Caregivers Kalani Pe‘a & mom, Pua

Caring for a loved one with Alzheimer’s disease requires patience, compassion, understanding and endless, unconditional love. In the following pages, Kalani Pe‘a and his mother, Pua, share the story of Lu Kahunani; Pua’s mother, Kalani’s grandmother. “I saw her slipping away. I knew I was going to lose her one day…”

She was a dynamo; a no-nonsense force of nature; a feisty fireball. She was a wise woman with a huge heart. But she did not mince words. She passed her pragmatic knowledge and deep-rooted values to her seven children. “Be good to people,” she would tell them. “And stop crying so much,” Lu Kahunani would tell her grandson, Kalani Pe‘a.

She was a dynamo; a no-nonsense force of nature; a feisty fireball. She was a wise woman with a huge heart. But she did not mince words. She passed her pragmatic knowledge and deep-rooted values to her seven children. “Be good to people,” she would tell them. “And stop crying so much,” Lu Kahunani would tell her grandson, Kalani Pe‘a.

Music lovers in Hawai‘i and beyond know Kalani as a gifted, Nā Hōkū Hanohano and Grammy Award-winning singer and composer. It’s in his blood. He comes from a long line of musicians — his kūpuna. But he said he began to cry often when he saw his grandmother, who he calls “Mama.” “I love her so much and she is slipping away,” he said. He knew one day she’d be gone.

About 10 years ago, when her husband was still alive, Lu Kahunani began to lose her words. She started to misplace things. Sometimes she didn’t know where she was. Her husband noticed and asked their youngest daughter, Pua, to keep an eye on her.

Daughter Pua provided respite for her mother, caring for her father as he endured cancer and treatments. Before dying in his daughter’s arms later that year, he asked her to take care of his beloved wife. Pua then turned all of her attention to her mother, who was exhibiting signs of advancing Alzheimer’s disease.

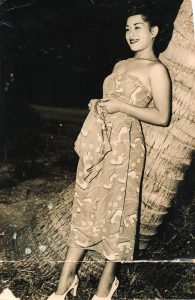

Lu Kahunani will turn 90 in November. She was a model in her younger days, with the beauty of a queen. Later, she raised a family and worked at hotels, restaurants and at KTA Super Stores in Hilo. “My Mama never complained,” says Kalani. “She was the matriarch of the family. She was very steadfast and strong-willed; always vigilant and industrious. If ever we complained about a problem she would say, ‘Get over it. Figure it out.’” Kalani admits to being a crybaby when he visited Mama, even before Alzheimer’s started to steal her body, mind and memories.

She would ask, “Why are you such a crybaby?” Kalani replied, “‘Because I love you so much.’ But in my head, I knew time was flying. I knew time was precious. I knew I would not have her forever. I saw her small hands become more frail and thin. I cried not just because I was a crybaby; I cried because I knew I was going to lose her one day.”

However, Kalani seldom saw his stoic Mama shed a tear. The first time was when he was 18, when his mother and grandmother took him to get settled in college in Colorado. It was their first time leaving the islands. “She cried because she said she was going to miss me.” But through her tears, she said a prayer that her grandson would do well in his college endeavors.

The second time he saw Mama cry was after Kalani’s mom, Pua, became her caretaker. “She realized she was forgetting things,” says Kalani. “She became aware of the state that she was in and how her condition might affect her family.” Kalani shed more tears as he witnessed his Mama break down.

During the first stages of her dementia, Mama was asked to retire from her job at KTA. She did not want to retire, but she had to.

“It was in 2009 that she started wandering; forgetting her place; forgetting where she left things,” said Pua.

“She started to catch herself. She was aware of what was happening to her. She began to experience what is called sundowners… dementia, agitation, forgetting where she was,” says Pua. She was assessed for Alzheimer’s in 2010.

For those with dementia, sunset can be a time of increased confusion, frustration and agitation. Sundowning is a symptom of mid-stage to advanced Alzheimer’s.

Pua says, “She asked me to do three things: ‘When I forget to speak for myself, be my voice. When I forget to think for myself, will you think for me? Will you please be me?’ So I became her.” Pua learned to put herself in her mother’ place in order to understand her and her needs and mālama her. Social workers would frequently call on her for advice, because, they said, “You know your mother.”

