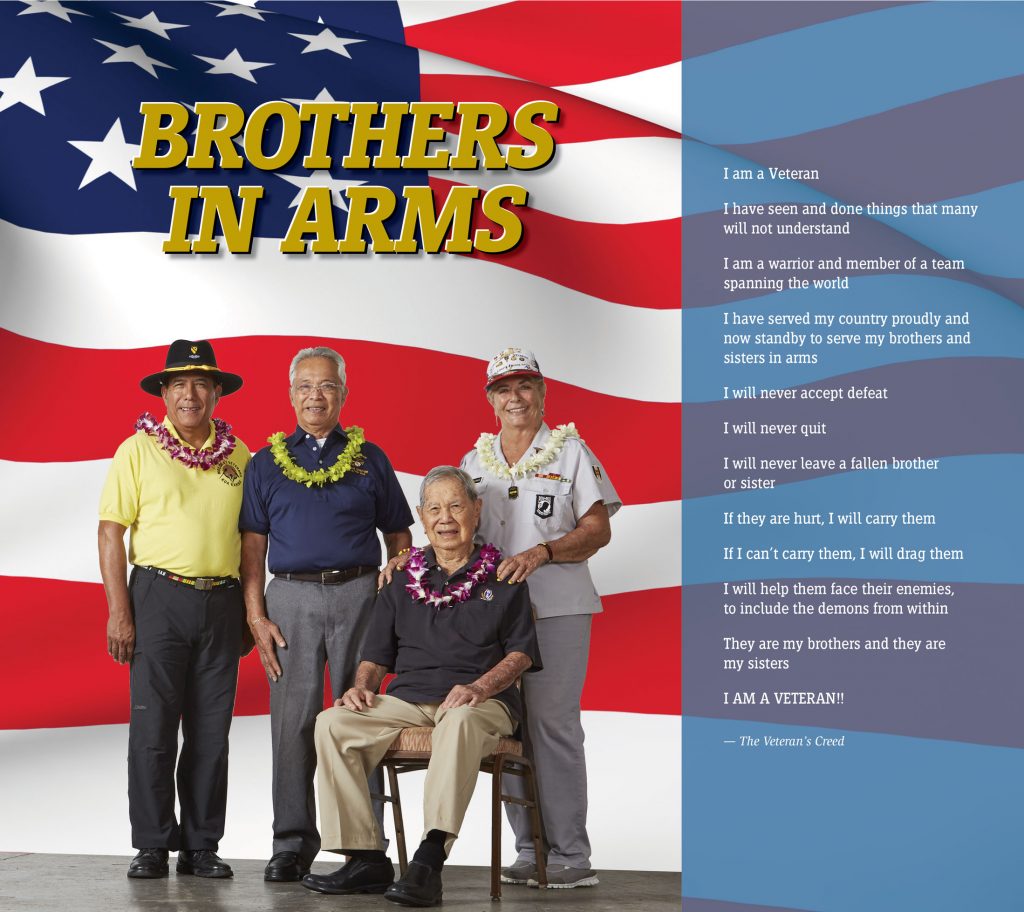

The story of every veteran describes his or her contribution to the defense of American ideals — life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. Their stories always represent their brothers in arms who did not return, reminding us of the terrible price of war in lost lives, destruction of civilian communities, and terrors that infest both mind and soul. We cannot know the profound trauma that military and civilian survivors of war carry in their hearts, but if we listen to what they share, we can be supportive friends, laughing with them when they laugh; crying when they cry.

Over 50,000 senior veterans of World War II, Korea and Vietnam live in Hawai‘i. Add to that another 70,000 younger veterans who either served in peacetime or completed tours in recent wars in the Middle East. Coming soon are Veterans Day on Nov. 11, the 75th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7 and the 50th anniversary of the commemoration of the Vietnam War in May 2017. If you don’t know much about the wars our senior veterans fought, learning a little bit about them will be an eye-opener. Hawai‘i veterans have done so much for our country.

The job of every veteran is a small tactical piece of a massive strategic war operation. Herein lies the dilemma of combat survivors: They don’t call themselves heroes. They call their fallen brothers in arms “real heroes.” In military operations, everyone who follows orders — supply personnel, radio operators, air controllers, pilots, cooks, nurses, mechanics, interpreters, drivers, tankers, military brass and combat soldiers — earns respect.

