Anona and Joseph “Nappy” Napoleon love the sea. Their kuleana is to respect and care for the sea by practicing and perpetuating cultural traditions of their ancestors who lived on and near the ocean. We call them “watermen.” Kō ā moana may be men or women, surfers, fishermen, paddlers, sailors or divers. They know the power and majesty of the sea in every season and type of weather. They trust their ancestral skills and honed talents, and mentor the next generation to carry them on. It’s clear that that they are more comfortable and happier on the water than on land. With kō ā moana at the helm, dark swells become waterslides, rough seas promise exciting adventures and being alone on the open ocean brings calm and freedom.

Anona and Joseph “Nappy” Napoleon love the sea. Their kuleana is to respect and care for the sea by practicing and perpetuating cultural traditions of their ancestors who lived on and near the ocean. We call them “watermen.” Kō ā moana may be men or women, surfers, fishermen, paddlers, sailors or divers. They know the power and majesty of the sea in every season and type of weather. They trust their ancestral skills and honed talents, and mentor the next generation to carry them on. It’s clear that that they are more comfortable and happier on the water than on land. With kō ā moana at the helm, dark swells become waterslides, rough seas promise exciting adventures and being alone on the open ocean brings calm and freedom.

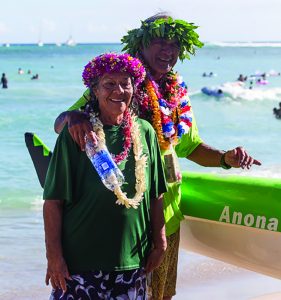

“The ocean brought us together,” says Anona as she smiles at Nappy. “And it keeps us together, too.” For the last 55 years, the Napoleons raised five sons by the sea and taught many mo‘opuna the ways of the sea. Their love affair with each other and the ocean honors the family traditions of the Nāone ‘ohana of O‘ahu, and the Napoleon ‘ohana of Kaua‘i, Hawai‘i Island and O‘ahu. Their steadfastness ushers in new generations of kō ā moana, people of the ocean.

The Man Behind the Woman

Joseph “Nappy” Napoleon, Champion Paddler and Steersman. Hawaiian Waterman Hall of Fame Inductee, 2010.

On Sunday, Oct. 13, Uncle “Nappy” Napoleon, Hawai‘i’s revered champion paddler, will don a green shirt to compete in his 62nd world paddling championship — the Moloka‘i Hoe. This race across the Ka‘iwi Channel starts at Hale o Lono Harbor on Moloka‘i’s west shore. After some five hours and 41 miles of paddling across the shallow Penguin Banks and then braving the “washing machine” of the deep churning Ka‘iwi Channel, paddlers make land at Duke Kahanamoku Beach in Waikīkī. Of the seven most dangerous channels in the world, Ka‘iwi outranks the English Channel for rough seas.

Nappy first paddled across this channel in 1957, and in 1958, he won the inaugural Moloka‘i Hoe official competition. Among his five additional wins was the 1966 event, when 40-knot winds and 20-foot swells in the channel savaged the race. Only six of 12 canoes finished. One crew lost their canoe. Nappy’s team prevailed, despite capsizing three times and losing the outrigger. Beating out all the international competition for wins in ’61, ’69, ’72 and ’73 was much easier than in ’66.

Although Nappy is a renowned expert steersman, he is a competitive paddler first — often helping his team paddle hard to make landfall.

“In the early days, I used to steer the canoe on a high line and surf down to Waikīkī. But nowadays, I pick lines depending on conditions,” says Nappy.

In 2001 and again in 2003, his “60s” team won their division. In the sixth seat, he is moving all the time — adjusting the trajectory of his canoe with every push of the currents, helping paddle up a bump or cutting a diagonal to the next swell. He is the king of riding swells — what the Napoleon ‘ohana calls “connecting the bumps.” This skill builds on a deep knowledge of the sea under all conditions and a “feel” for how the canoe responds to the most delicate tension on the steering paddle. Sometimes Nappy zigzags between swells coming from two directions. Other times, he’s surfing downwind. If you watch Nappy’s canoe turn around a regatta pilon, don’t blink — or you’ll miss it. If turning on a dime were easy, all the canoes would do it that way.