Because of her mother’s Alzheimer’s assessment, Pua was able to educate herself about the disease in order to best understand what was happening to her mother and how she could help her most effectively.

“I had to understand this disease,” Pua said. “It’s not curable. It worsens as time goes by. And you see that. I saw all that. So you really have to understand this disease so you can help. This was my job now.”

Parent as Child, Child as Parent

Parent as Child, Child as Parent

“When you’re a child, your parents think for you, speak for you, guide you, teach you and protect you. So now, she was like my child,” says Pua. “She looked at me as her mother. There were times when she called me mama. They went through difficulties raising us. Now it is our turn to care for them.”

Pua is the youngest of seven. While trying to provide the best care and create the optimal treatment plan for her mother, family discord erupted at an already stressful time. Pua’s “perfect, no-brainer plan” to involve her six siblings in her mother’s care (seven siblings, each caretaking one day a week) did not come to fruition as she had hoped, leaving her as the sole caregiver for her ailing mother. Full-time caregiving takes an emotional toll, as she learned firsthand.

“My mother became the sole caretaker,” says Kalani. “She put her marriage on hold. She literally put her life on hold.” Caregiving tasks also took a physical toll. “My grandmother is a short, petite little lady, but the effects of Alzheimer’s took away her mobility. I watched her deteriorate. She cannot stand on her own or talk any longer.” She was dead weight as Pua tried to take care of her physical needs of daily living and support her mother in every way possible, as she promised her father she would.

Long-Distance Caregiving

Lu now lives at the Life Care Center in Hilo. Pua and Kalani visited her often in person before the COVID-19 pandemic exerted its overpowering grip on the world. Now, the families of those in long-term medical facilities must comply with health mandates for the safety of all concerned. Families now provide long-distance caregiving by communicating with their loved ones through internet meeting programs on tablets, computers and smartphones.

“We used to bring her flowers and candy and chocolate ice cream,” says Kalani. “Oh how that tiny Filipino- Hawaiian woman loves her sweets! My mom also dropped off my albums. Caregivers at the center play them for her and I could see in the videos they sent us that she would wander. Since she can not articulate, her eyes tell the story. As she connects with the music, her eyes tell me that she loves me and she is proud of me.”

In 2013, Kalani and his partner moved to Maui. Pua came to live with them years later. Kalani transferred from the Big Island as a teacher and Hawaiian resource coordinator at Kamehameha Schools. He left that position after 10 years to pursue his dreams full-time as a musician and educator. He conducts workshops on Hawaiian music composition and songwriting while he is touring. He donates a portion of his concert proceeds to the Alzheimer’s Association to honor his grandmother.

In 2013, Kalani and his partner moved to Maui. Pua came to live with them years later. Kalani transferred from the Big Island as a teacher and Hawaiian resource coordinator at Kamehameha Schools. He left that position after 10 years to pursue his dreams full-time as a musician and educator. He conducts workshops on Hawaiian music composition and songwriting while he is touring. He donates a portion of his concert proceeds to the Alzheimer’s Association to honor his grandmother.

After years of solo caregiving, fighting feelings of failure and defeat, Pua moved to beautiful Maui to live with Kalani and his partner. Mama was moved to the Life Care Center.

“I want to emphasize that caregivers should take care of themselves,” says Kalani. “Mālama their piko — all of their temples — and spiritually heal. Ask for help for a good hour or two a day so you can take care of yourself and find time to heal so you can take care of others, as well. You can’t do it all.”

“Mom didn’t get that,” says Kalani. So he told his mother, “Come holomua in Maui. Come and heal. I will take care of you. If you are not going to take care of yourself, I’m going to lose you first before I lose my grandma.”

“It was a fight for me with my siblings,” Pua says. “But my mother taught me the meaning of the word forgiveness. With that, you allow reopening of a new chapter in your life. You allow acceptance because God is going to take care of you. My mother is a woman of faith. She is my light. She lights the way when I feel I am in darkness.”

“So I kissed Mama goodbye, telling her I have to leave,” says Pua. “And although she could not articulate her thoughts and feelings, the look in her eyes told me ‘All is well.’”