Civilians assess wars by outcomes — leading to a very different definition of a hero. Just like a naïve child, we ask, “What did you do in the war?”— hoping to hear a battle story. Turn the page and learn what three American brothers and one sister in arms share about their service in three different wars. Their message to us is consistent: All veterans deserve our gratitude and respect.

Ron Gella grew up in Waipahu, where his dad worked for O‘ahu Sugar Company. “I attended the sugar company elementary school, and right after graduating from Waipahu High School, joined the U.S. Marine Corps. First, I was sent to Camp Pendleton in San Diego , California, then to a reserve unit at Pearl Harbor. I was then sent to the main headquarters for 30 days of combat training, and finally, to the attack transport ship, USS Thomas Jefferson for 14 days more training at Yokosuka Naval Base in Japan.”

The Chinese Communist Forces (CCF) had issued an ultimatum to United Nations Supreme Cmdr. Douglas MacArthur that any movement north of the 38th parallel would be met with force. He did not take the threat seriously and on Sept. 15, 1950, the 1st Division Marines were part of a surprise amphibious landing of U.N. forces at the western port of Incheon, just 25 miles west of Seoul. Gen. MacArthur planned the invasion because U.N. allied troops were locked in by communist forces in the eastern Pusan Perimeter. A ruse made the communists believe an attack would come 105 miles south at Kunsan, so only a few enemy units showed up to defend the muddy flats of Incheon. U.N. forces immediately crossed the 38th parallel and headed north to take back the western half of Korea from the communists. Gella’s company landed last, on Sept. 16, and began a bloody fight inland to take Seoul. Gen. Edward Almond declared the city liberated on Sept. 25.

The Chinese Communist Forces (CCF) had issued an ultimatum to United Nations Supreme Cmdr. Douglas MacArthur that any movement north of the 38th parallel would be met with force. He did not take the threat seriously and on Sept. 15, 1950, the 1st Division Marines were part of a surprise amphibious landing of U.N. forces at the western port of Incheon, just 25 miles west of Seoul. Gen. MacArthur planned the invasion because U.N. allied troops were locked in by communist forces in the eastern Pusan Perimeter. A ruse made the communists believe an attack would come 105 miles south at Kunsan, so only a few enemy units showed up to defend the muddy flats of Incheon. U.N. forces immediately crossed the 38th parallel and headed north to take back the western half of Korea from the communists. Gella’s company landed last, on Sept. 16, and began a bloody fight inland to take Seoul. Gen. Edward Almond declared the city liberated on Sept. 25.

Like many combat veterans, Ron does not talk about the details of his combat service. “I prefer to keep it to myself,” he said. “It ended up all right; for that I am grateful.”

Like many combat veterans, Ron does not talk about the details of his combat service. “I prefer to keep it to myself,” he said. “It ended up all right; for that I am grateful.”

“Our mission was to take back the capital of Seoul,” said Ron. “We secured the city, but there was more work to do. After that, we fought at Pusan, and in late November, ships took us up to Wonsan on the east coast, to support the final offensive to take all of Korea from the communists.”

The U.N. campaign up the western part of Korea was successful and troops were approaching the Yalu River on the Manchurian border. Newspapers at home reported that all that remained was to “clean up and get home by Christmas.” All that was left was the northeast corner of Korea, a mountainous region that included Chosin Reservoir. From the port of Hungnam on the east coast of Korea, a force of about 15,000 1st Division Marines, two battalions of the 7th Army and a unit of British Royal Marine Commandos began a 78-mile march on a dirt road through a pass in the Taebaek Mountains to the reservoir. There they would meet U.N. forces coming from the reservoir’s west end. This operation would complete the U.N. mission to liberate the Republic of Korea.

Fighting through roadblocks on the narrow trail through the mountains was successful, and camps were established at Koto-ri, the halfway point, and Yudan-ri, near the reservoir. On the night of of Nov. 27 at Yudan-ri, 120,000 CCF who had secretly taken up positions in the mountains, ambushed the Marines in the valley. Losses were great. On the west end of the reservoir, Commu-nist forces also routed the 8th Army and U.N. troops, who were subsequently ordered to retreat below the 38th parallel.

Ron and the other surviving Marines were ordered to withdraw back down the narrow trail to Hungnam. Besides their disadvantaged position in the tight valley, Marines struggled in clothing and gear that was not sufficient for 30-degree-below-zero temperatures. Casualties were so great that there was no room in hospital tents; blood plasma froze and medications in syringes had to be warmed in the medic’s mouth in order to stay liquid. Many soldiers suffered severe frostbite injuries. At one point on the trail, U.S. Army Engineers built a temporary bridge between two peaks, and after the entire force crossed, blew it up — a bold move that provided a jump on the pursuing CCF. Under the most adverse weather conditions, U.S. fliers helped by suppying some air cover.

