Following his inner guiding star, Kimokeo skillfully navigates the subterranean waters of his own inner world and kuleana.

In the Hawaiian tradition, the purpose of life —the meaning of our being here on Earth — is to fulfill a unique responsibility, our kuleana. This traditional way of looking at human existence addresses the age-old questions about the meaning of life, while grounding it in everyday practically. It invites each of us to reflect upon what our purpose may be — and how best to offer our gifts, talents and strengths to the world, intentionally and powerfully, for the enrichment of all beings.

Living among us in these modern times are Hawaiian elders whose kuleana is to share Native Hawaiian core values with future generations. In doing so, they ensure that traditional beliefs, such as kuleana, find new relevance in our modern-day world.

Kimokeo Kapahulehua, 64, is one of Hawai‘i’s wisdom keepers. (His surname refers to the sound of lehua branches rubbing against each other in the wind.) He is a kūpuna (elder) with extraordinary knowledge of the land and its people. As a pillar in the Maui community, he makes an incredible effort to address a vast number of issues — from engaging youth groups and restoring ancient fishponds, to tirelessly working toward land preservation and the eradication of invasive species.

Yet, Kimokeo didn’t always know his kuleana. Like most of us, he discovered it along his life’s journey.

As a precocious child he was a fast learner and a bit of a daredevil. He was very much a “doer” … much to the consternation of his parents, who often feared for his safety.

With the boundless mana (energy) of his robust nature, he was branded with the nickname “Bully,” as his parents viewed their super-active, chubby child as a kind of free-ranging bull. He was an intensely focused fireball of a child, typically engaged in the unrestrained pursuit of whatever claimed his attention.

Stories abound of how the clever boy managed to stow away on late night fishing forays that only adults were permitted to join and sought out his own superior, fishing spots. Even his grandfather, then chief of police, could not reel him in.

In his adolescence, he became the “King Kong” of Kaua‘i beaches, challenging the biggest waves — the more dangerous the better — on his primitive, wooden surfboard. At the age of 12, he discovered outrigger canoe paddling and participated in his first canoe race at age 14.

As an instinctive waterman, Kimokeo related to Kanaloa, the Hawaiian god of the ocean. He connected with idea that a fully lived life as a Hawaiian demands experience in and of the water. To become a complete person, he knew he must commune, profoundly and passionately, with the sea.

His bond to the ocean followed him into adulthood and later became a defining element of his kuleana.

Passion Finds A Practical Focus

As he matured, an awareness of his life mission, or kuleana, began to crystallize. Something quite different lay ahead for him. His penchant for taking on risky challenges, separating from others and “winning” began to morph into a new, more benevolent kind of passion. He began to choose to give generously from his deep well of aloha (love energy) and serve as a mentor. He would become a dynamic, endlessly renewable source of kōkua (benevolent assistance) whose undeterred giving of his best self would shine forth into the world, personifying the Hawaiian principles of pono (doing what is right, in the fullest sense) and ma¯lama (taking good care of all that’s precious).

In the pidgin expression, “If can, can; if no can, no can,” he would have emphatic use for the first half of that affirmation only: If can, CAN!

His Uncle Kawika, who had sailed on the famed Hōkūle’a to Tahiti in 1976, challenged him to “connect all of the Hawaiian Islands like a flower lei.” Historically, this would be a re-enactment of King Kamehameha II’s feat, only this time it would be a deliberate mission of peace.

His Uncle Kawika, who had sailed on the famed Hōkūle’a to Tahiti in 1976, challenged him to “connect all of the Hawaiian Islands like a flower lei.” Historically, this would be a re-enactment of King Kamehameha II’s feat, only this time it would be a deliberate mission of peace.

Recognizing and accepting this as his responsibility (kuleana) to his family — and seeing it, too, as an extension of his commitment to perpetuate the Hawaiian culture — Kimokeo began a series of open-ocean canoe voyages in 2002 that traversed all the inter-island Hawaiian channels.

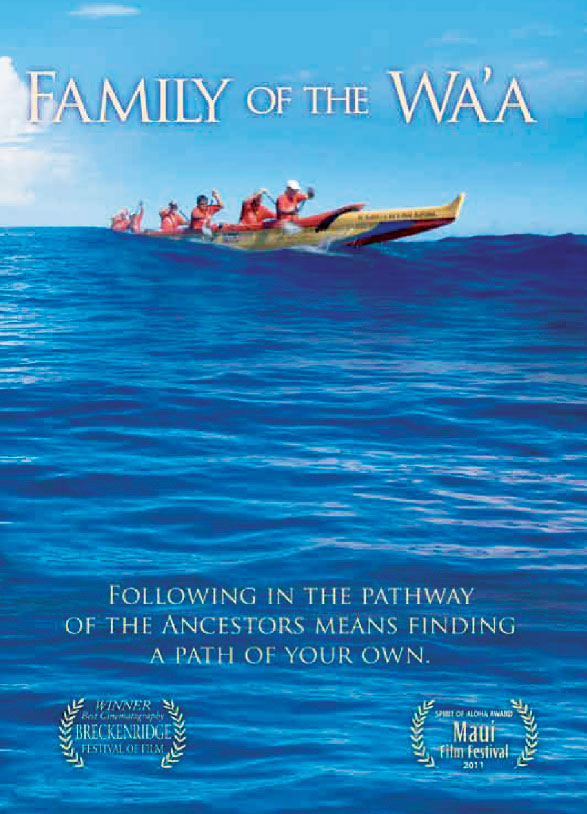

On these journeys, he was mostly accompanied by rock-star-quality crews; but, true to his all-embracing nature, he also chose to include recreational novices in their 60s. The series of voyages culminated in 2008 in an epic, 400-mile paddle from Laysan to Kure Atoll in the Northwest Hawaiian Island chain. It became the subject of a recent film directed by Alyssa Fedele, “The Family of the Wa’a.” (familyofthewaa.com).