“Way back, Ben Finney came to me and asked me to help him figure out a paddling strategy for pulling Hōkūle‘a through the doldrums,” says Nappy. (The doldrums is a band of flat ocean near the equator where winds cease. Sailboats can get becalmed for days and weeks.)

Nappy was not convinced that paddling a huge sailboat would work. Eventually, Hōkūle‘a carried a portable outboard motor with a long shaft to drive through the calms.

“I met Mau Pialug when he came here from Micronesia, but I decided not to go to Tahiti with Hōkūle‘a anyway because Herb Kane wanted full-blooded Hawaiian crew members. I stuck to paddling and racing.”

Two years ago was the first time Nappy Napoleon was racing Moloka‘i Hoe without his wife at his side. Team Napoleon’s channel beacon and anchor was at home, recovering from a stroke. Now Nappy’s life is much more than racing or coaching at Ānuenue Canoe Club. He is part of a family caregiving team supporting the love of his life.

The Woman Behind the Man

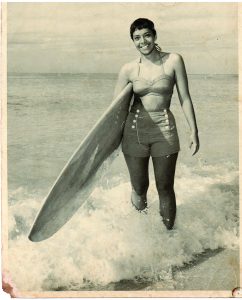

Anona Nāone Napoleon, PhD, Mākaha Surf Queen, Champion Paddler, Surfing Coach. Hawaiian Waterman Hall of Fame Inductee, 2014

Anona Nāone came from a Kaimukī surfing and kayaking family and was one of the only girls surfing big waves at Waimea Bay in the late ’50s. She taught surfing and was sponsored to try out for the 1960 and 1964 Olympic kayaking teams. Tragedy struck in 1960, when she suffered a severe diving accident that left her temporarily paralyzed for nearly a year. Nevertheless, she recovered fully to compete in and win the 1961 International Mākaha Surfing Contest, claiming the coveted Mākaha Surf Queen title.

Anona was not only beautiful but also a brilliant student at Star of the Sea Catholic School. She went on to the University of Hawai‘i and returned to teach at Star of the Sea — the place that inspired her to follow a vocation in education.

A teaching career did not keep this woman of the ocean from pursuing competitive water sports. Anona eagerly joined ‘Onipa‘a, one of two women’s crews to first paddle across the Ka‘iwi Channel. For 20 years, women were not allowed to complete in paddle races across Ka‘iwi. But in 1975, the men of Waikīkī Surf Club agreed to coach a team of seasoned female athletes from Outrigger, Lanikai and Kailua canoe clubs for their first open ocean voyage. The Healani Canoe Club put up a second canoe and both teams completed the crossing.

A teaching career did not keep this woman of the ocean from pursuing competitive water sports. Anona eagerly joined ‘Onipa‘a, one of two women’s crews to first paddle across the Ka‘iwi Channel. For 20 years, women were not allowed to complete in paddle races across Ka‘iwi. But in 1975, the men of Waikīkī Surf Club agreed to coach a team of seasoned female athletes from Outrigger, Lanikai and Kailua canoe clubs for their first open ocean voyage. The Healani Canoe Club put up a second canoe and both teams completed the crossing.

When the first women’s world championship of paddling, Nā Wāhine o Ke Kai, was first held in 1979, Anona’s canoe crossed the Ka‘iwi with the best time. Her crews also won in ’87, ’88 and ’89. In 1998, Anona Napoleon came in first at the International Polynesian Canoe World Sprint Championships in Fiji.

Part of being a woman of the ocean is perpetuating the Hawaiian nohona — the Hawaiian ways of doing things. In 2003, Anona took on a new challenge to apply Hawaiian values and methods to her teaching profession.

Anona went back to college and earned her doctorate in education. Her thesis focused on developing culturally responsive primary education curricula based on the Hawaiian method of conflict resolution — ho‘oponopono. Like the successful culturally focused social and healthcare services explored by Mary Kawena Pūku‘i in the book Nānā I Ke Kumu, Anona’s work created objectives and lesson plans that would engage students using traditional Hawaiian learning styles and mentoring methods.

Waikīkī Beach Boy and the Mākaha Queen

Nappy was born in Kealakekua on Hawai‘i Island, where, as a small boy, he remembers paddling everywhere and racing canoe with his cousin. The family moved to Kapahulu, O‘ahu, and he remembers Waikīkī Beach when he was 10 years old. Nobody under 16 could race, but when the canoes were short a man, Nappy would be allowed to jump in on a training run. He was a natural who pulled hard and never got tired.