Ron and the other surviving Marines were ordered to withdraw back down the narrow trail to Hungnam. Besides their disadvantaged position in the tight valley, Marines struggled in clothing and gear that was not sufficient for 30-degree-below-zero temperatures. Casualties were so great that there was no room in hospital tents; blood plasma froze and medications in syringes had to be warmed in the medic’s mouth in order to stay liquid. Many soldiers suffered severe frostbite injuries. At one point on the trail, U.S. Army Engineers built a temporary bridge between two peaks, and after the entire force crossed, blew it up — a bold move that provided a jump on the pursuing CCF. Under the most adverse weather conditions, U.S. fliers helped by suppying some air cover.

Click by click, the battered U.S. troops pulled together every ounce of reserve and miraculously fought their way back to Hungnam harbor. They sustained more casualties than any other Marine battle but Iwo Jima, and transported out all their dead and wounded with them.

Click by click, the battered U.S. troops pulled together every ounce of reserve and miraculously fought their way back to Hungnam harbor. They sustained more casualties than any other Marine battle but Iwo Jima, and transported out all their dead and wounded with them.

“We brought out over 100,000 Korean civilians, too,” said Ron.

With 3,000 killed in action and 12,000 casualties, including 6,000 wounded in action, the survivors of the Battle of Chosin Reservoir are called “The Chosin Few.” The CCF reported 45,000 casualties. The fighting in Korea continued until the 1953 armistice.

“We boarded ships in Hungnam with thousands of civilian refugees and bugged out to Japan,” said Ron. “From there, I came home to Waipahu.”

Coming home for veterans of the Korean War was difficult. After enduring so much, there was no heroes’ welcome. The military operation is often referred to as “The Forgotten War.”

“When we came home, except for my parents, there was nobody at the airport to meet us — no flag waving, no band, no honor guard — that hollow surprise is something that always stuck with me,” said Ron. “I went home to Waipahu for a while, and then, because I was still in the reserves, they sent me to San Diego. You know what duty they gave me? Gate guard! I will never understand that.”

If you know a veteran who served in Korea, make a special effort to let him or her know they are not forgotten. We may never know how much suffering they endured. Ron and many combat heroes like him don’t seek attention and may never talk about their war stories, except perhaps with other combat veterans who understand how it was there.

We civilians cannot begin to understand what our veterans went through. All we can do is show our gratitude and perhaps make up for the heroes’ welcome they never got. Most of all, personally honor them and their willingness to serve.

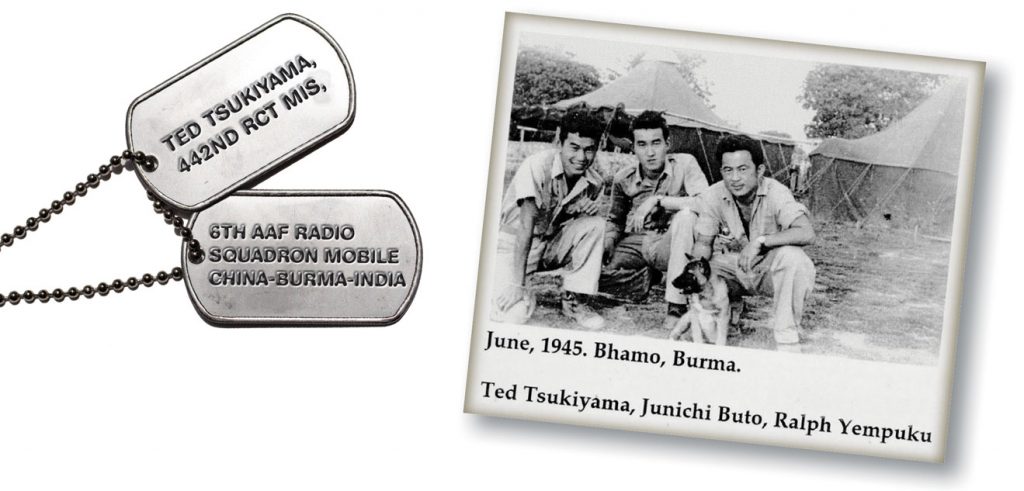

Not all of the 14,000 Nisei of the 100th Infantry Battalion and 442nd Regimental Combat Team (RCT) served in Italy and France during WWII. Over 6,000 were in Military Intelligence Service in many theaters.