“Mama continues to shine even over this distance that separates us,” says Pua. They often connect through internet video. “As soon as she is able to tell where the voices are coming from, she looks right at the screen — right at us.” Pua also sends regular care packages. The social workers at the center are very helpful maintaining whatever connection is possible with her mother. “God is ensuring I connect with her no matter what.”

“I just came back from visiting her before the quarantine. Hurricane Douglas had just passed. I told myself I just had to go,” says Pua. “Mama is on the third floor of the facility. They sit her next to the window and I talk to her outside from the ground floor. She hears my voice and looks right at me. Our spirits connect.”

“I think Mama wants us to accept the fact that she is going to go,” says Kalani. “We are okay with her going to leave, but she is such a strong woman… to have this horrendous disease for 10 years when many last only five or six years before they succumb to the disease.”

“She is fighting it, but I think she wants our family to ho‘oponopono,” the Hawaiian practice of reconciliation and forgiveness, “and holomua” [improve],” says Kalani.

“Values play such an important role in our ‘ohana, …understanding the values of forgiveness and having the trait of being a good person who is good to people,” says Kalani.

Kalani spoke of friends who were very secretive and ashamed regarding their loved ones with dementia and Alzheimer’s. Kalani’s advice: “Don’t be ashamed to talk about it. People will talk about their loved ones with cancer or diabetes or whatever, but this particular disease — Alzheimer’s — is also something to talk about. It’s okay to talk about your mom forgetting things. It’s okay to talk about your mom forgetting your name. It’s okay to talk about her hitting you during sundowners because she can’t control her anger. Just don’t be hard on her or him… Love them, hold them, tell them it’s okay. Just understand that they can’t control their behavior. They can’t control their delusions.”

He reports that those friends who took his advice are very grateful that he shared his own experiences with them.

“There is a stigma,” says Kalani. “People are afraid and ashamed. So it is helpful for us to create and share this dialogue and diary with other people who are new to this. It’s okay to talk about the issues to help educate other caregivers and to let them know they are not alone.”

Before COVID, Kalani would whisper in his Mama’s ear, continually reminding her of how much he loves her. He would also sing to her. “I brought her flowers and chocolates on her birthday,” says Kalani. “She did not recognize me for a while until I sang to her and told her who I was. I was able to connect with her through my music for a split second. I sang her favorite song, Blue Darling. My grandfather would sing that song to her when they would argue. She sang along with me. And then she kissed me. ‘I love you, Ara,’” she said. “She calls me Ara for short.”

A video of this bittersweet exchange went viral last November.

“She always supported my educational endeavors,” says Kalani. “She was always in the front row watching me perform. She was at the forefront of all my performances.” Now she rarely recognizes Ara. “That breaks my heart,” he says.

“She always supported my educational endeavors,” says Kalani. “She was always in the front row watching me perform. She was at the forefront of all my performances.” Now she rarely recognizes Ara. “That breaks my heart,” he says.

“But that moment, at that time… I had her… for less that a minute, but I had her,” he said. “She knew exactly who I was. That was a moment I had her, vividly, looking at me in my eye. I could see in her eyes how much she loved me.” Kalani touched his heart and inhaled deeply at the recollection of that precious moment.

“I didn’t know she would totally remember a song and remember me through song,” says Kalani. “And I realized how music brings healing to the heart and the soul and to the mind. Music is so essential; it plays such an important role. I think music is among our antidotes and medicines for the elderly. Whether there are workshops through the Alzheimer’s Association or through caregivers out there, music and dance should be imbedded in a system for our kūpuna. Music allows you reflect on the past and allows our elderly to really connect with their loved ones.”

“I still cry every time I visit her because I know she is deteriorating,” says Kalani. “I know I am losing her verbally, mentally… all of that. But the music allows me to link with her spiritually. I knew that was the strongest medicine I could have given her. And at that specific time and place of deep connection, you can’t replace that moment.”

Kalani also said that despite her forgetfulness, Lu was able to recite her prayers without hesitation, underscoring her strong spiritual connection.

While there’s no cure for Alzheimer’s, music has been shown to have emotional and behavioral benefits for those living with the disease. Kalani and Mama continue to have rare instances of connection through his music, but the frequency has dissipated over time as the disease progresses.

