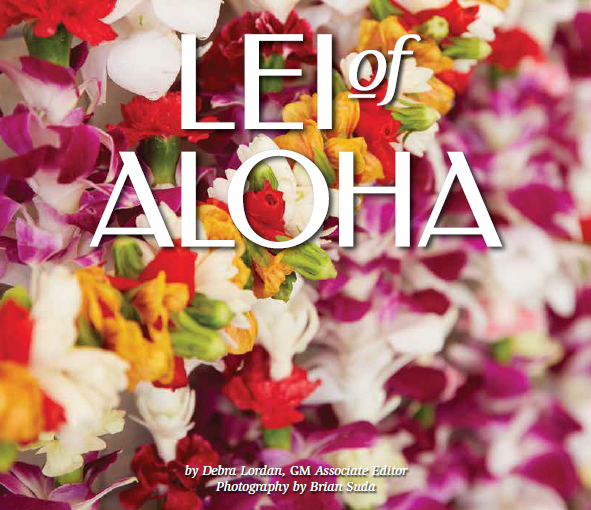

In Hawai‘i, any occasion can be made more special by the giving of a lei. Whether it’s for love, a celebration or to honor someone, you can choose the one that symbolizes the sentiment you want to convey or select the one that suits your taste. All represent the rich heritage of the lei.

In Hawai‘i, any occasion can be made more special by the giving of a lei. Whether it’s for love, a celebration or to honor someone, you can choose the one that symbolizes the sentiment you want to convey or select the one that suits your taste. All represent the rich heritage of the lei.

Lei Day, May 1, is dedicated to the Hawaiian tradition of making and giving lei. But some may not know the the tradition entails much more than the officially dedicated day. The traditions that surround lei make them appropriate for many occasions. Hawaiian tradition also offers particular lei for celebrations and seasonal events.

Giving a lei symbolizes friendship, love, respect and honor. It is a gift for greeting someone warmly. It represents the spirit of aloha. Its beauty and meaning flow from the heart of the giver.

A Hawaiian Tradition

The tradition of adorning themselves with wreaths of local vines and flowers to honor their gods came to Hawai‘i with the Polynesians who settled here long ago. They brought with them many of the plants they needed for daily life — plants for medicinal use, plants for food and plants that they brought for their sweet scent for use as a personal embellishment.

In their new island home, lei came to signify royalty, rank, status and wealth. The geography of the area, the religion of its people and the tradition of the hula were all associated with the lei they wore. As time passed, they developed their own unique culture and traditions.

The new Native Hawaiians found many other items, including hala and maile, that could be fashioned into adornments. In Old Hawai‘i, lei were created with the lush flowers, vines and leaf stems of every kind from every island — even seaweed from the rich Hawaiian waters. Lei were also made with ivory, bone, seeds, kukui nuts, hair, teeth, shells and feathers.

The pupu lei was made from shells and the hulu manu lei was made from feathers. Niho palaoa lei were made of the bones of the walrus and whale held together by human hair, which were passed down through generations.

Other plants and materials were introduced later, such as the carnation, orchid and plumeria.

Lei and Hula

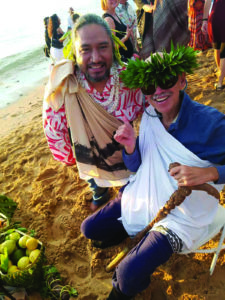

What Kapono Kamaunu knows about lei and Hawaiian culture, he didn’t learn growing up. He was raised on O‘ahu, where his childhood activities and interests mostly revolved around Waikīkī Beach and sports. When he moved to Maui in 1993, he met Kumu Hula Keli‘i Tau‘ā, a teacher at Baldwin High School. As a freshman, he not only learned about hula and chanting, but other aspects of the Hawaiian culture, as well.

Kapono and his wife, Priscilla, became kumu hula 10 years later, offering training for hālau hula on Zoom since the pandemic began. They own and run a home-based hula implement-making business called “Na Kani O Hula.” Kapono works as a cultural advisor at the Fairmont Kealani and performs at the Old Lāhainā Lū‘au, as well.

“Through hula, we learned about lei-making, Hawaiian history and culture,” he says.

In Old Hawai‘i, the major types of lei were each related to different spirits and used for different reasons. Many were related to Hawaiian myths and religious customs, Kapono says.