“I was lolo, you know. Not so good at schoolwork and only made it through the seventh grade,” Nappy says. “I was a hard worker, though, and a strong paddler — racing canoes with my cousin when I was little. I went to Ala Wai Trade School, paddled with Outrigger Canoe Club and worked at Waikīkī beach giving canoe rides to tourists for 75 cents, and surf lessons for four dollars an hour. Now, the lessons are expensive! I knew all the guys at Beach Boys concession: Sam ‘Steamboat’ Mokuahi, ‘Rabbit’ Kekai, ‘Chick’ Daniels, the Kahanamokus — I carried Duke’s board. After he retired, he came to the beach to talk story and I listened. I remember how much fun it was to cut the waves in ‘Ka Moi,’ his big koa canoe. It weighed more than 600 pounds.

“I had a lot of friends, but I didn’t like parties — didn’t go out much. I was friends with Anona’s brothers, who worked for Aloha Airlines, and went with them to dive Pāpi‘i, Kaunakakai-side, Moloka‘i. They all looked after Anona and I did, too. I was another big brother to her. One day in 1959, I got up the courage to tell her that I didn’t want to be her big brother anymore.”

It worked. Nappy and Anona dated for six years, during which time she trained for the Olympics. Being a Beach Boy didn’t lend itself to raising a family, so Nappy landed a job making cement tiles. “I told ’em I can work hard. Just show me what to do.” Eventually, that job led to a career in construction.

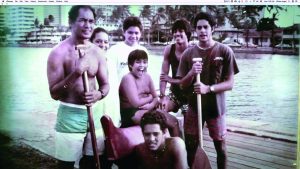

The Sea Brings Us Together

Anona and Nappy wed in 1965. They were a handsome couple, brought together by their love of the sea. “Kō ā Moana,” those of the ocean, raise their kids by the sea, showing them how to respect the power and beauty of the sea in every kind of weather. A year later, Joseph (Joey) was born; two years later, twins Aaron and Darryn. Later on, David and Jonah. The Napoleon family spent every weekend and summer at the beach, morning ’til night. The kamali‘i came to trust their ability to ride the waves, currents and winds. They also learned to mālama the treasures of beach and reef.

Getting to know their island was part of the mentoring. Sometimes Nappy and Anona took the boys out of school so the family could surf a famous spot together. That is how seriously Anona and Nappy felt about passing on the knowledge of their kūpuna — water sports, surfing, paddling, swimming and always having fun as a family.

Today, Napoleon mo‘opuna number 15 and great-grandchildren, 24. Grandson Riggs is a 20-year-old stand-up paddler who remembers being out in Grandpa’s canoe when he was 8 years old, with Nappy behind him, telling what to do. Nappy calls Riggs and his dad, Aaron, “naturals” because they instinctively knew how to do well in races. In 2012, when Riggs was 12, he rode his stand-up paddleboard across the Ka‘iwi solo in seven hours — the record for the youngest person to make that crossing.

“My boys and mo‘opuna are ocean people,” says Nappy. “One time, Anona and I took the boys by Publics reef break near the zoo and waves were pretty good. I went out with them, and when I looked back, those kids were doing 360s and surfing right into the wall! When I came out, Anona said, ‘I thought you were watching the boys?’ I told her, ‘Hey — no need. They know what they’re doing.’”

Preservation is not “knowing about” traditions but practicing them. Nappy and Anona also modeled their devotion to each other, deep respect for one another’s talents and the happiness that comes when a family sticks together. These were lessons well-learned; the boys are raising their own families, and 39 Napoleon mo‘opuna will carry on the legacy to be humble, share aloha and go after your passion. “You know, our boys helped build this house. Nappy taught them construction skills, too, and they could figure out the plan — even when the installers were stumped,” says Anona.

We Love Being Together

Since her stroke in 2018, Anona has been rehabbing at home in Pālolo Valley. Some days are easier than others, but the Napoleon family is also paddling this canoe with her. For 55 years, Nappy has said that he is “a lucky guy” and that he owes all his success to his wife. They love being together, and with Nappy at her side, Anona is safe and confident, surrounded by the love of her family. Anona requires care every day, so Christie (son Aaron’s wife’s friend’s sister) provides home care on weekdays. Nappy covers nights. Every weekend, a homecare agency comes in to help.

