So was the faith of one Hawaiian youth who fled tragedy in 1810 and wound up in Connecticut, where he found consolation and forgiveness in the God of Jacob. His name was Henry ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia. The seed of his faith brought Christianity to Hawai‘i in 1820.

So was the faith of one Hawaiian youth who fled tragedy in 1810 and wound up in Connecticut, where he found consolation and forgiveness in the God of Jacob. His name was Henry ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia. The seed of his faith brought Christianity to Hawai‘i in 1820.

In his epic historical novel Hawai‘i, James A. Michener created fallible heroes and villains who have lived in our memories for over 60 years now. But when the missionaries are interpreted in the norms of their times, the tenets of their beliefs, we see their abiding faith to bring the gospel of peace to Henry Ōpūkaha‘ia’s people. The fruits of their labor persist, and in 2020, we celebrate 200 years of teaching God’s word and singing sacred hymns that inspire faith, hope and love.

Today, Kawaiaha‘o Church is pastored by Rev. Kenneth Makuakāne, who says, “God has worked in so many hearts and lives over the past 200 years and we are so proud that Kawaiaha‘o Church has been instrumental to the growth of the Christian faith here in Hawai‘i. The bicentennial is a good opportunity to reflect and better understand the relationships between the ali‘i, maka‘āina and missionaries.”

Carrying a Seed of Faith to Kawaiaha‘o

Carrying a Seed of Faith to Kawaiaha‘o

To understand what has been accomplished here, we go back to Kawaiaha‘o in King Kamehameha’s kingdom. It was an ‘ili land section of the Mānoa ahupua‘a and the name of a watering hole and spring on the dry plain above Waikīkī. Legend says a chieftess named Ha‘o liked to bathe here. In April of

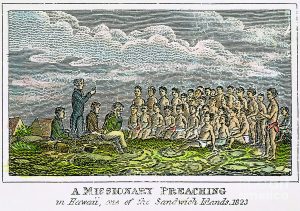

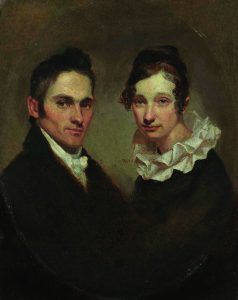

1820, when young newlyweds Hiram and Sybil Bingham arrived in Honolulu with the first company of missionaries from the American Board of Commission for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) on the brig Thaddeus, the ali‘i allowed them to stay and build a hale at Kawaiaha‘o spring.

They endured a five-month voyage that left Boston in October 1819, sailing down the Atlantic coast of the Americas to Cape Horn and then northwesterly across the open Pacific to the Sandwich Islands. Seven missionary couples included four ministers, a farmer, a doctor and a printer. Their four young Hawaiian companions were returning home from New England, where they ended up after working on trading ships: William Kanui, Thomas Hopu, John Honoli‘i and George Kaumuali‘i, a son of the King of Kaua‘i. Missing was Heneri (Henry) ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia, who died of typhus fever in 1818 at age 26, without seeing his beloved homeland again.

When Henry was 10, a raiding chief killed his parents. The chief threw a spear at Henry, who was fleeing with his 3-month-old brother on his back. The spear killed the baby and spared Henry. He was taken in by the man who killed his parents, but ran away to his uncle, the kahuna at Hiki‘au heiau in Kailua. There he began training to care take the temple, but his grief led to despair. Soon, he talked a ship’s captain into taking him away from Hawai‘i. The boy, who carried the name “gutted belly,” left for the sea at the age of 16 and ultimately landed New Haven, Conn., living in the home of the cousin of the head of the Yale Christian seminary.

Hea Iesū Ia Kākou La

(Jesus Calls O’er the Tumult)

Until about 1816, Christians believed that underdeveloped peoples without written language were not able to receive the “Word of God” because they could not read the scriptures themselves. A tenet of “freedom of Christ” championed by Martin Luther during the Reformation was that God speaks directly to the individual through the Bible, prayer, circumstance and conscience. But Henry, and a few other Hawaiians and Native Americans, were learning to speak English! Henry’s academic aptitude became the flash point for the founding of the first Foreign Mission School in 1816.

His culture’s oral tradition taught Henry ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia to listen carefully and memorize large amounts of data. This avid learner read scripture and chose Jesus Christ as his savior. The seed of his faith grew and he passionately lobbied that the gospel should be preached to his people in Hawai‘i. After his untimely death, his memoir was published by Edwing Dwight and sold to support the Hawaiian mission.

Passengers on the Thaddeus expected to find the Hawai‘i Henry left: raiding warriors killing children and adults, chaos and depravity, human sacrifice to the gods. They came to face hell — to share the good news of peace with God at the expense of their very lives.

