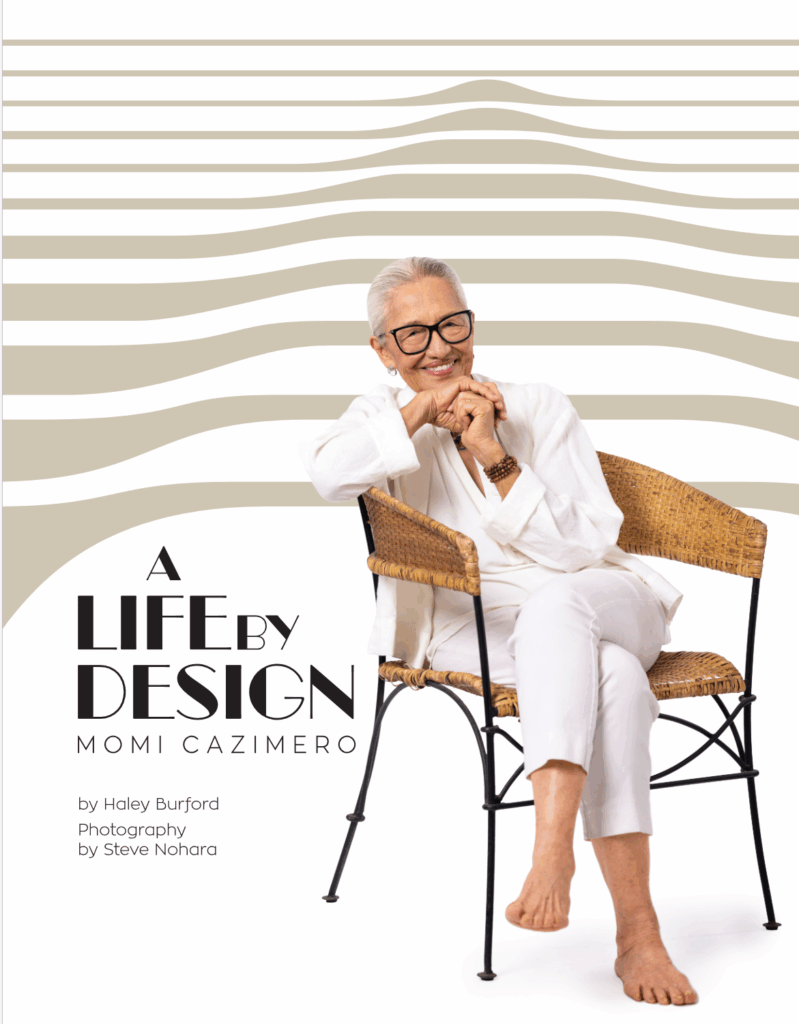

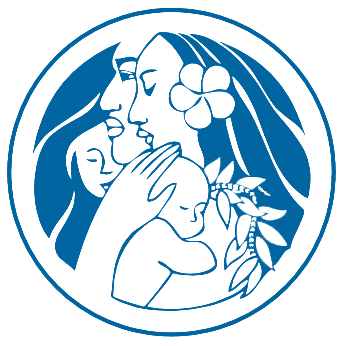

In an open circle, a Hawaiian woman wearing a lei holds a resting baby, her hand protecting the child and inviting the viewer to join in the gift of comfort and healing. Behind the woman are the faces of a man and child, her hair cascading around them. This iconic image—the logo of the Kapi‘olani Medical Center (KMC)—was designed by Momi Cazimero to recognize the hospital’s expansion of services to the entire ‘ohana. Among her many achievements, Momi, now-retired, has created and participated in art exhibitions, served on boards and organizations and is credited with establishing Graphic House, the first woman-owned graphic design firm in Hawai‘i, in 1972. While Momi’s many accomplishments are common knowledge in the graphic arts world, if you ask her, she’ll shine the spotlight not on herself, but on the precious people throughout her life who inspired her to become the woman she is today.

To Elevate Hawai‘i

While working as a graphic designer, Momi’s mission was to “elevate the images and icons of Hawai‘i and Hawaiians,” a feat she achieved through her years of dedication. “It began when I became conscious of the fact that the only thing that had a Hawaiian face on it was the Hawai‘i Visitors Bureau poster,” she says. “The motivation was to bring Hawaiian culture into a contemporary setting, so we’re not always looking for things in a museum.” One significant way in which she accomplished this lies in her designs—for example, for KMC and the Year of the Hawaiian in 2018.