“It goes back to hula,” says Kapono. “For most of the year, the lives of the Hawaiian people were strictly governed by a set of laws called ‘kapu.’ Everything they did was directed by these kapu, including hula. But during the Makahiki season (October or November through February or March), the ancient Hawaiian New Year festival in honor of Lono, many kapu were suspended. This time of year, kane (men) were allowed to perform hula on heiau, traditional religious temples. Makahiki was a time of peace, gathering and hula performances without restriction. For ceremonial purposes, hula dancers would wear lei.”

“It goes back to hula,” says Kapono. “For most of the year, the lives of the Hawaiian people were strictly governed by a set of laws called ‘kapu.’ Everything they did was directed by these kapu, including hula. But during the Makahiki season (October or November through February or March), the ancient Hawaiian New Year festival in honor of Lono, many kapu were suspended. This time of year, kane (men) were allowed to perform hula on heiau, traditional religious temples. Makahiki was a time of peace, gathering and hula performances without restriction. For ceremonial purposes, hula dancers would wear lei.”

Traditionally, hula dancers wear specific lei to reflect the dance they are performing, especially in a competition setting. Dancers tie in the story — the chant or mo‘ōlelo — its setting and the flowers, ferns and other materials found in the location relevant to the story, says Kapono.

“In hula, we say kinolau — the divine is everywhere, and everything is the divine. It is the physical embodiment of the many Hawaiian gods and goddesses.”

“After asking permission from Laka first, hula dancers would gather ferns, such as palapalai, laua‘e ferns and maile, for their adornments in ceremonial performances and other practices as well,” says Kapono. “The gathered vines, leaves or flowers were placed on the kuahu hula (hula altar) dedicated to Laka.”

“Whatever is in the song, we aim for the closest possible representation.”

“For example, Pele and her sister Hi‘iaka are represented by the red flowers of the ‘ohi‘a lehua brought to the islands by the Polynesians settlers. So when you do a dance about Pele, you would wear a haku (braided) lei or a lei po‘o made of ‘ohi‘a lehua, as well as a lei a‘i (a neck lei).”

Traditional Meanings and Uses of Lei

One of the most popular of all the lei varieties was the maile lei, made from a leaf-covered vine with a sweet and spicy scent. This vine was worn around the neck, draping freely down to the waist. The maile lei was related to the spirit of the hula dance and represented Laka, the goddess of hula, as well as other sacred spirits.

For chieftains and members of royalty, the ilima was preferred. The full, lush lei was made from hundreds of delicate orange blossoms.

The ti plant has a long tradition of being planted outside homes to keep evil spirits away. Ti stalks were used to proclaim peace and to call a truce. A lei was made by tying ti leaves together. The open lei was worn by physicians and priests.

Limu kala, a type of seaweed, was gathered and used in many different ways — for religious purposes, as medicine, for consumption or as a lei. Traditionally, limu kala was gathering, fashioned into a lei and worn by a person suffering from an illness. The ill person or a kahuna would then pray to Kanaloa. When prayers were completed, the wearer of the lei would fully immerse him or herself in the ocean. In time, the lei would be swept into the sea as an offering to Kanaloa, in hopes of cleansing the wearer of the aliment.

Lei Traditions of Yesterday and Today

By fusing their island lifestyle with their sacred rituals and the natural elements around them, Hawaiians created lei that began to be worn for virtually every occasion by both commoners (maka‘ainānā) and chiefs (ali‘i) alike.

“Today, lei are used for an array of occasions and it is widely accepted throughout Hawai‘i Nei that any type of lei can be worn by anyone and everyone,” says Kapono. “One thing that hasn’t changed is that the giving of a lei symbolizes giving your mana to someone else.”

Mana is a supernatural force that may be ascribed to persons, spirits or inanimate objects. It may be good or evil; beneficial or dangerous.

“When we are making lei, we want to ensure that we are putting the best of our spiritual energy into the lei,” says Kapono, “so when we give it to someone, we are giving them good energy, connection and love. Lei are the quintessential symbol

of love; of aloha.”

The type of flower made into a lei and gifted to a loved one has more to do with personal preference and seasonal availability than symbolism, says Kapono.

Although the lei of today are much like those worn in Old Hawai‘i when the first Polynesians settled the islands, their meaning and presentation has changed over the years.

Lei in Old Hawai‘i symbolized the status of the wearer and were presented by bowing and holding out the lei for the recipient to take.

“Traditionally, it was disrespectful to drape a lei over a person’s head, particularly when that someone was royalty,” says Kapono. “You do not want someone to interfere with your connection to Akua by having them cut off your mana.” This presentation method gave the recipient the option of taking it and putting it on themselves, giving it away, putting it on an altar or taking it to the ocean. “Because, just as lei are made and presented with love, they can also have bad intentions.”