Not all of the 14,000 Nisei of the 100th Infantry Battalion and 442nd Regimental Combat Team (RCT) served in Italy and France during WWII. Over 6,000 were in Military Intelligence Service in many theaters.

At 95, Ted Tsukiyama clearly remembers the Pearl Harbor attack in 1941. An ROTC student at University of Hawai‘i, he was told to report for military duty in the Hawaii Territorial Guard (HTG) to protect bridges, reservoirs, pumping stations, schools. Soon after that, Washington ordered Japanese-Americans dismissed from HTG, classifying Ted as a “4C Enemy Alien.” Japanese-American active military at Schofield Barracks were also reassigned to nonmilitary posts.

“Living in Hawai‘i, our Japanese ancestry never mattered,” said Ted. “But after Pearl Harbor, Japan was our enemy and our enemy had faces just like ours. One time, a Hawaiian guy asked a Japanese American HTG member, ‘Who you gonna shoot?’ The distrust hurt; I was an American.”

In California, first-generation Japanese immigrants were uprooted and moved to internment camps in the interior of the mainland, but for the moment, American-born Nisei, who the military called “Americans of Japanese Ancestry” (AJA), were neither friend nor foe.

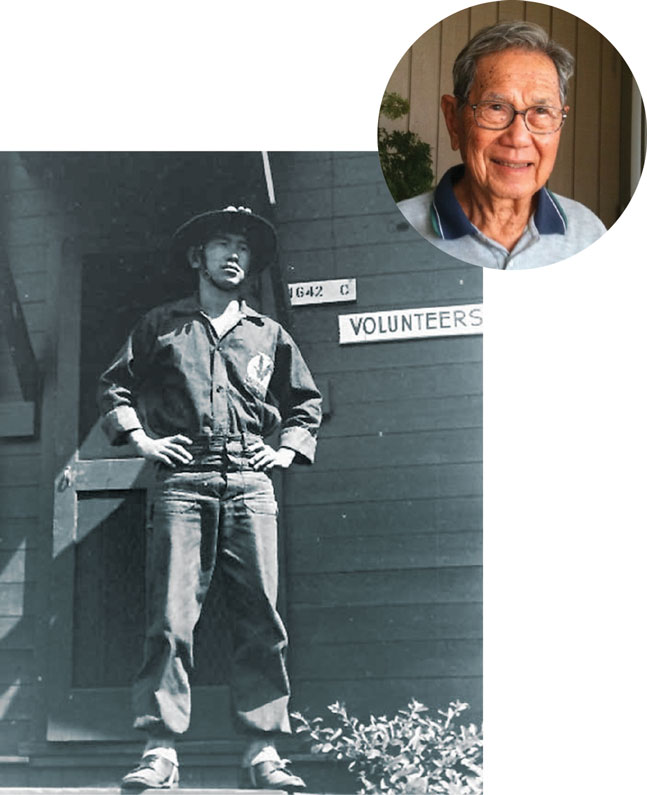

In 1942, Japanese-American ROTC students at University of Hawai‘i boldly declared their loyalty to the “Stars and Stripes” and petitioned UH to form the Varsity Victory Volunteers (VVV). Once assembled, this labor battalion assisted the 34th Army Engineers to construct military installations and fences. They also installed barbed wire defenses and worked in quarries.

In 1942, Japanese-American ROTC students at University of Hawai‘i boldly declared their loyalty to the “Stars and Stripes” and petitioned UH to form the Varsity Victory Volunteers (VVV). Once assembled, this labor battalion assisted the 34th Army Engineers to construct military installations and fences. They also installed barbed wire defenses and worked in quarries.

“I was a VVV, and as soon as the War Department formed a special Nisei combat unit in 1943, I signed up,” said Ted. The Nisei excelled in military training, and soon, the 100th Infantry Battalion, 442nd RCT, 552nd Field Artillery Battalion and 1399th Engineering Construction Battalion were sent to fight in Italy and France. This band of brothers with the “Go for Broke” motto became World War II’s, most decorated combat unit, earning nearly 16,000 decorations, including 21 Congressional Medals of Honor and eight Presidential Unit Commendations.