A 1987 issue of Ka Wai Ola O OHA by the Office of Hawaiian Affairs states that the goal of the program called the “Year of the Hawaiian” sought to “Celebrate the Hawaiian, instill pride in being Hawaiian, identify Hawaiian values, lokahi (unity), raise the consciousness and awareness of the Hawaiian core of our society,” enacting an islands-wide series of events and activities focusing on the values, history and culture of the Hawaiian people. “So,” says Momi, “I created something that would represent Papa—Earth Mother—and Wakea—Sky Father. It’s their union that creates the Hawaiian Islands.”

A previous logo depicted a woman literally giving birth to the islands. “In graphic design, we change the literal to the conceptual.” Momi’s iconic design instead alludes to the vast, intricate layers of Hawaiian history and culture, the formation of the islands, and the unity of Papa and Wakea—all with graceful simplicity.

The logo for KMC also reflects the shift from literal to conceptual. Upon explaining her thinking behind the design, Momi emphasizes the hand in the circle. “It’s what you hold—what you give—it’s all associated with the hand. To me, the hand could not break the circle because it brings the viewer in.”

As a graphic designer, Momi stresses the importance of communicating everything in a design: “You must capture who and what it represents—graphic design interprets reality into an image.”

Loving One’s Life

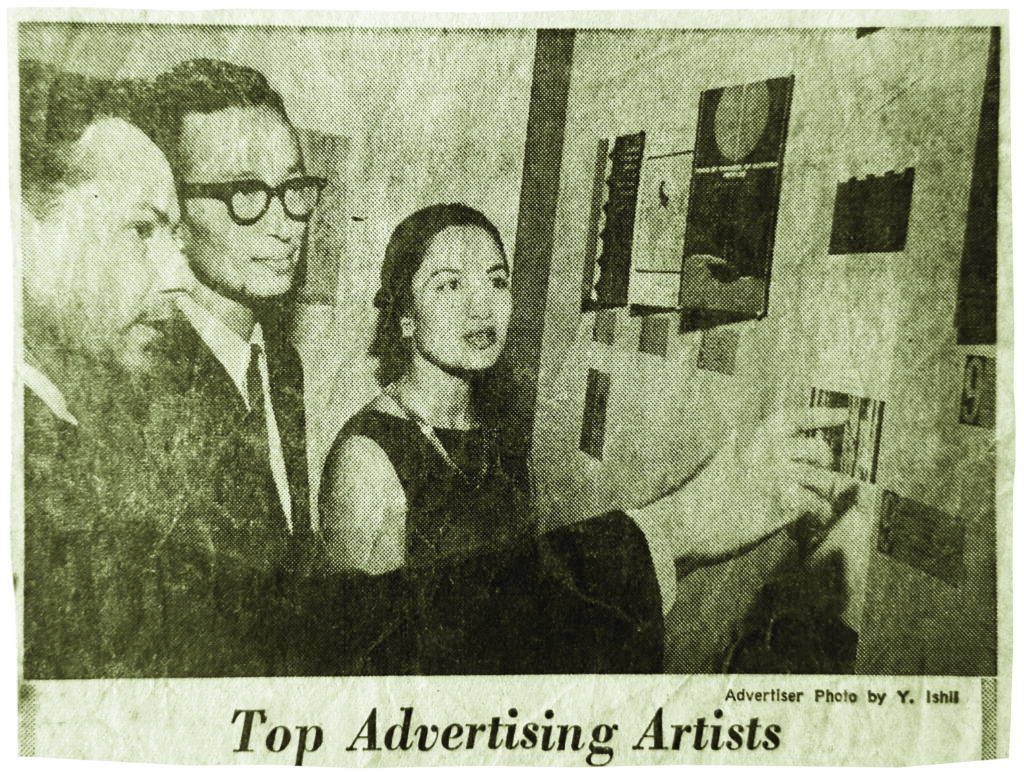

For nine years, Momi worked with Tom Lee of Tom Lee Design, who actually launched graphic design as a business in Hawai‘i. “He and I were responsible for starting and fortifying an organization that advocated for graphic designers. We wanted to create art exhibits to elevate the people’s consciousness of graphic design and the way you do that is by doing something publicly.”