A Musical Heritage

“My whole family sings,” says Kalani. “My paternal grandfather, John Pe‘a, who passed away from Alzheimer’s, was an opera singer. My dad plays the bass. My mom’s family were musicians, too. I come from a line of musicians but I was the first to record an actual album that talks about people I love, places I love in Hawai‘i, people who have affected me my whole life… and that is all through songwriting and personal experiences. I didn’t win accolades overnight… I prepared and trained. The accolades do not define who I am. It is my parents — my mom — who taught me to be proud of who I am as a kanaka and to be good to people. My grandmother always taught us that being good to people is the best trait you could have.

Kalani says he owes his musical career to his mother and his ancestors. He shared that he stuttered as a keiki and what helped him overcome the impediment was music. “My parents put me in choirs, music theory classes, ear training, and piano and guitar lessons.”

He said his mom put him in oversized suits and encouraged him to sing at weddings and charity events. “But I never thought I would do music full-time because full-time musicians don’t make any money at all,” Kalani says. “I’m not becoming a teacher either, flying chalk at kids. But I became a teacher, creating Hawaiian culture curriculum, and using my music skills and proficiencies, I have created STEM curricula.”

Music Curriculum for Kūpuna

“I have talked to Alzheimer’s Association Executive Director LJ Duenas and the team at the Aloha Chapter about building a curriculum for our kūpuna,” says Kalani. “I want to contribute that because I believe that music plays a role with our kūpuna. I believe that music should be implemented in their care programs and I am there to assist. The Alzheimer’s Association is my number one charity because of my kūpuna.”

Kalani’s late paternal grandparents also suffered from this disease. “This disease truly runs through he veins of my family.”

The Water of Life

Waiwai means value, wealth or knowledge. Wai means water; water is wealth. “Water is a medicine that keeps us alive and well,” says Kalani.

Na Wai Eha in West Maui — The Four Great Waters, a place of Nā Akua — is a system of fresh water streams that sustained thriving Hawaiian communities since time immemorial. Part of the system includes Wailuku Stream (‘Īao Stream).

“The stream symbolizes the cycle of energy and life,” Kalani says. “Similarly, our kūpuna and those before them had this wealth of knowledge and wisdom that they bestowed upon us to continue their legacies and our heritage, whether we speak the language, dance hula, or learn our history and genealogy. They teach us to be comfortable with our identity and ourselves and remember who we are and where we come from.”

“That stream talks about the connectivity of life,” says Kalani. “If we are going through trials and tribulations, we are rejuvenating ourselves with water given by God so we grow and be strong and be good people. And we all need to be good people of compassion, especially now.”

It is one of the places we have a spiritual connection with our ancestors,” says Kalani. “The water of life flows through us from our kūpuna. The stream that flows consistently from mountain to ocean is symbolic and metaphoric of this human cycle. As water is our waiwai, our kūpuna are our waiwai.”

“I often wake up and wish this was just a terrible nightmare and I could just pick up my phone and call her and tell her how much I love her,” says Kalani. “I wish I could fly to the house she once owned and see her purple orchids… I wish I could just grab her and tell her how much I love her. It is really hard to understand this disease. I wish I could be in the shoes of a person with Alzheimer’s and feel what they feel… what is holding them back, what they are thinking.” Kalani sighs. “I miss her so much. I do.”

The Color Purple

When Kalani would perform Kahunani No ‘Ō la‘a, the song he wrote for his grandmother that was recorded on his Grammy Award-winning sophomore album, No ‘Ane‘i, some audience members would make the connection to their loved ones who have faced Alzheimer’s or who have passed away from the disease. Kalani and his mother, Pua, were honored to share their experiences. And ultimately after his performances, they would ask him about his signature purple clothing. He expresses his deep connection to his ancestors through symbolism in both song and color. Kalani means “the heavenly skies.” He is named after his father, Arthur Kalani Pe‘a. “The sky is blue. The koko, the blood of God, Jesus Christ, is red. When you combine both colors, you have purple! It is my connection to the spiritual world and reconnecting with my kūpuna. It is they who paved the path for me. They have nurtured me and raised me to be the man I am today.” Kalani Pe‘a embodies the understated confidence of one who knows he is much loved. He is very good to people.

Leave a Reply