Instead, in March 1820, as they sailed along West Hawai‘i toward Kawaihae, High Chief Kalanimoku and his wives approached in their double-hull canoes. But it was not a raid; it was their custom to greet all arriving ships to determine where they hailed from and what their intention might be. As the welcoming party paddled off, surprised and thankful Revs. Bingham and Thurston climbed up the rigging and joyfully serenaded them with a hymn.

After uniting the islands, Kamehameha the Great reigned in peace, outlawed ambushing and murder of travelers, and refused human sacrifices when he was sick and dying. He passed away in May 1819. The kapu system was customarily suspended to mourn his passing. When the new king, Liholiho, Dowager Queen Keopuolani, Queen Regent Ka‘ahumanu and High Kahuna Hewahewa chose not to reinstate it, the old kapu religion of Pā‘ao and the Tahitians was gone. Before the Thaddeus arrived, the harsh kapu rules were lifted, large carved ki‘i of the old gods burned and heiau closed. Henry ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia would have been gratefully surprised to see Hawai‘i at peace.

The missionaries sought out King Liholiho for permission to live in Hawai‘i. After some days of consideration, the chiefs allowed Rev. Asa and Lucy Thurston to reside in a home in Kona. A few days later, Rev. Hiram and Sybil Bingham sailed on to O‘ahu, where they were permitted to build a thatched hale by a spring hole named Kawaiaha‘o. At the first Sunday worship services in their home, curious Hawaiians enjoyed curious foreign music and singing. Soon, Bingham was preaching God’s word three times a week in Hawaiian and once a week in English. Henry ‘Ōpūkaha‘ia’s Christian brothers and sisters were fulfilling his one dying wish.

When Kawaiaha‘o was growing and Ka‘ahumanu’s laws were enacted, Lāhainā was still the royal seat of government. The high chiefs all had residences in Honolulu, which had a protected port that Kamehameha I had developed for sandalwood trade with Canton and Macao. A small fort and canon protected the pier, storehouses and royal residences near the dock. Some whaling captains brought their ships and crews in for provisioning, but most preferred anchorage in Lāhainā Roads, where alcohol was prohibited.

An 1810 map shows footpaths along the Waikīkī plain connecting high chiefs with their lower chiefs and advisors. Behind the beach and dry plain, cooler farmlands reached up to the lush valleys of Mānoa and Nu‘uanu, where the nourishing waters of Kāne, the god of life and fresh water, flowed.

Pā Nahe Maila Kō Iesu Kāhea

(Softly and Tenderly, Jesus is Calling)

Each of the missionaries had responded to the personal call of God. The curious young newlyweds, 5,000 miles and three climate zones away from home, prayed that God would speak directly to the hearts of Native Hawaiians. To this end, they worked diligently to convey the holy scriptures in Hawaiian. Christians can demonstrate the love of God by their pious lives, but knowledge of the living and invisible God comes from reading what God says about Himself in the holy scriptures.

First, they captured all the sounds of spoken Hawaiian in an alphabet that could be used to phonetically write Hawaiian words. Soon, classes were offered to teach Hawaiians to write their own words on chalkboards. Writing letters became all the rage in 1825. By 1837, The Hawaiian Kingdom was the most literate nation on Earth. Literacy estimates were 90 percent — higher than Scotland’s at that time. Missionary printing presses furiously stamped out spelling books, hymnals, dictionaries and newspapers. The Hawaiian’s thirst for learning was unquenchable.

The next giant task was to translate the Bible, so Hawaiians could read and interpret the scriptures themselves. The Hebrew, Latin and Greek training that the missionaries received in seminary helped, and the ali‘i designated Native Hawaiian poets and scholars to assist in the translation process. The New Testament was translated by 1832; the Old Testament by 1839. The translators were surprised to find similarities between Hebrew and Hawaiian languages, which made translating the Old Testament easier than the new.

With reading and hearing the soft and tender call of the Lord, some high ali‘i accepted Christ, beginning with Queen Keopuolani in 1823, Queen Regent Ka‘ahumanu in 1824 and many more in the later 1920s. But the “Great Awakening,” a massive move of the Holy Spirit, didn’t start until 1837. Most of the smaller congregational churches were built between 1840 and 1860.

Iesū Ke Kumu o Kōna Ekalesia

(The Church’s One Foundation)

As an increasing number Native Hawaiians attended services, large thatch meeting houses were constructed at Kawaiaha‘o. The faithful walked miles to Sunday Sabbath meetings that lasted several hours and involved sharing hymns, lessons and meals.

Most of the missionaries kept detailed journals of their experiences. Titus Coan penned one of the earliest descriptions of a volcanic eruption and a flow that nearly reached Hilo. Hiram Bingham described services at Kawaiaha‘o Church, the translation work and the royal school for ali‘i children. Lucy Thurston wrote about her life in Kailua. When she found a lump in her breast, a physician operated to remove it as she lay on her kitchen table, comforted by God, whiskey and something hard to bite on. Her extreme faith and courage saved her life.