“In 1944, after completing Army boot camp at Camp Pendleton instead of combat training in Mississippi, I was assigned to Military Intelligence Service Language School (MISLS),” said Ted. “The War Department had concluded that Americans of Japanese ancestry who had attended Japanese language schools in Hawai‘i or Japan would be very useful in intelligence.”

The first MISLS was at the Presidio, but in 1941, anti-Japanese sentiment was so rife

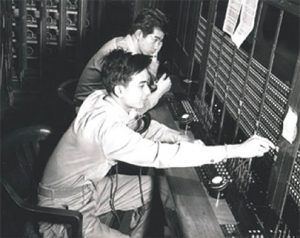

in California that the War Department moved the school to Fort Snelling, near St. Paul and Minneapolis, Minnesota, where the students would be safer. From 1942 to 1945, over 6,000 students — mostly Nisei — trained as translators, interpreters and code crackers to assist allied troops in the Pacific theater. “I spoke Japanese but had to learn heigo military language for my job, intercepting and translating into English all the Japanese Air Force pilots’ radio communications in the China-Burma-India air space.”

The first MISLS was at the Presidio, but in 1941, anti-Japanese sentiment was so rife

in California that the War Department moved the school to Fort Snelling, near St. Paul and Minneapolis, Minnesota, where the students would be safer. From 1942 to 1945, over 6,000 students — mostly Nisei — trained as translators, interpreters and code crackers to assist allied troops in the Pacific theater. “I spoke Japanese but had to learn heigo military language for my job, intercepting and translating into English all the Japanese Air Force pilots’ radio communications in the China-Burma-India air space.”

Ted’s parents had come to O‘ahu from Tokyo in 1911 and worked in a relative’s retail store — the Japanese Bazaar. He grew up American in a large Nisei community. “We knew about the Japanese wars with China but never thought about an attack on Hawai‘i,” said Ted.

“I was assigned to the 6th Army Air  Force Radio Squadron Mobile Unit in the China-Burma-India Theater,” said Ted. “We were a ‘Special Interception Unit,’ supporting the 10th Air Force and the British forces who were taking back Burma [now Myanmar]. We were eavesdroppers. The Japanese occupied nearly all of Southeast Asia and there was a lot of chatter on the airwaves. They had no idea we were listening. My job was to transcribe, translate and report all communications, and report them to U.S. Intelligence HQ. We had 150 Nisei from the 442nd intercepting, translating, interrogating prisoners and even broadcasting messages into enemy territories. We had to be careful not to be mistaken for the enemy; buddying up with a haole soldier was a wise move.”

Force Radio Squadron Mobile Unit in the China-Burma-India Theater,” said Ted. “We were a ‘Special Interception Unit,’ supporting the 10th Air Force and the British forces who were taking back Burma [now Myanmar]. We were eavesdroppers. The Japanese occupied nearly all of Southeast Asia and there was a lot of chatter on the airwaves. They had no idea we were listening. My job was to transcribe, translate and report all communications, and report them to U.S. Intelligence HQ. We had 150 Nisei from the 442nd intercepting, translating, interrogating prisoners and even broadcasting messages into enemy territories. We had to be careful not to be mistaken for the enemy; buddying up with a haole soldier was a wise move.”

The Imperial Army’s plan was to starve out the Chinese by closing down the supply route from India. While the 13th Air Force was helping the Chinese allies, the strategic mission of the 10th Air Force in Burma, which Ted’s unit supported, was to protect truck convoys and chase off the Imperial Army. “We worked in four teams around the clock and moved around wherever we were needed, keeping track of what the Japanese pilots were up to — sometimes in Ledo, India, near the Burma border, or on the China end of the road at Bhamo and Myitkyina. We took our radio equipment wherever we were needed — our intelligence helped the British recover Burma and kept the Chinese allies alive.

“After the war, I finished college on the G.I. Bill at Indiana University. In 1950, I graduated from Yale Law School, returned home to Honolulu and began a long career in general law and labor-management arbitration. My wife, Fuku, and I raised one daughter and two sons.”

Hongwanji Mission in Honolulu has named Ted a “Living Legacy of Hawai‘i.

Ted served decades as a historian for the 442nd RCT Veterans Club and MIS Veterans Club in Honolulu. His detailed and thoroughly indexed research, titled, “The Ted Tsukiyama Papers,” is a compilation of public records, correspondence and veteran interviews. It is available to the public at University of Hawai‘i Hamilton Library and Evols open-access digital library. To read the papers and learn more about the Nisei in WWII, visit www.evols.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/.