After Tom’s passing and Momi had her own business, she remembers when a group of artists got together and decided to make the showings “more Hawai‘i.” They were going to have an award and name it the Pele Award.

“If you know anything about the Big Island, you know how we feel about Pele,” she says. Momi suggested they change the name, but the group was adamant simply because “‘it was easier to say.’ They were taking the name of a Hawaiian goddess who represents volcanology. They still had to respect the Hawaiian culture. But they went ahead and did it, and I boycotted them.” Momi’s steadfastness affixes her as a figure of Hawaiian pride, leadership and intelligence.

When Tom died of cancer, the Cancer Society called Momi and asked if she could create an exhibit at Ala Moana Center. “So I did. The theme that a friend of mine came up with was ‘Love Your Life.’ I designed the logo and talked to different artists to illustrate their love of life in a pictorial image.” In remembering her dear mentor, Momi also realized something about herself through this exhibit: she wasn’t done yet. “I said to myself, ‘I know what I’m going to do to keep from disappearing. I’m going to do community service.’” Through serving on various boards, committees and organizations, she maintained her public presence, honoring those who came before her and working for those who will come after.

These days, 92-year-old Momi is retired, but still keeps busy with her own creative projects, and recalls her career and loved ones fondly in telling her story. “This morning, I was watching something on TV about The Joy Luck Club,” she says, “and they were talking about how important it is to interpret their culture. The way to lift people up is to give them an opportunity to identify with success. As a Hawaiian, this matters to me because there was an absence of things Hawaiian. Every culture thrives on its understanding and appreciation and relationship to itself. That’s where understanding comes from.” With words from the heart about her creative vision, and the love she has for her art and beloved people throughout her life, Momi Cazimero has paved the way for herself and the many she undoubtedly has inspired to be their best selves.

With all of these acclamations, commendations and encouragement cutting a path to the vanguard, she takes us on a journey down memory lane—back to where it all began.

If You Like, You Can

Momi grew up in rural Pepe‘ekeo on Hawai‘i Island with her grandparents. She was very close with her grandfather, especially. “He was so very positive and supportive, and he spoiled me.” She recalls going to work with him sometimes when he was a highway overseer and remembers fondly when, as she was falling asleep on drives home, he would purposely drive over a certain bump near her favorite bakery to sneakily wake her up— “Tūtū Man, stop!”—so she could ask him to get a slice of her favorite coconut pie. “’Til today, I love it,” she says, “And he did it on purpose all the time. That’s the kind of relationship we had.”

After her grandfather passed away, Momi moved in with her mother, father and siblings per the advice of her Aunty Esther. Instead of the happy, warm days with her grandfather, Momi went to a home environment where she was made to think less of herself because she was a girl. “You can imagine, when I moved into that home, having been raised as the baby,” Momi adds, “how I felt. Before, I even fell asleep on my grandfather.” Laughing, she says, “Okay, I must tell you. He would put me to sleep, and he was a big man. Naturally, when he would put me to sleep, I would roll over on the bed into his side and my head was buried under his arm. My grandmother, I was told, would tear up when she carried me, because my head smelled like his armpit. I was constantly at his side and loved being with him.” When her home environment felt oppressive and she felt hopeless, Momi often turned to memories of her grandfather to keep her going.

The words that Momi’s grandfather spoke to her have maintained their impact many years later. As she grew up speaking pidgin, she mentions how saying “I like” meant “I want.” She says, “It almost suggested that it was something I wanted to do. And whenever it implied that, he would always say, ‘If you like, you can.’ Think of that—the encouragement of it.” Later, when he had already passed and Momi was attending Kamehameha Schools, she still felt his presence. “When I was having a stressful time, I would sit on the edge of my bed and say, ‘Tūtū Man, come get me.’ I always leaned on him. When he didn’t come, I would say to myself, ‘If it was really bad, he would come for me.’ This carried me through everything.” In her senior year of high school, she had a serious discussion with herself: “‘You are always depending on your Tūtū Man.’ I wasn’t going to do that anymore, because I had to do it on my own.” The love and motivation Momi’s grandfather shared with her taught her that nothing is impossible, which propelled her to pursue—and achieve—her dream of becoming an educated and resilient woman.