In 1827, Rev. Bingham reported to the ABCFM about a lovely garden tea party Mrs. William Richards from Waine‘e mission and her sister, Sybil Bingham, prepared for the ali‘i on the lawn at Kawaiaha‘o. King Liholiho and Ka‘ahumanu, with all the first- and second-rank high chiefs and several others connected to them through marriage, were on the guest list.

Rev. Bingham’ report read: “Twenty-one chiefs of the Sandwich Islands mingling in friendly, courteous and Christian conversation with seven of the mission family whom you have employed among them. Contemplate their former and their present hopes. They have laid aside their vices and excesses, their love of noise and war… the privileges they now enjoy, but you will hear these old warriors lamenting that their former kings, their fathers and their companions in arms had been slain in battle or carried off by the hand of time before the blessed Gospel of Christ had been proclaimed on these benighted shores.”

To celebrate the bicentennial, Kawaiaha‘o Church is holding another tea party on the church lawn — complete with cookies and cakes, fragrant tea and entertainment by the Puamana trio.

Sunday services at Kawaiaha‘o attracted thousands of people, a third of whom sang from their own copy of the hymn book, bound in hand-woven or cloth covers. Rev. Bingham admired their pleasing attention to scripture reading and preaching, “while angels wait to witness the effect of the word of God on their hearts.” His work to make the word of God available to Hawaiians was hard but very rewarding.

As the congregation grew, so did the church. The 1821 Kawaiaha‘o meeting hall was a thatched hale with glass windows, wooden doors and a pulpit, but the congregation sat on mats on the ground, as was the Hawaiian custom. Larger meeting halls were subsequently built to accommodate a Sabbath Day service for 3,000 or 4,000 attendees, and numerous reading and writing classes.

In 1838, Rev. Bingham planned and oversaw the beginning of construction for the novel “Stone Church,” as it came to be called, with a design based on the Goshen Congregational Church in Goshen, Conn., where he and Asa Thurston were ordained. The difference was that it was not built from any type of stone, brick or wood, but 14,000 slabs of inshore coral. Divers cut out each 1,000-pound slab with knives and teams of men hauled them onto canoes for transport to Kawaiaha‘o. It took great energy and over five years to build. King Kamehameha III commissioned the building with the support of Regent Kina‘u, Gov. Kekuanao‘a and other ali‘i. In 1839, the cornerstone was laid — rock from the Waianae estate of High Chief Abner Pākī.

Rev. Bingham never saw the church completed. The ABCFM reassigned him to New England in 1840 because the board thought that he had become too involved with political aspects of the Hawaiian Kingdom. The success of the mission and the rising costs of supporting over 200 missionaries in the Pacific led the board to limit support. Pastors were taking side jobs to support their families. By 1863, support ended and missionaries had to either find full employment in Hawai‘i or return to America. Many chose to stay.

Ka Haku Nō Ku‘u Pu‘uhonua

Ka Haku Nō Ku‘u Pu‘uhonua

(A Shelter in the Time of Storm)

Christian churches have always been places of refuge since the apostles formed the first seven churches. Pre-contact Hawaiians set aside certain lands as sanctuaries for the oppressed and understood this concept very well. During the reign of Kauikeaouli Kamehameha III, Kawaiaha‘o became a place where kings and commoners gathered in the shelter of their God and fellowship of other Christians. This tradition continues today.

“‘Ōlelo Hawai‘i was the language of Kawaiaha‘o and it is still a significant part of worship. We have scripture readings in ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i, manaleao and fluent speaker communities in both languages, sermonettes in ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i, and two Sundays a month, “Ka Halawai” all-Hawaiian services,” says member Malia Ka‘ai-Barrett.

In 1843, when Kauikeaouli moved the royal seat of government to Honolulu. Kawaiaha‘o Church became the site of many milestone events of the Hawaiian Kingdom constitutional monarchy. In February 1843, when Lord Paulet and his men took control of the Hawaiian Islands for Britain under threat of force, Finance Secretary Dr. Geritt Judd secretly scribed the king’s letter of protest to Queen Victoria. Hiding in Queen Ka‘ahumanu’s crypt in the graveyard and writing by the light of a single candle, he asked Britain to return sovereignty to the Kingdom of Hawai‘i.

Seven months later, when sovereignty was restored by Admiral Thomas, it was from the steps of Kawaiaha‘o Church that King Kauikeaouli addressed the nation and spoke these famous words: “Ua ma au ke ‘ea o ka ‘āina i ka pono! The life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness!” In 1959, his words became our state motto.

Please note: The Kawaiaha‘o Church community is suspending services and gatherings, and the Bicentennial Celebration during the pandemic. Visit www.kawaiahao.org for future schedules and advisories.

Leave a Reply