O.K. Now I’m sure you wonder how a nice, young Jewish girl from Los Angeles, who hung out in Beverly Hills, ever got to Vietnam. Before I start my story, I want to thank all of the medics, corpsmen and dust-off crews that were over there; without them, we couldn’t have done it.

Well, as a little kid (never ask a lady her age, right?) after WWII, I saw a war movie called, So Proudly We Hail with Jeannie Crane, Veronica Lake (the sexy blond with hair hanging over one eye) and Claudette Colbert. Three Army nurses in Bataan heard the enemy coming toward their hospital tents, but they couldn’t leave their patients (it was considered desertion) — so Veronica put a grenade in her bosom, went outside and blew up the enemy. I decided then and there I wanted to be an Army nurse in combat.

I always remembered that movie. After high school and college, I went off to nursing school in San Francisco. I was a nurse, but there wasn’t a war then, so I returned to LA and became an operating room nurse — they need those in a war.

When the U.S. got involved in Vietnam, I was still very impressionable and saw the movie In Harm’s Way. I thought, OK. Here’s my chance. I had a long talk with my mother because I was an only child; my father passed away when I was a kid. She could have prevented me from putting myself in harm’s way.

I also researched the military branches. I didn’t want the Navy, since I got queasy even on the moored Queen Mary in Long Beach — so I walked into the recruiting office in LA and told the recruiter that I was a nurse, and I wanted to join the Army and go to Vietnam. Needless to say, he thought I was crazy.

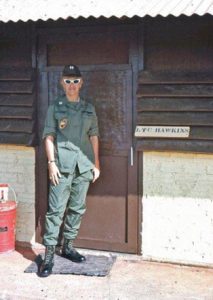

Right before I was sworn in with a bunch of other people, I got cold feet and almost backed out, but the recruiter had a good hold on me. By that afternoon, I was Capt. Rona Adams, U.S. Army Nurse Corps. I had signed my life away for two years.

A few months down the road, I reported for about seven-and-a-half weeks of basic training at Ft. Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas. If you ever saw Private Benjamin, that was me.

Shipping out, I sat in a bar at the San Francisco Airport overlooking the UC Berkley campus wondering what the heck did I do? I may never come back, for heaven’s sake. I may never be in the Polo Lounge at the Beverly Hills Hotel again! I’m going to be taking a bath out of a helmet…

Packed in my footlocker were all the wrong uniforms for Vietnam, a jungle combat zone with two types of weather — hot and wet or hot and dry. They gave us standard fatigues and boots, men’s long johns and headgear with warm earmuffs — leftovers from Korea. It also contained 200 pounds of Kotex! They didn’t have that stuff over there. Things have really changed for women in the military.

Over the Pacific, I downed a few toddies, stopped in Guam and then arrived in Vietnam. Those puffs of smoke in the sky sure as heck didn’t look like clouds… and camouflaged stuff with sandbags all over the place. Then it struck me. Oh my God, I am in a war!

At Saigon’s airport, I sat on my footlocker and waited. An older Navy officer came by, looked at my nametag and asked, “Is anyone coming to pick you up, Capt. Adams?” “I don’t think so, sir,” I replied. “Do you know where you are headed?”

At Saigon’s airport, I sat on my footlocker and waited. An older Navy officer came by, looked at my nametag and asked, “Is anyone coming to pick you up, Capt. Adams?” “I don’t think so, sir,” I replied. “Do you know where you are headed?”

“I don’t think so, sir,” I said, handing him my orders, (which I did not know how to read). He told me to sit tight and got a couple of guys to pick me up and take me to see the chief nurse. I guess my orders were for Tay Ninh, but the chief nurse reassigned this operating room nurse (who also ran a cardiac catheter lab) to the 3rd Field Hospital in Saigon. Then the guys took me to BOQ #2 for the night.

That next day, the chief nurse showed me around the hospital. I had seen people die, but I was not prepared for the horrific injuries I saw that day. I met a soldier with a suction chest wound, who could hardly get enough air to speak. When I asked him how he was, he sputtered, “Fine.” That got me, and I will say that I cried my way through Vietnam. American soldiers press through unbelievable injuries and never complain. They use humor to cope with the most devastating situations. Their valor impresses me so much.