The lei connecting the Islands was finally complete, and Uncle Kawika’s vision accomplished. The entire Hawaiian archipelago had been bridged. The Islands, considered by Hawaiians to be sentient, living beings, could now rejoice in the reappearance of canoes into their remote worlds. Even distant Kure had now “seen” the coming again of the wa‘a, the living canoe, upon her waters.

By the mid-1990s, Kimokeo met Kumu Keli‘i Tau‘a, a modern Hawaiian like himself whose passion for Hawaiian culture, chant and protocol would raise his passion for canoe paddling to a higher octave. His life would be forever changed by the synergy and magic of that meeting.

The coming together of these two great Hawaiian men — one a waterman, the other a kumu hula (teacher)—formed the perfect partnership. It would ignite them both and offer “Bully” a new name — Kimokeo. He also had an evolved and awakened view of his own calling… he would become an educator, a whirring hub of community action and goodwill, offering his unique mana to everyone who cared to receive it. Once “born to be wild,” he had now become“re-born, to willingly share.”

In this newfound capacity as harmonizer, he blurred the boundaries between kanaka maole and haole. In Kimokeo’s view, native people and foreigners were “all one team.” Transcending prejudice, he spread his attention across all demographics — young and old, able-bodied and “adaptive,” native and newcomer.

Assuming the Mantle of Cultural Leader — a Kahu

In 2003, under the spiritual mentoring of Kumu Tau‘a, Kimokeo formed a cultural hālau, Maui Nui O Kama, and became its alaka‘i (leader). The hālau was an instrument in educating the public and in introducing Hawaiian ceremony to special occasions. The hālau became extraordinarily active in supporting families through rites of passage, such as the death of loved ones, and blessing homes, businesses, nature centers, roadways, hospitals, sports events and even film directors. Almost 10 years later, the hālau continues to be sought out and appreciated by many who’ve been touched by its ceremonies. Its members, predominantly non-Hawaiian, have become genuine practitioners of Hawaiian culture — with a legitimacy that only Kimokeo’s vision and attentive leadership could have bestowed.

Kimokeo would also help restore lo‘i (taro fields) at Honokahau, Maui, and on land stewarded by Kawehi Ryder (brother of Hawaiian spiritual practitioner, Lei‘ohu Ryder) on La¯na‘i. He would direct the restoration of Ko‘ie‘ie, an ancient fishpond in the Ka‘ono‘ulu Ahupua‘a on Maui, by enlisting the help of the Native Hawaiian community, residents and visitors. His directive to all was simply to participate: “Carry at least one pōhaku (stone) into place.”

Kimokeo would also inspire cancer survivors (the so-called Mana‘olana “Pink Paddlers”) to accomplish things they’d never dared to dream, leading them on life-affirming paddles across wild, open ocean. He would even introduce adaptive (physically and emotionally challenged) paddlers to canoe racing, super-charging their self-esteem.

Forever a champion of the younger generation, Kimokeo was for several years director of the Kīhei Youth Center. And he continues to spearhead several fundraisers on its behalf. At a recent fundraiser to support teens participating in the 2012 World Sprints in Canada, he not only led the opening prayer and served as master of ceremonies, he also stepped up as an impromptu auctioneer to bump up the bid on an auction item that he felt was selling too low.

Under Kimokeo’s tutelage, hundreds of youngsters have found a passion for canoe racing. Indeed, introducing the younger generation to a pono, drug-free lifestyle has always been one of his major initiatives.

Hālau members Bud and Dottie Nykaza have had a special window on Kimokeo’s depth, versatility and seemingly boundless energy. Since the hālau’s inception, they have served—like a pair of extra heads and two pairs of extra arms and hands — as Kimokeo’s willing assistants, often on call day and night.

Bud, a 60-something recreational paddler and ace steersman on inter-island voyages, sees the tenderness underlying Kimokeo’s actions: “He’s comfortable enough with himself to show emotions publicly … never ashamed to shed tears,” Bud says. “Ever since I met him, I’ve felt a connection with him, the way a son would feel toward his father. He’s always watching out for my safety. His way is no drama, no hesitation …just results!”

Modern Hawaiians such as Kimokeo and Kumu Tau’a, who walk the walk — steadily and devotedly — and talk no more than necessary to get the job done are our mentors and wayshowers, our living examples of what’s truly pono.

Kimokeo notes that as we age and mature, our kuleana may also change. In fact, a quality of ma¯lie (calmness and steadiness) typically increases as you age. Ma¯lie can sometimes make it possible for elders to achieve goals that eluded them when they were younger and more harried.

Regardless of your age, it’s important to ask yourself, What is your kuleana? What is your responsibility, or role in life? What can you accomplish today that perhaps got away from you yesterday? And, how are you going to express your kuleana? What will it “look” like in practical, everyday life? And, perhaps most importantly, how will you share it and how may it benefit others?

Leave a Reply