This summer, Nappy was able to teach a summer paddling program three mornings a week for 35 ‘Iolani School students at Ānuenue Canoe Club headquarters. After a couple of hours, he’s back with Anona doing chores or enjoying the shade under the mango tree in the yard.

“His mom was disabled,” says Anona. “He cooked and took care of the house for her. And before we got married, he helped me when I was laid up.”

Her sweet, melodic voice doesn’t match her resume — world-class athlete, PhD teacher, mother and grandmother. With the grace and dignity of her ancestors, Anona shares aloha, smiles and lets the love of her life do the talking.

Her sweet, melodic voice doesn’t match her resume — world-class athlete, PhD teacher, mother and grandmother. With the grace and dignity of her ancestors, Anona shares aloha, smiles and lets the love of her life do the talking.

“I hope I did not talk too much about paddling,” says Nappy. “You know I love to paddle, but my life is really about my wife.”

In one of life’s huli, Anona is the center of attention again. Her accomplishments raised the bar for women in water sports, while she was preparing thousands of Star of the Sea students for high schools and college and bringing up five sons.

At her induction into the Hawaiian Waterman Hall of Fame, Anona said, “The reason I stand before you tonight is because of the men in my life, including my husband, Nappy… Thank you for 50 wonderful years.”

From the nurturing of her family to the protection of her brothers and the unconditional support of her husband, the men in her life recognized her talents. With the encouragement of her academic peers and the love, respect and trust of her sons and their families, Anona is still the graceful, humble and smiling beacon. Her family takes this opportunity to fuss over her, paying back and forward the blessing of her deep and unfailing aloha.

The man behind the woman, who has for years said, “All I am comes through my wife,” applies his tireless energy to caring for her now. “It’s not a big deal,” says Nappy. “I love to do it and I have lots of help. We still love being together; we still happy.”

The man behind the woman, who has for years said, “All I am comes through my wife,” applies his tireless energy to caring for her now. “It’s not a big deal,” says Nappy. “I love to do it and I have lots of help. We still love being together; we still happy.”

A Lesson from Paddling

Remarkably, aging in place requires some of the same skills as paddling. Caregiver training is minimal, and you just have to jump in and do it. Every day brings new swells, winds and weather. But you must be very good at keeping a steady pace to make headway. As a caregiver, you must follow the pattern of the swells to your advantage, staying just in front of the wave as long as you can. You learn to use its natural energy and less of yours.

At the end of a good ride down a wave comes a lull, where steady paddling is required to move forward to the next crest. Paddling up takes a bit more energy, but by keeping steady and on course, you will soon be off and gliding easily again.

An important Hawaiian point of view that Anona teaches her mo‘opuna and her students helps us in caregiving, too. It’s this: The ocean between us does not separate us, it connects us to each other. In aging, the time between today and our elder years connects all of us. We are all on the same voyage. The line we follow, the path we choose, may alter how long it takes to get there, or how difficult the going may be. Our skills to navigate rough seas and ride the waves can make the journey easier. As we fly our colors in the regatta of our elder years, it’s not about racing to the finish line — it’s about getting there and enjoying the ride with our family and friends.

An important Hawaiian point of view that Anona teaches her mo‘opuna and her students helps us in caregiving, too. It’s this: The ocean between us does not separate us, it connects us to each other. In aging, the time between today and our elder years connects all of us. We are all on the same voyage. The line we follow, the path we choose, may alter how long it takes to get there, or how difficult the going may be. Our skills to navigate rough seas and ride the waves can make the journey easier. As we fly our colors in the regatta of our elder years, it’s not about racing to the finish line — it’s about getting there and enjoying the ride with our family and friends.

As Anona Napoleon says, “It’s about aloha. Be humble, show your aloha freely to everyone, and above all, have fun.”

Nappy and Anona founded the Ānuenue Canoe Club in 1983 at the Hilton Hawaiian Village lagoon. For 36 years, Anona, Nappy and son Aaron, also an accomplished waterman, have taught thousands of Honolulu and visitor children to paddle, including kids from A¯nuenue Hawaiian Immersion School. Club members trained for races and regattas year round. Nappy is the head coach, and at 78, he competes with a “70s” Ānuenue crew. Join the healthy fun of paddling, visit www.AnuenueCanoeClub.org.

Leave a Reply