Our hospital was right in the city of Saigon. Military Police were our first line of defense, and fortunately, we never came under attack. During the Tet Offensive, we had 200 casualties arrive in the first 10 to 12 hours. I was the head nurse of the emergency room, and I don’t know how we got through it.

Our hospital was right in the city of Saigon. Military Police were our first line of defense, and fortunately, we never came under attack. During the Tet Offensive, we had 200 casualties arrive in the first 10 to 12 hours. I was the head nurse of the emergency room, and I don’t know how we got through it.

After Tet, I extended. Being a beach bum from California, I chose the 8th Field Hospital in NHA Trang as my duty station, because it was near the ocean. Actually, this was a more dangerous location because we were right next to an airfield connected to the 5th Special Forces camp — both juicy targets. Special Forces posted a list of their KIAs. After Tet Offensive, it got very long. It was hard to lose those guys.

I left the Army after two tours and returned home, but nobody asked me about my war experience. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was not even a recognized diagnosis then. Even if it was, doctors or nurses with a mental disorder could never find work. I didn’t know any other veterans, so I never talked about Vietnam.

I left the Army after two tours and returned home, but nobody asked me about my war experience. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was not even a recognized diagnosis then. Even if it was, doctors or nurses with a mental disorder could never find work. I didn’t know any other veterans, so I never talked about Vietnam.

I gravitated away from operating room work, became a director of nursing and then took a corporate job managing surgical services for seven hospitals. Later, I moved to Hawai‘i and managed a surgicenter in Honolulu.

After two years, I retired and got involved in service to other veterans. I call it “paying back.” Veteran volunteers find it a very healthy way to connect with our memories and help others do the same. A lot of our brothers in arms are hurting like we are.

I belong to Jewish War Veterans out of respect for my father, the Veterans of Foreign Wars, and I am also the president of O‘ahu Chapter 858 of the Vietnam Veterans of America (VVA), the only chapter in Hawai‘i.

I belong to Jewish War Veterans out of respect for my father, the Veterans of Foreign Wars, and I am also the president of O‘ahu Chapter 858 of the Vietnam Veterans of America (VVA), the only chapter in Hawai‘i.

When I take my two certified therapy dogs, Bindi and Mele, to Tripler Army Medical Center to visit the patients, I wear my special VVA polo shirt that says, “I’m a Vietnam Vet, and “I am Bindi and Mele’s Mom.” The nurses thank me for my service and say that we oldtimers paved the way for them. That feels good. Friends who understand your burdens are the best kind of support. Together, we can do anything!

Bo (Cummins) Mahoe calls himself a reluctant soldier. Draftees were given 30 days to take an aptitude test and talk with recruiters about duty options, but Bo and his cousin didn’t bother. They went straight into the infantry. “I fit the Army’s requirements for pointman, the person who walks through the jungle 30 to 40 feet ahead of the squad, watching out for booby traps and signs of enemy combatants. It’s the ‘point of the spear’ concept,” he said. At 20, he was in front of the front line.

“Philip Chun, my cousin from Honokohau, Maui, and I got drafted together, and we spent our military service side by side. We were determined to return to Lahaina when our duty was over.” Their will to live and return is the core of American grit and a shining ideal. But for those who make it, survivor’s guilt is a dark reality.

“Our training in California was almost six months long; we landed in Vietnam Feb. 1,” said Bo. “For us island soldiers, it was pretty cold.” In Vietnam, Bo and his brothers in arms faced a war very different war from WWII. The former French-Indonesian Republic of Vietnam had been fighting against the Viet Cong communists in the north for two decades. Civilians in North and South Vietnam survived by complying with both sides, creating a complicated web of stealth, intrigue and deception that often seemed impenetrable. Taking ground was a measure of victory in previous wars, but not in Vietnam. Sometimes the troops wondered why they fought for ground only to give it up the next day.

“Our training in California was almost six months long; we landed in Vietnam Feb. 1,” said Bo. “For us island soldiers, it was pretty cold.” In Vietnam, Bo and his brothers in arms faced a war very different war from WWII. The former French-Indonesian Republic of Vietnam had been fighting against the Viet Cong communists in the north for two decades. Civilians in North and South Vietnam survived by complying with both sides, creating a complicated web of stealth, intrigue and deception that often seemed impenetrable. Taking ground was a measure of victory in previous wars, but not in Vietnam. Sometimes the troops wondered why they fought for ground only to give it up the next day.