Never Stop at the Minimum

Towards the end of her senior year of high school, Momi had a meeting with the principal at the time, Dr. Frederick, whose mentorship reminded her of her fourth grade art teacher. Momi says that her desire to become an artist came from this teacher, whose words made a difference. “But,” she states, “I was not studious. In my beginning years, I did not want to go to school, because going to school meant walking miles, barefoot on a stony road. But, it led me to where I am today.”

In the fourth grade, one of her assignments for art class was to draw “the most unusual thing.” One day, on her way to Japanese school, Momi saw an oddly shaped hibiscus plant. “I always looked at that with fascination, because it was so different. That was my subject.” When the teacher was reviewing the classes’ projects, she said that she was saving Momi’s for last. “I thought I was going to be insulted,” Momi adds, “I held my breath.” She finally reached Momi’s piece and her teacher said, “Momi drew this hibiscus and it’s nice. But she did not stop at the minimum.”

After class, when she went to pick up her assignment, Momi’s teacher drew her aside and told her things that Momi carries in her heart to this day: “‘You’re a very good artist. I respect the fact that you had the initiative to do as much as you did. ʻNever stop at the minimum.’ That became a statement that I live with for the rest of my life. In the time that she’s giving me this confidence, what I’m resting on is what my grandfather always said, ‘If you like, you can.’ Here was a teacher who gave me something else to aspire to.” Momi makes note of the fact that these are words that carried her through very bitter years in her upbringing. “The reason I say what pulled me through is because of the things I faced along the way.” With the beautiful and profound statements that these key figures in her life gave to her, it becomes evident how Momi turned the adversity she dealt with into a force that made her unstoppable.

I Wanted You to Grow

Looking back to her childhood, Momi reminisces on her relationship with her Aunty Esther. She mentions how, during the time she was living with her parents, she figured out that the reason her aunt did not face the treatment Momi received was because she had a profession and a college education. At this point, Momi adds, “You know where this story is going already,” referring to this realization being integral to her wanting to create a career for herself. Going against her father’s limiting views of women as bound to the home, Momi decided to work hard and pay for her own schooling. “I’m determined,” she says, and she knew that because she went against her father that she could never go back home —“So, I had to be like Aunty Esther. I had to get a college education.”

Her Aunty Esther was the person who encouraged Momi to take the test to get into Kamehameha Schools, which she passed. Though this was a cause for celebration, it only brought strife to her parents, specifically her father. He insulted her intelligence and dismissed her acceptance into the school, asserting that he wasn’t going to contribute a penny to her education. So, Momi, with the support of her mother and aunt, applied and earned a working scholarship and worked her way through school. After successfully completing her high school education at Kamehameha Schools, Momi spent a brief time in college on the path to teaching art, but decided she didn’t want to do that. “That gets to be a long story, but I’m going to cut to the chase. I wanted to do art, not teach art.” So, she transferred to learning the arts at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. “My mother was distraught. ‘You know, artists starve.’ That’s all she could say to me. She talked to my aunt, who never ever changed my mind. If anybody could have, she could have. But she didn’t say a word to me.” Momi is who she is today because her aunt believed in her.

Years later, Momi found out that her aunt felt responsible for the mistreatment she received in her youth because she is the one who recommended that Momi be raised with her siblings. Like with her grandfather, she and her aunt were very close: “This aunt was also like my surrogate mom. She helped to raise me. When I was in seventh grade, going through college or in my marriage, she was the one I consulted all the time.” The pair were so close that her aunt’s son, Momi’s cousin, even asked if Momi was his older sister. As her aunt got older, she was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. Following the diagnosis, Momi found that her Aunty Esther had become more forthcoming. “She was a typical teacher—always said the right thing, always did the right thing, but here she was. The things she said ranged from funny to serious.” Significantly, one day, Momi was visiting her Aunty Esther and she asked if she was the one who decided that Momi should leave her grandparents’ home all those years ago. Her aunt said yes. “I asked, ‘Why?’ and she said, ‘I wanted you to grow up knowing your siblings.’ When she said this, Momi wanted to say something to her aunt, but she felt she couldn’t, because she didn’t want to cry in front of her. “I felt I had to be strong, but I should have told her what a blessing it was that she made that decision, because I’m sure it haunted her.”