Around the 1840s, when Steamer Days or Boat Days began at Aloha Tower and Honolulu Harbor, visitors were greeted with armloads of lei. It may have been at this time that lei began to be placed over the heads of those arriving or departing, accompanied by a kiss on the cheek. That particular tradition came to a halt with the arrival of jet planes in the 1950s. To accommodate visitors, Daniel K. Inouye International Airport’s lei stands are located in the area.

Although most islanders believe that anyone can wear any type of lei for any occasion, Hawaiian tradition dictates the use of specific lei that are symbolic of the occasion, related to the season and dependent on the time of year the flower is in bloom. Worn at other times, it can bring the wearer bad luck.

For example, a lei made from the yellow, orange and red keys of the pineapple-like hala fruit interlaced with maile leaf or laua‘e fern can be worn at the beginning of Makahiki season, the Hawaiian New Year. Worn at this time, the hala lei invites good luck, pushes bad luck aside and prompts the wearer to forgive past grudges. However, worn at other times of the year, it can bring the wearer bad luck. The lei is associated with death and is often worn at funerals.

Although there is significant meaning associated with the giving of a lei, it is open to different interpretations by the maker, seller, giver or recipient. But it may be wise to be aware of certain traditional details.

“Some people still believe that it is inappropriate to give a pregnant woman a closed lei,” says Kapono. “An open lei may be given, as it symbolizes that the baby will be unencumbered and unharmed by the umbilical cord, ensuring it will not be tangled around its neck in the womb.”

Lei are often referenced as being created in a circle to symbolize love and the family circle. “Lei, like many of our nāmea Hawai‘i (Hawaiian arts), have grown and evolved into priceless artifacts that are shared around the world. Whether it’s an heirloom feather lei, a lei pupu that is passed down from generation to generation, or lei made from fragrant flowers and beautiful ferns, the joy of gifting and receiving a lei filled with the aloha spirit can brighten anyone’s day — even during the darkest of times.”

A Family Tradition: Love From the Lei-Sellers

“That is what we have to offer in this pandemic — love. I know that when people receive lei, they feel the love we put into them,” says Ku‘ulei Ka‘ae, who makes and sells lei from her stand near Daniel K. Inouye International Airport. “I don’t think a lot of people realize what a lei can do for a person. The type of lei you give is a personal choice. Whether it is pikake, plumeria, ginger, pakalana or double tuberose, the giver must love the flower as it is a symbol and extension of their love for the recipient.”

Ku‘ulei’s family began selling lei four generations ago, beginning with her great-grandparents. They sold in different locations, such as Chinatown and Aloha Tower. Their daughter, Sophia Ventura, Ku‘ulei’s grandmother, had a 1932 Ford truck that her husband equipped with hooks for displaying the lei. She also sold lei at Fort DeRussy — the only lei seller there. She was later invited to set up shop near the access road of the then Aeronautics Aviation Airport.

Ku‘ulei was around 9 when the stands moved to Lagoon Drive in 1963. “My mother and I were the first ones to open our doors in this new building.” In the early 1990s, they were relocated to the concrete building they now occupy.

The women selling lei at this location are descendants of the original Native Hawaiian airport lei sellers. Since Ku‘ulei is the only daughter in her family, her mother gave her Pua Melia, the Airport Lei Stand she operates to this day.

“The only time I ever got a lei growing up was when my mom brought home a plumeria lei for May Day. I wondered, why a plumeria? I asked my mom why I couldn’t have a double carnation lei or pikake. She said, ‘Because the plumeria is the most beautiful flower. One day you will understand.’ The point was, when you get a lei, it is from the heart. It is aloha; it is love. When you are younger, you don’t really understand the depth and meaning.”

“Then when I was in ninth grade, she brought me a double carnation. I was so thrilled! When I went to school, I put it on. I took it off about a half-hour later and gave it to a friend because I realized it didn’t mean anything to me. It wasn’t from my mother’s heart. She only got it for me because I asked for it. Oh how I wished I had that plumeria lei — it meant the world to me! I realized what my mother was saying. The most beautiful lei comes from the heart.”

“I will wear your love as a lei,” Ku‘ulei recited in Hawaiian.”

Hawai‘i’s lei have become revered all over the world for their beauty and fragrance. “Today, many lei or hula practitioners teach the traditional art and practices of lei, continuing to strengthen our heritage through our younger generation, visitors and practitioners abroad so we can wrap a lei of peace and aloha around the entire world,” says Kapono.

Leave a Reply