Bo, a descendant of High Chief Pi‘ilani, grew up in a Lahaina home fronting Mālā Wharf. Like all American kids, he was hooked on Hopalong Cassidy, Rowdy Yates, John Wayne, Randolph Scott and The Lone Ranger. He and a large pack of neighborhood kids enjoyed playing outdoors and slinging cap gun six-shooters.

“Growing up in the diversity of Hawai‘i made adjusting to the military much easier to handle,” said Bo. “The Vietnam jungle, although more humid than home, offered the same terrain, vegetation and a familiar botanical garden most island kids grew up in. We were the only ones who recognized the edible plants.”

“Growing up in the diversity of Hawai‘i made adjusting to the military much easier to handle,” said Bo. “The Vietnam jungle, although more humid than home, offered the same terrain, vegetation and a familiar botanical garden most island kids grew up in. We were the only ones who recognized the edible plants.”

Bo credits his Army training, too. “The Army helped us stay alive,” Bo said. “They teach that everyone — and especially those involved in combat arms (point of the spear) — should always be prepared. Preparation, like school homework, offers the best outcome for any obstacle. Another military mantra is ‘adapt and overcome.’ If a fellow soldier is wounded or killed, you have to be able to continue the mission, even without the support of that individual.”

When American troops first deployed to Vietnam, pointmen drew first fire. As the war went on, the Viet Cong learned that they could save ammunition and kill more Americans by letting the pointman go by and waiting to ambush the full platoon. “Why kill these guys — let them go and shoot the bunch behind. By the time I got there, the longevity of a pointman was pretty good,” said Bo. “I stayed alive 10 months.”

“Another problem for us island guys was when our squad was being picked up by choppers in the jungle,” said Bo. “As pointmen, Philip and I would run out to be extracted first. Sometimes the helicopter gunners would fire at us because Chinese-Hawaiian guys look like Viet Congs. That was hazardous duty! “

Like many veterans, Bo Mahoe does not talk about the terrors and brutality he faced. But he is deeply involved with service to other veterans, for whom he serves as an advocate.

“The army offered us a very abrupt transition from combat duty to civilian life,” Bo said. “In 48 hours, cousin Phillip and I went from sergeants to misters. Today, soldiers coming back from Iraq have six months of service in the U.S. with transition programs to help them re-enter civilian culture. When I came home to Maui, there was nobody to talk to. A veteran on O‘ahu can interact with active military and their families because the Army, Navy, Marine, Air Force and Coast Guard all have strong representation on O‘ahu. I have only one high school classmate who experienced combat, Peter Nararino. We came home different. Besides this social isolation at home, Veterans Affairs was sluggish in its efforts to help the Vietnam veteran. They did not recognize PTSD until 1981. Since the ’90s, the VA has made major strides toward providing benefits and services to veterans from all wars.”

Veterans can relate to other veterans in service organizations. Bo is member of Koa Kahiko — Molokai Veterans Caring for Veterans. “Two days before Larry Helm, commander and one of the founders, died, he said to me, ‘Take care of the veterans!’ So I work with many veterans groups and events on Maui. I am a member of the Maui Nō Ka ‘Oi Chapter 282, Korean War Veterans, and it reaffirms that although the theaters are different and the weaponry is different, the human experience of combat is identical.

Even our Global War on Terrorism soldiers work in different climates, with more sophisticated weaponry, but the common denominator is the combat experience.

“Only half of 1 percent of Americans wears the uniform,” Bo said. “Female veterans have shared unique perspectives of what was formerly a male-dominant culture. Again, I was a reluctant soldier; reluctant in that I was drafted into the military. Since the draft ended in the mid-1970s, individuals serving in today’s military do not have the reluctance I had. I salute their patriotism.”

When asked what wisdom he has for friends and family of veterans, Bo shared this advice: “Although our nation honors our veterans on Veterans Day, Nov. 11, all citizens should extend that honor to them every day. Veterans have ensured that American citizens enjoy freedoms and liberties, daily, so, gratitude one day a year is insufficient. Remember that the young veteran man or woman left home a civilian and returned home a changed individual. Honor that change.”

These four heroes teach us this: It is the duty of civilians to welcome home veterans. When they reach out, we may be able to help them reconnect, find medical and social assistance, find meaningful work and create a living space that is safe and comfortable. We can never understand what they endured, how haunted they are by memories or how difficult it is to re-enter civilian life. However, we can give them the respect and honor due a warrior and protector of freedom.

Leave a Reply