For someone who endured such hardship in her home life to say that it was instead a blessing shows the depths of Momi’s maturity and grace throughout her life, as well as the love and appreciation she feels for her aunt. “I love my Aunty Esther because of who she was and what she was to me. I always wanted to be like her—she motivated me to go to college.”

Never Let the Least of Them Diminish the Best in You

Momi had to work her way through college, too, with a part-time job at Sears. In her senior year of university, she began working for a Swedish artist. “One of the things she loved to do was entertain people in different art fields. My job was to clean up,” says Momi, “and I was never a good cook, so I served food, waited on tables and cleaned the house.”

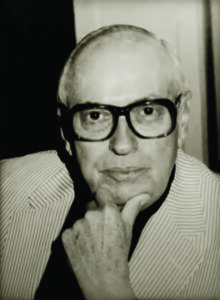

One night, the artist says to Momi, “I want you to join us for dinner. I have a professor; his name is Kenneth Kingery. He’ll be joining us tonight and I think you’re going to enjoy him.” “Did I ever!” After that dinner, Professor Kingery invited Momi to his office and the teacher-student pair grew close from there. He is the

person who introduced Momi to the world of graphic design and, Momi adds, “how it was changing the landscape of commercial art.”

Professor Kenneth Kingery made

an indelible impression on Momi

Cazimero, a budding designer.

At the time, there was an ongoing transition from commercial art to graphic art, where instead of the artist being responsible for only an art piece for a design, graphic artists had to take into account typesets, fonts and colors in addition to being responsible for the art or logo.

Momi relays a story very significant to her development as a budding graphic artist and as a person that took place in her senior year of college. Professor Kingery had assigned her as the school yearbook editor, so she had to design and work with the production crew who printed the yearbook. “That year, I chose to use Chinese calligraphy in the design. I had created all these different designs and colors, and took the bus to discuss what I would be needing. One day, I get there, and the manager looks at it, and he takes it to a light table. He slaps the table, hollers and—this man had the loudest voice you ever heard—calls the other guys over. Those days, only men worked in a print shop.” Momi remembers how all the men gathered around the light table and ridiculed her and her work, laughing all

the while. “‘Look at this thing she brings me,’ he said. I wanted to dig a hole in the concrete and go through it. My heart was just torn. I went to college to develop a profession so that I would have a respectful position, but now I was thinking that

I didn’t want to be a graphic designer.”

Momi remained courteous in the moment and on the bus ride back to Professor Kingery’s office, but when she arrived, he could tell something was wrong. As soon as he asked, Momi burst into tears and told him all that had happened at the print

shop. All Professor Kingery said at that moment was, “You come with me right now.” They drove back to the print shop. “This man spoke in a quiet tone; he was very reserved,” Momi recalls. But, once they arrived, the professor pointed to the manager and said he needed to talk with all of them. Momi remembers verbatim what he said to the men at the light table: “She’s a student at the University of Hawai‘i. You’re grown men, supposedly with a profession. But I don’t think you demonstrated that—not to this student.”

On their way out, he spoke directly to the manager in her defense: “One day, she will amount to more than you ever will.” This moment set a benchmark for Momi. “I was not a confident person, but I had enough people giving me some backbone; my grandfather, for example. Professor Kingery told this man, who was a plant manager, that I would amount to more. You don’t think I had to live up to that? On the way back to the car, he said to me, ‘Never let the least of them diminish the best in you.’ That stays with me—it comforts me and drives me. Every single one of these markers in my life, they both comfort and they drive. And that’s how I got to where I am today.”

Amy Tan, renowned author of The Joy Luck Club, writes, “We dream to give ourselves hope. To stop dreaming—well, that’s like saying you can never change your fate.” Through times when hope was almost lost, Momi designed her fate, never forgetting the people who encouraged her to dream. Momi and her story remind us to choose to love and dream, time and time again.

Leave a Reply