves. In my gut is always the “I wonder why or how” question, but active listening is what I mainly do I’m not thinking of my next question while the guest is answering the current question.

How about the wonderful forums and discussions? That’s more than listening.

LW: We’re here to ask the questions that people at home want answered. PBS Hawai‘i takes a “can do!” approach to convening diverse voices and maintaining a respectful discussion. We offer a safe, trusted space where community members with opposing opinions may be heard. “Insights on PBS Hawai‘i,” “KĀKOU: Hawai‘i’s Town Hall” and “What’s It Going to Take?” are discussion forums. Our moderators, Daryl Huff, Yunji DeNies and Lara Yamada, are comfortable being around people with conflicting opinions, and they know that if conversations can be kept civil and even respectful, there’s a better chance of people really hearing each other and finding common ground.

Shouting over others, name-calling and public shaming run counter to island values. At PBS Hawai‘i, we want to keep things real and at the same time respectful, non-partisan and fair.

* * *

Leslie, we thank you, your dedicated board of directors and the entire PBS Hawai‘i family for sharing this inside look — and we are so very grateful for all they do. I learned a lot more about PBS Hawai‘i — and all the work that goes into creating and delivering us wonderful, high-quality programs. Going forward, I encourage our readers to join me and support PBS Hawai‘i however we can. After all, it’s our TV station! “Can do!”

To learn more about PBS Hawai‘i, visit www.PBSHawaii.org and www.wikipedia.org. We don’t have to wait to donate — online we can give a one-time gift or subscribe to make monthly donations all year long.

Photography by Brian Suda

Leave a Reply